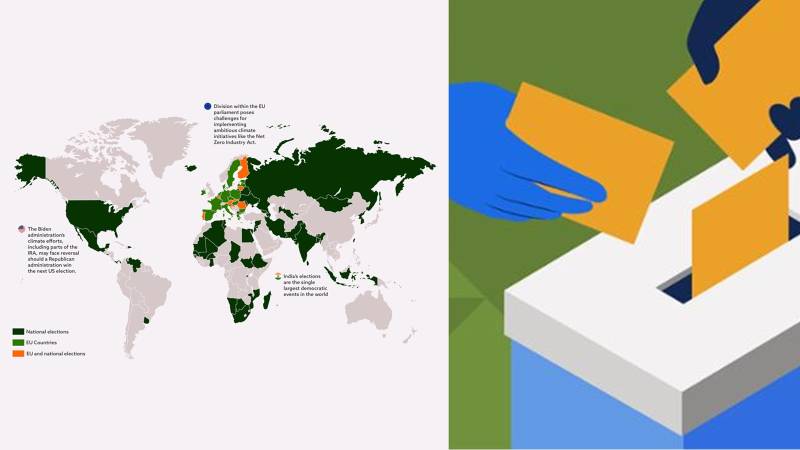

"Short" is, of course, a relative term – because how can you summarise as many as nine different choices in a few words? Not to mention, of course, the Indian elections and the upcoming US elections. When the economic system that has prevailed in the world for 40 years is wavering, it leads to the destabilisation of the political scene. The best expression of the economic crisis is that as many as 27% of Americans – residents of the most powerful country on Earth - skip a meal everyday due to inflation.

Elections were held in South Africa at the end of May. After 30 years in power, the African National Congress (ANC) lost its majority in parliament. President Cyril Ramaphosa nevertheless remained in power. He formed a coalition with the right-wing Democratic Alliance (DA), representing the interests of whites (basically a party of white supremacists, Afrikaners), as well as several minor right-wing parties such as the nationalist Zulu party – Inkatha Freedom Party. It is true that the coalition partners did not receive very important ministries. DA leader John Steenhuisen became agriculture minister. This is a symbolic move that has been criticised, because activists involved in the fight against apartheid rightly argue that the white minority still controls the best land in South Africa.

On 02 June, elections took place in Mexico. There, the party and the candidate of incumbent leftist president Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the elections. This is significant because, first of all, his successor and president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum will become the first woman in Mexican history to hold that highest office. The Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (Morena) party and its coalition partners won a constitutional majority in parliament. Additionally, Sheinbaum defeated the combined neoliberal parties which ruled Mexico for almost 60 years) and the PRI (which ruled in the early 21st century). These parties have always been officially "enemies" (although both represent the interests of the Mexican bourgeoisie) and this time they fielded a common candidate. Despite this, Morena's candidate won the highest percentage of votes in Mexican history. Of course, despite such a strong mandate, this will not be an easy term for Sheinbaum. It faces rising gang violence, climate change, transportation, and economic problems.

In June, elections were also held in Mongolia, which extended the rule of the Mongolian People's Party since 2016. However, the party gained less support than polls predicted. This is due to Mongolia's economic problems and the ubiquitous corruption that has prevailed since the MPP returned to power. Unfortunately, right-wing parties are benefiting from this – the traditional opposition to the MPP, ie the neoliberal Democratic Party, but a new party has also appeared – Hun. I say unfortunately because the popularity of such parties is terribly disturbing. This is a group similar to Macron's movement in France, Future Forward in Thailand, Syed Saddiq's party in Malaysia or Rabi Lamichhane's party in Nepal. These are parties that present themselves as "defending the interests of young people" or "opposing the elites." But in reality, these are parties based on charismatic millionaire leaders who represent a liberal upper middle class enchanted by Western societies. So it is undoubtedly a very dangerous political trend when such forces gain support because under the guise of being "cool," they represent brutal neoliberalism and corporatism.

The elections in Belgium and Bulgaria deepened the political crises there. In Bulgaria, these were the sixth elections in the last 3 years! Despite these elections, it was not possible to form a government. In Belgium, elections are bringing instability. 5 years ago, the formation of a new government took over a year and it will probably look like this now.

There were also elections in Iran, which were organised after the death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a plane crash. Raisi was a representative of the so-called "principalist" faction in the Iranian power structure. After his death, many pro-Iran commentators in the world's media wrote that he was a "universally loved leader." One could therefore get the impression that his faction would win the presidential elections without any problems. Despite everything, the conservative candidates Jalili and Ghalibaf (one an autarkic conservative and the other a fanatical neoliberal conservative) lost quite badly. The only candidate of the so-called "reformists" won: Masud Pezeshkian. Pezeshkian is a representative of a minority – he is half Kurd and half Azeri. He represents a relatively "social democratic" economic policy and during the campaign called for liberalisation in social issues (including reform of the law regarding the requirement to wear hijabs).

The elections to the European Parliament ended on 09 June. They did not fundamentally change the balance of power in the European Union. The Greens and Liberals, as well as Social Democrats, lost support. Meanwhile, far-right forces gained. Despite this, the centre-right European People's Party, Social Democrats, Liberals and Greens maintained a stable majority in the European Parliament. However, the fact that the EPP won one more seat than five years ago meant that it demanded more top positions in the EU (they also wanted the position of EU Council President). As a result, EU leaders were not elected for the next 2.5 years at the first meeting of EU leaders in mid-June.

It is worth mentioning here that the most important positions in the EU are: the President of the European Council (the person who convenes meetings of the leaders of EU countries – the most important decision-making body), the President of the European Commission (ie something like the "EU government," which gives direction to EU policy), the head of EU diplomacy (ie the “foreign minister” of the EU) and the President of the European Parliament. Ultimately, the division of positions (made behind closed doors by EU country leaders) was as follows:

Ursula von der Leyen, an EPP member from Germany, will become President of the Commission for the next term. Over the last 5 years, she has proven to be a basically faithful executor of Washington DC's will in the EU, which it proved during its approach to the conflict in Ukraine.

Antonio Costa, former Prime Minister of Portugal, representative of the European "social democrats," will head the European Council. Costa resigned last year after huge corrupt scandal in his government.

The head of EU diplomacy will be the Prime Minister of Estonia, Kaja Kallas, who is a representative of the Liberals. She became known for her profile as a fanatical supporter of NATO and her unbridled Russophobia. Her government, for example, has virtually banned Russian citizens from entering Estonia. The choice of Kallas is very interesting in the context of geopolitical changes in the world. She represents probably the most Russophobic faction of all European elites. Meanwhile, everything indicates that Donald Trump will win the US elections. Both he and his vice presidential candidate, JD Vance, show no desire to continue supporting Ukraine. This means that in 2025 the EU may stand in opposition to the head of NATO, the USA, regarding Ukraine.

EPP representative Roberta Metsola from Malta was once again selected as the President of the European Parliament.

There is one more thing worth noting about this election. As a result of the elections, far-right and populist forces created a new faction – Patriots for Europe. They became the third largest faction in the European Parliament. They include among others Le Pen's National Rally, Orban's Fidesz (which was part of the EPP), the fascist FPO from Austria, former Czech Prime Minister Babis' ANO (which was previously in the liberal faction) and Wilders' Dutch PVV.

These elections, as a rule, do not have a major impact on the policies of individual European countries. All important decisions for the EU are made at meetings of the European Council, ie by the presidents or prime ministers of EU countries, and not by the directly elected European Parliament. Moreover, European Parliament elections are the least popular of all elections. In the Czech Republic, for example, turnout was just 35%.

There is no revolutionary force in the world that could overcome systemic stagnation and an unsustainable status quo

Nevertheless, France was quite significantly affected by these elections. As a result of the fact that the far-right, Islamophobic, and xenophobic party of Marine Le Pen won over 30%, French President Emanuel Macron dissolved the parliament. France was therefore forced to hold parliamentary elections. In the first round, which took place at the end of June, the National Rally won as much as 33%. In the French system, candidates who received at least 12.5% in the first round advance to the second round. This resulted in a three-way election in many constituencies between the candidate of NR, Macron's party, and the candidate of the Nouveau Front Populaire (NPF, which is a coalition of left-wing parties from the Greens to the Communists). Before the second round, Macron's liberals made a pact with the NFP that they would withdraw their candidates from the three-way races and only the stronger one would be left against Le Pen's candidate. This had the intended effect. Although the National Rally received as much as 37% of the votes, they were only third in the distribution of seats, retaining only 142 seats. The left-wing NFP won the elections, winning 180 seats although only 25% of the votes. Macron's liberals received 24% of the votes and as many as 159 seats.

One may ask why Macron took such a risk and called the elections after the decisive victory of the far right in the elections to the European Parliament. Since 2022, when Macron won his second presidential term, he has lost his majority in parliament. His party did not have a stable majority, and the president himself often had to rule by decree because the parliament rejected his draft laws. He therefore concluded that the result of the European elections would mobilise the French who were terrified of Le Pen's xenophobia. He wasn't wrong. The turnout was 67%, which was the highest in France since 1997. Of course, his party lost in these elections, but the "anti-Le Pen" narrative won.

Therefore, I do not agree with the analysis of Professor Prabhat Patnaik, who in his article Halting the March of Fascism in Europe optimistically states that fascism was defeated in France by the left-wing front. First of all, the left did not ‘win.’ The left is only the largest coalition in the French parliament. They are 109 seats short of a majority. Secondly, in the French system, the president has real power: the parliament can basically only obstruct him from governing. Thirdly, the left became the largest force in the French parliament only thanks to its coalition with Macron, whose government it criticised throughout the campaign. In my opinion, the French elections only showed that French society is still afraid of the prospect of Le Pen coming to power, and not that they want a left-wing government. Of course, the NFP program, which is described quite well by Patnaik in another article is not a bad programme, but in my opinion it is not a success of the left, but a negative vote towards Le Pen.

A similar situation occurred in the situation of the last country that I would like to discuss today, Great Britain. There, at the end of May, Rishi Sunak, in a shocking decision, announced early elections. This is shocking because the Conservatives, who have been in power for 14 years, have been losing support in polls for over two years. So it was obvious that they would lose this election. I can't answer the question why Sunak called the election now and not in December when it should have been held. Sometimes the simplest solution seems to be the best - I guess the Tories were just tired of 14 years of constant scandals. Additionally, Sunak announced the dissolution of parliament – in the rain, being all wet because he did not take an umbrella to the press conference. There could not have been a more ‘British’ and symbolic end for the Conservatives.

The Labour Party won the elections on 04 June, returning to power after 14 years. They won 411 seats – the most since 2001. But was it a success for Labour? Not completely.

This is a success of the electoral system, which turned out to be extremely unfair. Labour won only 34% of the votes. This is the lowest share won by any party securing an overall majority in Parliament, however small – let alone a party winning a landslide in seats. The Conservative Party won 23% of the votes and only 121 seats: the lowest number in history. The combined Labour and Conservative vote share was 57.4%, the lowest since the 1918 general election.

Smaller parties took a record 42.6% of the vote in the election, in part due to anti-Conservative tactical voting. The Liberal Democrats, led by Ed Davey, made the most significant gains by winning a total of 72 seats. This was the party's best-ever result and made it the third-largest party in the Commons, a status it had previously held but lost at the 2015 general election. The fascist party Reform UK achieved the third-highest vote share and won five seats, and the Green Party of England and Wales won four seats. Both parties achieved their best parliamentary results in history, winning more than one seat for the first time.

Labour lost a number of former strongholds to independent candidates campaigning on pro-Gaza platforms. The shadow minister Jonathan Ashworth lost his Leicester South seat, where he previously had a majority of more than 22,000. Wes Streeting, who was one of Labour’s most high-profile figures during the campaign and who is now the health secretary, saw his majority in Ilford North, in London, reduced from more than 9,000 to just 528.

Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn continues to represent the constituency he has held since 1983. Corbyn won Islington North as an independent candidate, having being blocked from being a Labour candidate in March 2023 by Starmer. It must be noted that in the 2024 elections, the Labour Party got half a million less votes than in 2019 under Corbyn, when it achieved the worst result in history in terms of seats.

UK voters were tired of the disastrous Conservative rule and often voted for Reform UK. As a result, RUK was third in many constituencies. For example: In South West Norfolk, Liz Truss was defeated by Labour’s Terry Jermy. Socialism sweeps the Fens? Not exactly. Jeremy won just 26.7% of the vote. But in a crowded field, first-past-the-post does odd things. Truss, with 25.3%, was followed closely by Reform’s Toby McKenzie, on 22.5%. Had just one in ten Reform voters backed Truss, she would have held her seat.

The YouGov poll showed that these elections were not a success for Keir Starmer, who is Labour’s leader and the new Prime Minister of Great Britain, as naive social liberals around the world would like to claim. In this poll, YouGov asked Labour voters why they would vote for the party on 4 June. As many as 48% answered "to get rid of the Tories," 13% "the country needs change" and only 5% "I agree with their policy". This means that the ‘social’ programme did not win. And no wonder. Labour had a social agenda under Corbyn. Nowadays they are probably best characterised as "Tories dressed in red". Labour has pledged to stick to conservative tax and spending plans (another similarity to Tony Blair's approach in opposition) and has recently come under fire for backtracking on its flagship £28 billion green energy investment pledge.

To sum up, June and early July were very hot months: not only as a result of climate change, but also political change. On the horizon, of course, are the US elections, where the campaign and constant surprising moments may change their course.

As such, there is no revolutionary force in the world that could overcome systemic stagnation and an unsustainable status quo. In fact, as the EU and UK elections have shown, a change of power in bourgeois democracies is just a repainting of an old chair, not a real change.

However, an awakening of working people is emerging around the world. It can be seen, for example, in the protests in Kenya against the scandalous budget bill. When such acts of anger of oppressed people are organised by a revolutionary party, they will become a political force capable of change.