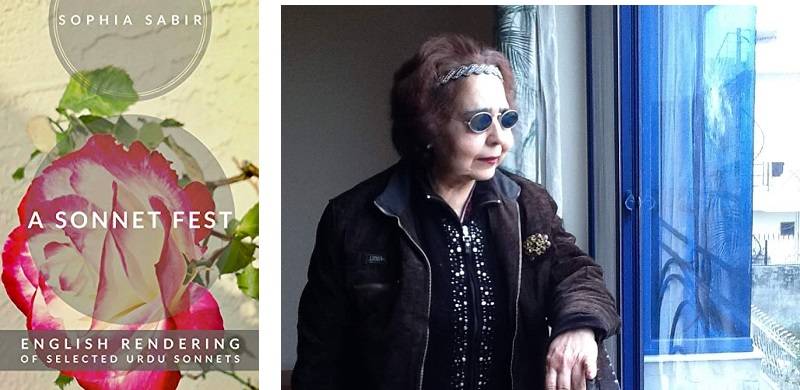

It is rare to come across a writer who is so devoted to the written word that she cares far less to publish and showcase her work than to write more of it and get it right. Sophia Niazeen Sabir, who happens to be my aunt and one of my earliest influences as a literature afficionado, is such a writer. Not only has she been a tireless reader herself, she was the one to cultivate my reading habit and help me develop a lifelong curiosity about language. Having taught Literature for many years in her youth, she has a facility for discussing all genres— from drama, literary travelogue and the novel, to epic, lyric and narrative poetry, to ghazal, ruba’i and even the paheli (rhymed riddle) and the limerick. She has spent decades in the deep study of masterworks— Rumi’s Mathnavi, Sa’adi’s Bustaan, Shakespeare’s Sonnets, works of both poetry and prose in French, Arabic, Urdu and other languages. She has worked painstakingly across literature in different languages and has written translations and commentary on many works. When I received her manuscript A Sonnet Fest, a compilation of Urdu Sonnets translated into English, ready for publication, it was not from the author but from her sister, my mother. It took much convincing for Sophia Niazeen to agree to have the translations published with editorial support from another aunt— Dr. Abida Ripley.

Before reading the manuscript of A Sonnet Fest, I had only read the haiku as a foreign form adapted into Urdu; I had no idea that the Urdu sonnet is not only in existence but it already has a venerable tradition in Urdu literature, starting (likely) from the “Shair e Mashriq” (“Poet of the East”) Muhammad Iqbal himself. As I read the translations and the originals, I was amazed by both the abundance and the variety of Urdu Sonneteers who are well-known, distinctive poets: Akhtar Sheerani, N.M. Rashid, Munir Niazi, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Ibn-e-Insha, to name a few.

The sonnet is originally an Italian poetic form (commonly known as the Petrarchan Sonnet) that entered English centuries ago and has been adapted ever since— the best known adaptation being the “Shakespearean Sonnet.” The sonnet is identified as a 14-line poem written in iambic pentameter with one of the prescribed rhyme schemes and a thematic structure. Being a popular form, its inclusion in Urdu literature seems to have been inevitable.

A Sonnet Fest is a unique contribution to Urdu literature in translation; it is a window into the diverse world of the sonnet itself. The more I grow as a writer the more I treasure a deeply studied translation. Having dabbled in translation myself, I understand just how difficult it is to honor the aesthetic values of two languages at once, to select among semantic and sonic shades in the language one is working with in order to match the effects of the original. Sophia Niazeen’s attempt is immensely laudable as her English translation is not only sensitive to tonal and semantic subtleties of the original but is a rendering in verse.

As with many other translators of Urdu classical poets such as Iqbal, Sophia Niazeen has chosen an elevated register rather than the relaxed contemporary vernacular. Some of my favorite, and in my view the more challenging translations in the book are of Iqbal’s sonnets. Here are a few verses from Mah-e-Nau (“New Moon”) by Iqbal:

Did the sky steal the earring of dusk’s bride?

Is it a raw-silver fish—the Nile’s pride?

Thy caravan moves without a bell;

The human ear perceives not where your foot fell

As Urdu poets adapt Shakespearian or Petrarchan sonnets, they mold and reshape the form in much the same ways as we do when borrowing the ghazal, pantoum or haiku forms for English poetry. They play with structure, meter and syntax, they create something fresh from a time-tested form. Sophia Niazeen discerns these nuances and helps the reader of Urdu poetry by categorising the poems as “Nazm Sonnet,” “Ghazal Sonnet,” so on, depending on the poet’s choices in end rhymes and lineation. I consider this a very useful book for scholars who are attempting to study the mechanics of formal poetry through the filters of English and Urdu. An example is this the 14-line “ghazal” sonnet structured in couplets; here are lines from Iqbal’s sonnet “Irtiqa” (Evolution):

Strife of seasons— the feverish chiseling,

To Aleppo’s fine crystal, from dark clay nought!

Binding, breaking, spreading, firing and brewing,

Pearl-making drop to the fire of the grape—taught

Wine-makers, with a bunch of grapes, have once done,

And may still— crush up the stars— create a Sun

A Sonnet Fest offers a treasure in its compilation and English verse rendering and I am very grateful that a book such as this exists as a resource for further study. Here are the comments I happily wrote when the author agreed to have the book published:

A poetic form is a language unto itself; it may originate in one culture but its journey is often mapped across varied, and even seemingly divergent cultures where it finds nuance and freshness. Forms such as the Pantoum originated in Malay and entered English Literature via French, the Ghazal, originally an Arabic form, was transferred to English through the currents of Persian and Urdu literature, the Haiku, similarly, is originally Japanese but its formal structure is ardently followed in multiple languages. The tradition of the Sonnet, too, goes back centuries, and as a popular form which found appeal in many cultures including the English, it has had many transmutations across literatures and literary periods. A Sonnet Fest shows us that this classic Italian form has inspired Urdu poets of many generations who have penned variations of the sonnet.

Poetry in translation is at once an interpretive and a creative offering, one that is vital to the larger appreciation and further enrichment of world literature. A Sonnet Fest is a unique book of sonnets composed by some of the best-known Urdu poets and rendered into English by Sophia Niazeen Sabir. Behind this book are years and years of study by the translator, not only of the literary traditions of the East and West but also of history and culture. Niazeen Sabir has carefully selected Urdu sonnets that represent a wide range of styles and themes, showcasing the different ways the sonnet form has been adapted into Urdu. Her translations aim to preserve the rhyme-scheme of the original which is quite a feat across two literary traditions of different aesthetic sensibilities. This book is a remarkable gift that enlarges and enhances the conversation of craft and culture.

Before reading the manuscript of A Sonnet Fest, I had only read the haiku as a foreign form adapted into Urdu; I had no idea that the Urdu sonnet is not only in existence but it already has a venerable tradition in Urdu literature, starting (likely) from the “Shair e Mashriq” (“Poet of the East”) Muhammad Iqbal himself. As I read the translations and the originals, I was amazed by both the abundance and the variety of Urdu Sonneteers who are well-known, distinctive poets: Akhtar Sheerani, N.M. Rashid, Munir Niazi, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Ibn-e-Insha, to name a few.

The sonnet is originally an Italian poetic form (commonly known as the Petrarchan Sonnet) that entered English centuries ago and has been adapted ever since— the best known adaptation being the “Shakespearean Sonnet.” The sonnet is identified as a 14-line poem written in iambic pentameter with one of the prescribed rhyme schemes and a thematic structure. Being a popular form, its inclusion in Urdu literature seems to have been inevitable.

A Sonnet Fest is a unique contribution to Urdu literature in translation; it is a window into the diverse world of the sonnet itself. The more I grow as a writer the more I treasure a deeply studied translation. Having dabbled in translation myself, I understand just how difficult it is to honor the aesthetic values of two languages at once, to select among semantic and sonic shades in the language one is working with in order to match the effects of the original. Sophia Niazeen’s attempt is immensely laudable as her English translation is not only sensitive to tonal and semantic subtleties of the original but is a rendering in verse.

Poetry in translation is at once an interpretive and a creative offering, one that is vital to the larger appreciation and further enrichment of world literature

As with many other translators of Urdu classical poets such as Iqbal, Sophia Niazeen has chosen an elevated register rather than the relaxed contemporary vernacular. Some of my favorite, and in my view the more challenging translations in the book are of Iqbal’s sonnets. Here are a few verses from Mah-e-Nau (“New Moon”) by Iqbal:

Did the sky steal the earring of dusk’s bride?

Is it a raw-silver fish—the Nile’s pride?

Thy caravan moves without a bell;

The human ear perceives not where your foot fell

As Urdu poets adapt Shakespearian or Petrarchan sonnets, they mold and reshape the form in much the same ways as we do when borrowing the ghazal, pantoum or haiku forms for English poetry. They play with structure, meter and syntax, they create something fresh from a time-tested form. Sophia Niazeen discerns these nuances and helps the reader of Urdu poetry by categorising the poems as “Nazm Sonnet,” “Ghazal Sonnet,” so on, depending on the poet’s choices in end rhymes and lineation. I consider this a very useful book for scholars who are attempting to study the mechanics of formal poetry through the filters of English and Urdu. An example is this the 14-line “ghazal” sonnet structured in couplets; here are lines from Iqbal’s sonnet “Irtiqa” (Evolution):

Strife of seasons— the feverish chiseling,

To Aleppo’s fine crystal, from dark clay nought!

Binding, breaking, spreading, firing and brewing,

Pearl-making drop to the fire of the grape—taught

Wine-makers, with a bunch of grapes, have once done,

And may still— crush up the stars— create a Sun

A Sonnet Fest offers a treasure in its compilation and English verse rendering and I am very grateful that a book such as this exists as a resource for further study. Here are the comments I happily wrote when the author agreed to have the book published:

A poetic form is a language unto itself; it may originate in one culture but its journey is often mapped across varied, and even seemingly divergent cultures where it finds nuance and freshness. Forms such as the Pantoum originated in Malay and entered English Literature via French, the Ghazal, originally an Arabic form, was transferred to English through the currents of Persian and Urdu literature, the Haiku, similarly, is originally Japanese but its formal structure is ardently followed in multiple languages. The tradition of the Sonnet, too, goes back centuries, and as a popular form which found appeal in many cultures including the English, it has had many transmutations across literatures and literary periods. A Sonnet Fest shows us that this classic Italian form has inspired Urdu poets of many generations who have penned variations of the sonnet.

Poetry in translation is at once an interpretive and a creative offering, one that is vital to the larger appreciation and further enrichment of world literature. A Sonnet Fest is a unique book of sonnets composed by some of the best-known Urdu poets and rendered into English by Sophia Niazeen Sabir. Behind this book are years and years of study by the translator, not only of the literary traditions of the East and West but also of history and culture. Niazeen Sabir has carefully selected Urdu sonnets that represent a wide range of styles and themes, showcasing the different ways the sonnet form has been adapted into Urdu. Her translations aim to preserve the rhyme-scheme of the original which is quite a feat across two literary traditions of different aesthetic sensibilities. This book is a remarkable gift that enlarges and enhances the conversation of craft and culture.