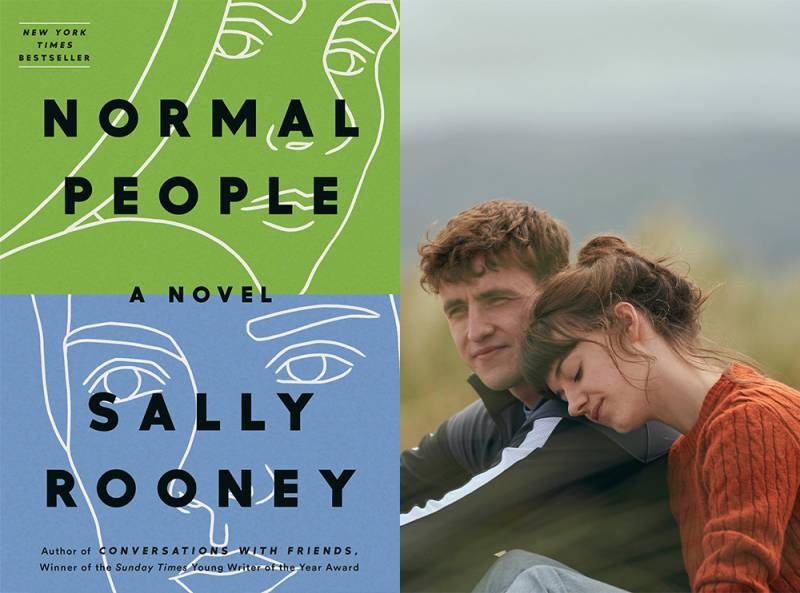

I was first struck by the popularity of Rooney’s ‘Normal People’ when a close friend sent me a snippet of Marianne Sheridan, the eccentric heroine of the show. She lies in bed beside Connell Waldron, her childhood love, as their trajectories weave in and out of each other’s journey in life. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me. Don’t know why I can’t make people love me. I think there was something wrong with me when I was born.” She labelled it with a, “I wonder why this really reminded me of you; I haven’t watched the show yet, but I might soon.” I was perplexed– how had someone managed to put the absolute core of my dilemma into words? The idea of a woman suffering, ostracized from society because of her genius and talent, forced to seek love in violence resonated with me at a core level. To add to that, I had seen too many narratives take female suffering and screen it as martyrdom or a vessel to romance. I had spent so many nights sitting there, musing about how absurd love was, how it had left me ostracized and fearful. I decided to give the 12-episode series by directed by Lenny Abrahamson and Hettie Macdonald a watch.

Let’s just say, as someone who truly struggles to finish a show in a single sitting, I ended up pulling two all-nighters to finish it in 48 hours. I think the most decisive factor for me being completely enamored with this show was the fact that it was a romance, yes, but also an exploration of humanity– I saw the characters on screen grow from being gangly, awkward high school teenagers with very little sense of direction, pulled apart by this inherent meanness your peers that age have, to finding themselves and coming to terms with their fears and enigmas and becoming better human beings. With that, it incorporated discourse on class inequality, childhood abuse and narcissistic parenting, the status quo represented to you in university, especially in the liberal arts, where everyone tries to one-up the other by being egregiously pretentious, the dynamics of sex and sexuality that often befall vulnerable women where they are put in situations that are abusive but are presented as moments of passion, and mental health struggles. The fact that all of this naturally fell into the story-telling and did not come off as a desperate attempt at virtue signaling for brownie points made me all the more enamored.

I can frankly talk about the love Marianne and Connell shared for days– they were first and foremost friends, and flawed at that. They made the mistakes perhaps all of us did when we were grappling with our sense of identity in young adulthood, but they managed to find their way out. They had the utmost respect for one another– at one point, Marianne’s elitist college classmate, which she feels, to an extent shunned by, despite them sharing her wealth and status, questions her: “Is he smart?” She nods, cigarette smoke wafting softly as her bangs brush into her eyes. “He is the smartest person I know.” Connell repeats the same sentiment about Marianne when he is in conversation with a peer. Apart, they still find ways to hold each other with the utmost regard and generosity. Their love is soft, yet passionate– even if everything around them is set on fire, they find the hope of it all in one another. To the basking flames of their life, they both are each other’s gentle ocean breeze, always gravitating towards one another. “It’s not like this with other people,” Marianne whispers to Connell in one of their moments of passion (there are many; and I appreciate the screenwriters for making them ones that add to the plot and the nudity is not present for the sake of it, rather to build the plot). The last episode left me sobbing at 2 a.m. and sometimes when I want to inflict a tumultuous emotional burden on myself, I rewatch it to let myself have a good cry. It still continues to be one of my favorite shows, and the very rare ones that end up doing justice to the book.

It was only after I was done with the show that I decided I would like to read the book– mostly because someone who had once given me too many opinions on everything told me that it was a joke. “I loathed it, absolutely,” he told me, “I hate how she writes. Not worth reading.” And I did see many people criticize her lack of speech marks in her dialogue, which I definitely thought would be irksome for me; however, months after this conversation I think I had a mild awakening. I needed to form my own opinions rather than depend on others to tell me what to do. At one point early in the show, Marianne says: “I object to every thought or action or feeling of mine being policed like we're in some authoritarian fantasy.” I decided to take her words at face value and read the book for myself. It definitely added to my perception rather than take away from it.

The key difference was how much I enjoyed Rooney’s dry, witty humor and observation. It’s almost wry how simple her writing is, yet how much it manages to capture in that tone– she doesn’t have to be ostentatious to get herself across to the reader. The characters were more fleshed out too; specifically, Marianne’s. If we compare the show with the book, we see that Marianne is demurer and primmer in the show— her awkwardness is not as highlighted as it is in the book. She is almost this sad, misunderstood gamine with her little quirks; they add to her element. She is ostracized but in a way that is still attractive. In the book, she has no reservations about her perceived weirdness, in fact, she revels in it. Connell’s narrative, on the other hand, is always in tandem with the people around him— he cares much more for their opinion of him rather than his opinion on anyone or anything. That is what sets him and Marianne apart in both the book and the show.

It is why she finds it smooth sailing in Trinity College, Dublin, where the educated lots like her for her non-conformational attitude while Connell struggles with his sense of identity in the same place as her; since he always revolved around others. Outside the fishbowl of the small community and the lack of diversity in thought and opinions in his high school, he feels strange, as if suspended in time. It is also what caused his initial qualms with taking a stand for Marianne against his ‘friends’ and their bullying; he is too scared to lose his social respectability, aided by the fact that Marianne is a social stratum above him in the economy, while his mother is a cleaner at her house. This innate fear sketches out his trajectory, as he comes to terms with their differences. “It's not class consciousness exactly, just a deep-seated conviction that the life he's living now isn't quite right for him, that if he were smarter or more sophisticated, he would be leading a different kind of life,” Rooney writes at one point. He always feels a sense of “class betrayal” being inside her house that puts him on edge, and it only deepens at Trinity.

It is what also builds the spark between them– Marianne comes from an abusive household with a brother that constantly berates her and a mother that stands as a silent spectator. The oppressive environment she can’t stand up to at home, she manages to stand up to in school. One thing I did note in contrast to the show versus the book was that in the show, Marianne is less likely to conform to her brother and bolder in her criticism of his treatment of her. Here, she seems fiery when it comes to standing up to all around her, except her family. Her silence implodes in places she can answer back without grievous consequences. This lack of filter is what sets Connell at ease around her; his lack of sense of self and dwindling self-confidence adds to his dilemma with sex; he feels as if voyeurs are always perceiving him. With Marianne, he feels at ease because she is so at ease with not conforming to social customs that it translates into him being at ease too. He feels vulnerable with her because he knows that she is ostracized— no matter what he says to her, she will hold it with deep regard. It is because she is all too familiar with how it is to be exiled, and she can see that he desperately tries to fit in. She offers him the safe space he can’t find externally.

Another layer that adds to Marianne’s character in the book is how you can clearly perceive her as being a giver; emotionally, mentally, and physically. She fears it, and that is why she prefers to give nothing rather than everything. Connell is the first person she gives her all to. Apart from him, it often leads her to be strewn into abusive environments, especially with romantic partners. “There’s always been something inside her that men have wanted to dominate, and their desire for domination can look so much like attraction, even love,” Marianne muses in the later chapters of the book. Juxtapose this with Connell looking at her and saying, “Marianne, I am not a religious person; but I do sometimes think God made you for me,” and you see the stark difference. It tears her apart, yet it is his love and admiration for him over the years that makes her break from conforming with the pattern of abuse her partners replicate. She grows from the angry, ornery young girl who despises the system to someone who mellows out into an adult less full of rage, yet still as opinionated and bright as she was.

Connell struggles with his identity and sense of self in this space away from his comfort zone. He weaves in and out of falling into a state of utter despondence and anxiety, and it is Marianne, even though they are apart, that helps him look for professional help. It is an enriching experience to read and see on-screen struggles with mental health in a manner that does not make it a romanticized version of a nihilistic solitude that propels you towards greatness– it is dark, gritty and hard to deal with. He also grapples with his Literature degree and the complications with the economy– “That’s money, the substance that makes the world real. There’s something so corrupt and sexy about it.” He grows from being a fragmentary young boy to a self-assured young man who is confident in his sense of self.

What makes this journey of two flawed individuals so beautiful is the support they give to each other during this search for their independent personhood. Their teenage narcissism of wanting to be so different and being so absolutely conscious of how they don’t fit in, settles into being at ease with this difference and accepting that there will always be more similarities that they’ll have with the world at large rather than differences. Add to this Rooney’s Marxist perspective on class and wealth, and the fresh breath of technology she laces into the work– without it being jarring, rather, being much more natural– you have a well-written piece of fiction. I like to think we are an epistolary generation; our feelings are communicated over text, just like they were generations ago. The only difference is the time frame these words are delivered. This changes the literary territory we are used to; our online personas creep into literature, our humor and our communication. This is what makes the end so special– we have no clue where it will take our beloved characters, just a note of hope.

I would like to say frankly, that this show and book is one that resonated with me on a level I still can’t shake off. Perhaps that is what makes Rooney’s work so special– she is polemic, and manages to capture our societal norms and modern-day culture in her books, mostly set in the quintessential Irish landscape, with a lucidity many lack. Her characters are sharp, witty, flawed humans who allow us a glimpse into ourselves. Why I found this so heart-wrenching was because ever-giving, chockfull of kindness, Marianne answers the door at the start of the narrative. “Marianne answers the door when Connell rings the bell.” And just like that, towards the end their strings of fate tie in with a, “I’ll be here; you know that.” This was noted by many of the readers as being something that left them sobbing, and frankly I understand it. It’s definitely something you can’t put down once you have started it, and one that lives up to its popularity.

Let’s just say, as someone who truly struggles to finish a show in a single sitting, I ended up pulling two all-nighters to finish it in 48 hours. I think the most decisive factor for me being completely enamored with this show was the fact that it was a romance, yes, but also an exploration of humanity– I saw the characters on screen grow from being gangly, awkward high school teenagers with very little sense of direction, pulled apart by this inherent meanness your peers that age have, to finding themselves and coming to terms with their fears and enigmas and becoming better human beings. With that, it incorporated discourse on class inequality, childhood abuse and narcissistic parenting, the status quo represented to you in university, especially in the liberal arts, where everyone tries to one-up the other by being egregiously pretentious, the dynamics of sex and sexuality that often befall vulnerable women where they are put in situations that are abusive but are presented as moments of passion, and mental health struggles. The fact that all of this naturally fell into the story-telling and did not come off as a desperate attempt at virtue signaling for brownie points made me all the more enamored.

I can frankly talk about the love Marianne and Connell shared for days– they were first and foremost friends, and flawed at that. They made the mistakes perhaps all of us did when we were grappling with our sense of identity in young adulthood, but they managed to find their way out. They had the utmost respect for one another– at one point, Marianne’s elitist college classmate, which she feels, to an extent shunned by, despite them sharing her wealth and status, questions her: “Is he smart?” She nods, cigarette smoke wafting softly as her bangs brush into her eyes. “He is the smartest person I know.” Connell repeats the same sentiment about Marianne when he is in conversation with a peer. Apart, they still find ways to hold each other with the utmost regard and generosity. Their love is soft, yet passionate– even if everything around them is set on fire, they find the hope of it all in one another. To the basking flames of their life, they both are each other’s gentle ocean breeze, always gravitating towards one another. “It’s not like this with other people,” Marianne whispers to Connell in one of their moments of passion (there are many; and I appreciate the screenwriters for making them ones that add to the plot and the nudity is not present for the sake of it, rather to build the plot). The last episode left me sobbing at 2 a.m. and sometimes when I want to inflict a tumultuous emotional burden on myself, I rewatch it to let myself have a good cry. It still continues to be one of my favorite shows, and the very rare ones that end up doing justice to the book.

It was only after I was done with the show that I decided I would like to read the book– mostly because someone who had once given me too many opinions on everything told me that it was a joke. “I loathed it, absolutely,” he told me, “I hate how she writes. Not worth reading.” And I did see many people criticize her lack of speech marks in her dialogue, which I definitely thought would be irksome for me; however, months after this conversation I think I had a mild awakening. I needed to form my own opinions rather than depend on others to tell me what to do. At one point early in the show, Marianne says: “I object to every thought or action or feeling of mine being policed like we're in some authoritarian fantasy.” I decided to take her words at face value and read the book for myself. It definitely added to my perception rather than take away from it.

The key difference was how much I enjoyed Rooney’s dry, witty humor and observation. It’s almost wry how simple her writing is, yet how much it manages to capture in that tone– she doesn’t have to be ostentatious to get herself across to the reader. The characters were more fleshed out too; specifically, Marianne’s. If we compare the show with the book, we see that Marianne is demurer and primmer in the show— her awkwardness is not as highlighted as it is in the book. She is almost this sad, misunderstood gamine with her little quirks; they add to her element. She is ostracized but in a way that is still attractive. In the book, she has no reservations about her perceived weirdness, in fact, she revels in it. Connell’s narrative, on the other hand, is always in tandem with the people around him— he cares much more for their opinion of him rather than his opinion on anyone or anything. That is what sets him and Marianne apart in both the book and the show.

It is why she finds it smooth sailing in Trinity College, Dublin, where the educated lots like her for her non-conformational attitude while Connell struggles with his sense of identity in the same place as her; since he always revolved around others. Outside the fishbowl of the small community and the lack of diversity in thought and opinions in his high school, he feels strange, as if suspended in time. It is also what caused his initial qualms with taking a stand for Marianne against his ‘friends’ and their bullying; he is too scared to lose his social respectability, aided by the fact that Marianne is a social stratum above him in the economy, while his mother is a cleaner at her house. This innate fear sketches out his trajectory, as he comes to terms with their differences. “It's not class consciousness exactly, just a deep-seated conviction that the life he's living now isn't quite right for him, that if he were smarter or more sophisticated, he would be leading a different kind of life,” Rooney writes at one point. He always feels a sense of “class betrayal” being inside her house that puts him on edge, and it only deepens at Trinity.

It is what also builds the spark between them– Marianne comes from an abusive household with a brother that constantly berates her and a mother that stands as a silent spectator. The oppressive environment she can’t stand up to at home, she manages to stand up to in school. One thing I did note in contrast to the show versus the book was that in the show, Marianne is less likely to conform to her brother and bolder in her criticism of his treatment of her. Here, she seems fiery when it comes to standing up to all around her, except her family. Her silence implodes in places she can answer back without grievous consequences. This lack of filter is what sets Connell at ease around her; his lack of sense of self and dwindling self-confidence adds to his dilemma with sex; he feels as if voyeurs are always perceiving him. With Marianne, he feels at ease because she is so at ease with not conforming to social customs that it translates into him being at ease too. He feels vulnerable with her because he knows that she is ostracized— no matter what he says to her, she will hold it with deep regard. It is because she is all too familiar with how it is to be exiled, and she can see that he desperately tries to fit in. She offers him the safe space he can’t find externally.

Another layer that adds to Marianne’s character in the book is how you can clearly perceive her as being a giver; emotionally, mentally, and physically. She fears it, and that is why she prefers to give nothing rather than everything. Connell is the first person she gives her all to. Apart from him, it often leads her to be strewn into abusive environments, especially with romantic partners. “There’s always been something inside her that men have wanted to dominate, and their desire for domination can look so much like attraction, even love,” Marianne muses in the later chapters of the book. Juxtapose this with Connell looking at her and saying, “Marianne, I am not a religious person; but I do sometimes think God made you for me,” and you see the stark difference. It tears her apart, yet it is his love and admiration for him over the years that makes her break from conforming with the pattern of abuse her partners replicate. She grows from the angry, ornery young girl who despises the system to someone who mellows out into an adult less full of rage, yet still as opinionated and bright as she was.

Connell struggles with his identity and sense of self in this space away from his comfort zone. He weaves in and out of falling into a state of utter despondence and anxiety, and it is Marianne, even though they are apart, that helps him look for professional help. It is an enriching experience to read and see on-screen struggles with mental health in a manner that does not make it a romanticized version of a nihilistic solitude that propels you towards greatness– it is dark, gritty and hard to deal with. He also grapples with his Literature degree and the complications with the economy– “That’s money, the substance that makes the world real. There’s something so corrupt and sexy about it.” He grows from being a fragmentary young boy to a self-assured young man who is confident in his sense of self.

What makes this journey of two flawed individuals so beautiful is the support they give to each other during this search for their independent personhood. Their teenage narcissism of wanting to be so different and being so absolutely conscious of how they don’t fit in, settles into being at ease with this difference and accepting that there will always be more similarities that they’ll have with the world at large rather than differences. Add to this Rooney’s Marxist perspective on class and wealth, and the fresh breath of technology she laces into the work– without it being jarring, rather, being much more natural– you have a well-written piece of fiction. I like to think we are an epistolary generation; our feelings are communicated over text, just like they were generations ago. The only difference is the time frame these words are delivered. This changes the literary territory we are used to; our online personas creep into literature, our humor and our communication. This is what makes the end so special– we have no clue where it will take our beloved characters, just a note of hope.

I would like to say frankly, that this show and book is one that resonated with me on a level I still can’t shake off. Perhaps that is what makes Rooney’s work so special– she is polemic, and manages to capture our societal norms and modern-day culture in her books, mostly set in the quintessential Irish landscape, with a lucidity many lack. Her characters are sharp, witty, flawed humans who allow us a glimpse into ourselves. Why I found this so heart-wrenching was because ever-giving, chockfull of kindness, Marianne answers the door at the start of the narrative. “Marianne answers the door when Connell rings the bell.” And just like that, towards the end their strings of fate tie in with a, “I’ll be here; you know that.” This was noted by many of the readers as being something that left them sobbing, and frankly I understand it. It’s definitely something you can’t put down once you have started it, and one that lives up to its popularity.