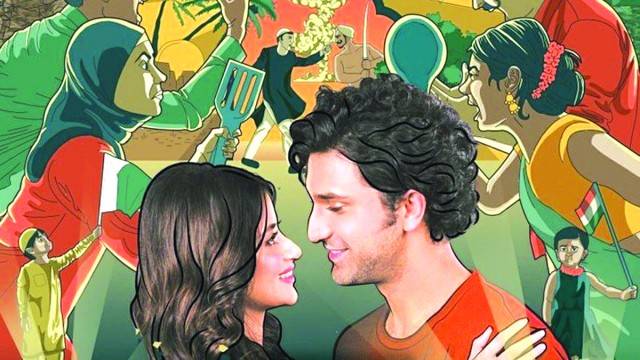

Recently, Umera Ahmed, the writer of a serial called Dhoop ke Dewar has gotten much flak for the teaser of the serial. The serial, which will be aired on an Indian channel, Zee5, is a love story between a Pakistani girl and an Indian boy and through that framework argues for peace between the two countries.

As a private citizen, Ahmed is under no obligation to write a script that must present Pakistan’s view. In her defence, she has already said that the serial was not written for Zee5, but for a Pakistani content company Group M. She says that she had signed a contract with the group for Dhoop ke Dewar and three other stories in 2018. Later, Group M decided to sell this serial to an ‘international platform,’ including Netflix and some others. They cut a deal with Zee5 after the latter showed interest in airing it. She also said that many other Pakistani channels have contracts with Zee and Star Plus and they have raked it in. There’s nothing wrong with that because the revenue comes to Pakistan.

This too cannot be faulted. As a writer she is free to be commercially conscious and write something that would sell well and therefore be pleasantly remunerative. It is the same with Group M. It is not a charity and is in the business of producing content that can make money and a lot of it, which is why it likely suggested a certain line for this serial which it could then sell to a platform outside Pakistan.

Further, anyone calling for curbing Ahmed’s right to write what she wants or to fatten her coffers will be making an argument in favour of state scrutiny and regulations that must best be avoided. Having said that, other private citizens have the right to criticise Ahmed’s treatment of the theme and/or point to its mawkish approach to issues of war and peace by relying on a device (adversaries in love) that has been the rather stale staple of Bollywood.

Let us, therefore, talk about some facts to see why Ahmed has been criticised and why she needed to defend herself. It is a fact that her serial fits the Indian narrative on all counts and what’s absolutely wonderful from Zee5’s (and India’s) perspective is that it is done by Pakistanis! If you can get the ‘other’ to voice your narrative, you have already won.

Ahmed has created a serial whose entire language, symbolism and narrative dovetails with India’s. Her ‘desire’ for peace has no place for Kashmir’s plight or voice

In her defence, she also said that when she began working on the concept in 2019, she had a meeting with Inter-Services Public Relations (we don’t know who represented ISPR in that meeting). “They” evaluated, approved and supported the project and assured Ahmed that they too wanted peace between Pakistan and India and to put an end to the conflict at the Line of Control.

To the best of my knowledge, ISPR has remained silent on this so far. While Ahmed is a private citizen, ISPR is not, so let’s deconstruct it. Given the criticism, it is clear that Ahmed thinks that by pointing to ISPR’s approval, she can shield herself and her work from criticism, presumably because the ISPR is the bell-wether of national interest. The bad news is that it is not. A script approved by the ISPR does not automatically make it better. But I am thankful to Ahmed for the information that the ISPR, in addition to being the public relations arm of the army (inter-services is just a formality) also performs the dual function of vetting and censoring films and serials. Since I am not aware of any legal provision that allows the ISPR to do that, I think it is safe to assume that this function has been appropriated arbitrarily and in the ‘larger interest’ of Pakistan.

Except, in the case of Ahmed’s script, it neither serves Pakistan’s interest nor is it in line with Pakistan’s position with reference to India’s occupation of Jammu and Kashmir and a host of other disputes. If, as she says in her defence, the ISPR told her that ‘they’ (ISPR/army) also want peace and quiet at the LoC, then the best way would be to legalise the line into international border — that, of course, would mean Pakistan’s acceptance of India’s occupation of J&K. Is that the line now? This may not be an issue of concern for Ahmed as a writer but it should be for the ISPR, especially if it chose to put its imprimatur on the script.

If that is not the line, and if we also reject India’s illegal annexation of J&K, then we should be prepared for conflict in order to deter it, not show a desire for peace through mushy love stories and branding Kashmiri freedom fighters ‘terrorists’.

In her defence, Ahmed also says that there’s nothing wrong in being a supporter and promoter of Aman ki Asha. I agree with that. However, as noted earlier, as a private citizen I am also free to inform her that while having a great eye for what will sell in India and internationally, she has ignored that (a) India wants peace on India’s terms; (b) it continues to suppress and kill Kashmiris; (c) it wants to be the regional hegemon (it’s a structural problem); (d) the best guarantee for peace is not peace but the power to deter — strategy is paradoxical: si vis pacem para bellum, not si vis pacem para pacem. These are all facts.

Similarly, it is a fact that Ahmed has created a serial whose entire language, symbolism and narrative dovetails with India’s. Her ‘desire’ for peace has no place for Kashmir’s plight or voice. In doing that, she does not realise — or maybe as a writer she clearly does — that making meaning is not just a cognitive exercise. There’s an impressive corpus of literature on the relationship between language and power and how language is used as a means to construct power and maintain it.

As linguist Robin Lakoff says in The Language War, “…since so much of our cognitive capacity is achieved via language, control of language—the determination of what words mean, who can use what forms of language to what effects in which settings—is power. Hence the struggles I am discussing…are not tussles over ‘mere words,’ or ‘just semantics’—they are battles.”

As I said, Ahmed, as a writer, should know this. Take the word ‘terrorism’. It is supposed to evoke a response, a negative one. But its placement in the language is more than that. It is about setting a context and wielding power to delegitimize a struggle and to legitimate violence. When you brand Kashmiris ‘terrorists’, which is what India has consistently sought to do and which Ahmed’s serial also does — going by the teaser — you justify statist violence against them and delegitimise their rights as an occupied people. The right to armed struggle for “liberation from colonial and foreign domination and foreign occupation” is enshrined in UN General Assembly resolutions. These are facts. By presenting India’s narrative on Kashmir, Ahmed’s serial gravely wrongs the Kashmiris.

There’s an Israeli series on Netflix, Fauda (Chaos). Watching it is instructive in how the Palestinian characters are depicted as flat and one-dimensional ‘terrorists’ while members of the Israeli covert operations unit are shown as rounded characters, soldiers, complex and multi-dimensional. I mention this because, and this would perhaps be instructive for Ahmed’s approach to peace, India Today reported on November 8, 2019 that the series “is all set to get an Indian remake” and “the Indian adaptation version…will highlight the complicated relationship between India and Pakistan.” Those who have watched Fauda can figure out the narrative the Indian remake would push.

The criticism really is with reference not only to Ahmed’s saccharine approach to peace but more so about either ignoring or distorting facts with reference to the complexity that informs India-Pakistan conflict, Kashmir and Kashmiri aspirations.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider