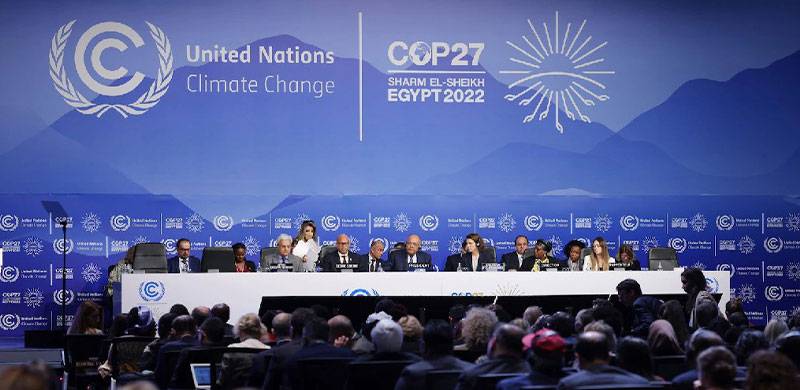

The Conference of Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention took place for the 27th time in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt earlier this month. The outcome was no different than the 26 previous occasions in that the global community agreed to come back in the ensuing year to repeat the exercise.

But such is the idiosyncratic nature of climate negotiations.

The COPs under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) were conceived with one primary goal -- to stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system.”

Yet, since the global community ratified the Framework Convention, the emission levels have continued to grow. Consider the fact that over half the greenhouse emissions globally have come over the last 30 years.

In May 1992 when the UNFCCC was ratified during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere were calculated to be 359.99 parts per million (ppm), above the 350 ppm that scientists agree to be the safe upper limit of CO2 concentrations. The United States NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory measured CO2 concentration at 421 parts per million in May, earlier this year. Such high concentration levels have not been witnessed on this planet for millions of years.

The consequences, as we saw in Pakistan this year, are quite severe for the most vulnerable communities.

It is in this context that the world leaders gathered in Sharm El Sheikh. The Conference of Parties was labelled the ‘COP of implementation’, which makes one wonder about the raison d'être of the 26 previous ones.

Pakistan Federal Minister for Climate Change, Sherry Rehman, was vociferous in speaking on behalf of vulnerable communities across the global south. Her refrain -- what goes on in Pakistan (vis-à-vis climate change) will not stay within Pakistan -- found resonance among not only climate vulnerable countries but also amongst climate activists. Pakistan, as Chair of the G77 plus China, played an instrumental role in keeping a united front even as countries in the global north tried to induce fissures within the coalition. Not only was Loss and Damage finally given a place on the COP agenda, the conference concluded with a decision to develop a Loss and Damage Finance Facility, a long-standing demand of the developing countries.

A boisterous civil society movement that has been calling for climate justice without fail over the past 30 years further strengthened Pakistan’s stance.

Yet, a Loss and Damage Facility is a battle front victory in a losing war effort. It is an acknowledgment that we have failed to address the cause of the climate crisis. It is also an acknowledgment that we may continue to ignore it.

Moreover, there is no guarantee that a Loss and Damage Facility will be the purveyor of funding necessary to address the very real losses and damages that communities suffer as a result of the climate crisis. Consider the fact that the commitment to make available funding for mitigation and adaptation to the tune of USD100 billion on annual basis by 2020 (at COP15 in Copenhagen) is yet to be fulfilled. Of whatever little funding is available, most goes towards mitigation and not adaptation, the primary need of low emission countries such as Pakistan. Also, the climate financing is for the most part made up of concessional or non-concessional loans instead of grants.

COP27 saw the development of a Global Shield financing facility to address loss and damage in vulnerable countries. The first recipients are expected to include Pakistan, Ghana and Bangladesh. However, the funds allocated, thus far, as part of this are only around 200 million euros. No points for guessing whether these funds are substantial enough to deal with very real losses and damages happening in vulnerable communities in the global south.

Further, this initiative has come under scrutiny for potentially undercutting the funding that may eventually be made available under the Loss and Damage Facility.

According to the Pakistan Disaster Needs Assessment, conducted in the aftermath of this year’s floods, the losses and damages amount to USD30 billion with an additional USD15 billion required to build back resiliently. It will be a fool’s errand to think that somehow the global north will contribute even a 10th of the funds required to address such needs, not only in Pakistan but across other climate vulnerable countries.

The COP of Implementation turned out to be anything but. The demands for the COP cover decision to include fossil fuel phase out fizzled even as ‘low emission energy,’ a reference to natural gas, was added in its stead. Until now coal has been the focus of mitigation initiatives yet we know that oil and gas also contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. The lobbying efforts of the oil and gas producing countries, and penchant of the developed world, and more recently India and China to use coal to meet their growing energy needs has severely hampered efforts to limit atmospheric pollution. Indeed, we are expected to exceed the 1.5 centigrade temperature rise since the industrial age in about a decade. This is a dangerous omen for vulnerable communities in Pakistan.

The heatwave and floods of 2022 may not yet be a distant memory before we are faced with another episode of climate induced extreme weather event and ensuing catastrophe. This necessitates putting our own house in order, and addressing the plethora of governance issues that exacerbated the impact of recent floods, for example. These are the low hanging fruits that if utilized properly can help us respond to the climate crisis in a holistic and meaningful manner.

The essence of such an approach is to put communities at the center of our decision-making. It necessitates the development of a functional local government system, improved coordination between ministries and line departments at the federal and provincial levels, formation of an effective and people-centered early warning system, ensuring that land use plans are developed and implemented, conducting detailed local level risk and hazard assessments, and using nature-based solutions to address those hazards.

At the same time, we should continue to call on the developed world to eliminate greenhouse gas pollution and take steps to address the climate financing needs of the developing countries, be they in terms of mitigation, adaptation or loss and damage, for what goes on in Pakistan truly won’t stay in Pakistan!

But such is the idiosyncratic nature of climate negotiations.

The COPs under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) were conceived with one primary goal -- to stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system.”

Yet, since the global community ratified the Framework Convention, the emission levels have continued to grow. Consider the fact that over half the greenhouse emissions globally have come over the last 30 years.

In May 1992 when the UNFCCC was ratified during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere were calculated to be 359.99 parts per million (ppm), above the 350 ppm that scientists agree to be the safe upper limit of CO2 concentrations. The United States NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory measured CO2 concentration at 421 parts per million in May, earlier this year. Such high concentration levels have not been witnessed on this planet for millions of years.

The consequences, as we saw in Pakistan this year, are quite severe for the most vulnerable communities.

It is in this context that the world leaders gathered in Sharm El Sheikh. The Conference of Parties was labelled the ‘COP of implementation’, which makes one wonder about the raison d'être of the 26 previous ones.

Pakistan Federal Minister for Climate Change, Sherry Rehman, was vociferous in speaking on behalf of vulnerable communities across the global south. Her refrain -- what goes on in Pakistan (vis-à-vis climate change) will not stay within Pakistan -- found resonance among not only climate vulnerable countries but also amongst climate activists. Pakistan, as Chair of the G77 plus China, played an instrumental role in keeping a united front even as countries in the global north tried to induce fissures within the coalition. Not only was Loss and Damage finally given a place on the COP agenda, the conference concluded with a decision to develop a Loss and Damage Finance Facility, a long-standing demand of the developing countries.

A boisterous civil society movement that has been calling for climate justice without fail over the past 30 years further strengthened Pakistan’s stance.

A Loss and Damage Facility is a battle front victory in a losing war effort. It is an acknowledgment that we have failed to address the cause of the climate crisis. It is also an acknowledgment that we may continue to ignore it.

Yet, a Loss and Damage Facility is a battle front victory in a losing war effort. It is an acknowledgment that we have failed to address the cause of the climate crisis. It is also an acknowledgment that we may continue to ignore it.

Moreover, there is no guarantee that a Loss and Damage Facility will be the purveyor of funding necessary to address the very real losses and damages that communities suffer as a result of the climate crisis. Consider the fact that the commitment to make available funding for mitigation and adaptation to the tune of USD100 billion on annual basis by 2020 (at COP15 in Copenhagen) is yet to be fulfilled. Of whatever little funding is available, most goes towards mitigation and not adaptation, the primary need of low emission countries such as Pakistan. Also, the climate financing is for the most part made up of concessional or non-concessional loans instead of grants.

COP27 saw the development of a Global Shield financing facility to address loss and damage in vulnerable countries. The first recipients are expected to include Pakistan, Ghana and Bangladesh. However, the funds allocated, thus far, as part of this are only around 200 million euros. No points for guessing whether these funds are substantial enough to deal with very real losses and damages happening in vulnerable communities in the global south.

Further, this initiative has come under scrutiny for potentially undercutting the funding that may eventually be made available under the Loss and Damage Facility.

According to the Pakistan Disaster Needs Assessment, conducted in the aftermath of this year’s floods, the losses and damages amount to USD30 billion with an additional USD15 billion required to build back resiliently. It will be a fool’s errand to think that somehow the global north will contribute even a 10th of the funds required to address such needs, not only in Pakistan but across other climate vulnerable countries.

The COP of Implementation turned out to be anything but. The demands for the COP cover decision to include fossil fuel phase out fizzled even as ‘low emission energy,’ a reference to natural gas, was added in its stead. Until now coal has been the focus of mitigation initiatives yet we know that oil and gas also contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. The lobbying efforts of the oil and gas producing countries, and penchant of the developed world, and more recently India and China to use coal to meet their growing energy needs has severely hampered efforts to limit atmospheric pollution. Indeed, we are expected to exceed the 1.5 centigrade temperature rise since the industrial age in about a decade. This is a dangerous omen for vulnerable communities in Pakistan.

The heatwave and floods of 2022 may not yet be a distant memory before we are faced with another episode of climate induced extreme weather event and ensuing catastrophe. This necessitates putting our own house in order, and addressing the plethora of governance issues that exacerbated the impact of recent floods, for example. These are the low hanging fruits that if utilized properly can help us respond to the climate crisis in a holistic and meaningful manner.

The essence of such an approach is to put communities at the center of our decision-making. It necessitates the development of a functional local government system, improved coordination between ministries and line departments at the federal and provincial levels, formation of an effective and people-centered early warning system, ensuring that land use plans are developed and implemented, conducting detailed local level risk and hazard assessments, and using nature-based solutions to address those hazards.

At the same time, we should continue to call on the developed world to eliminate greenhouse gas pollution and take steps to address the climate financing needs of the developing countries, be they in terms of mitigation, adaptation or loss and damage, for what goes on in Pakistan truly won’t stay in Pakistan!