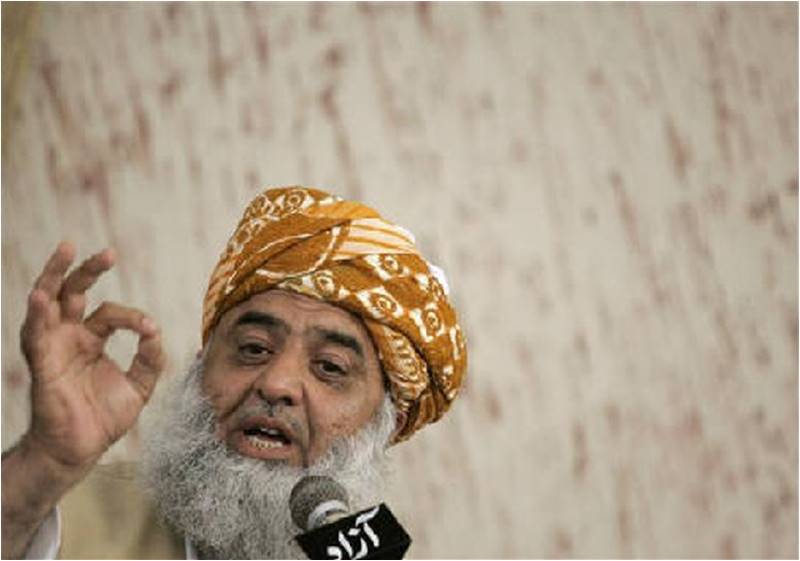

Let me first list what this article is not about. It’s not about the tactics of Fazlur Rehman’s Azadi March by which I mean the various ambiguities that seem to inform that decision and the statements that reflect those ambiguities. It’s not about whether the Pakistan Peoples Party will go along or not; whether PMLN, which is more likely to add some weight to Rehman’s effort, will see Shahbaz Sharif’s presence; whether Bilal Bhutto Zardari will be there; how the marchers will get to Islamabad or whether the government will allow them to get there; whether, if they do get there, they will stay there or leave after a show of strength; whether it’s a good idea for the government to dig up roads that connect Islamabad to its surroundings and the rest of the country.

All of that is tactical and while each statement or action provides material to a plethora of talkshows, it misses the big picture.

And what’s that?

Before answering that question, let’s go back to Mao Zedong’s August 1937 essay, On Contradiction. Mao wrote it to correct what he considered the serious error of dogmatist thinking in the Party at the time. While speaking of the “law of contradiction in things, that is, the law of the unity of opposites,” he attempted to deal with “the universality of contradiction, the particularity of contradiction, the principal contradiction and the principal aspect of a contradiction, the identity and struggle of the aspects of a contradiction, and the place of antagonism in contradiction.”

For our purpose here, we shall focus on the principal contradiction.

While Mao gives multiple examples of universal contradiction in various fields of science and of human activity, he stresses that each situation also contains in it the particularity of contradiction. In other words, the law of contradiction is not immutable but dynamic and particular situations (or conflicts) would necessitate understanding and situating the principal contradiction correctly.

“[The] situation is not static; the principal and the non-principal aspects of a contradiction transform themselves into each other and the nature of the thing changes accordingly. In a given process or at a given stage in the development of a contradiction, A is the principal aspect and B is the non-principal aspect; at another stage or in another process the roles are reversed — a change determined by the extent of the increase or decrease in the force of each aspect in its struggle against the other in the course of the development of a thing.”

Put another way, while there may be many secondary contradictions in play, there will always be one principal contradiction in a situation and grasping that is important both for analysing the situation and its dynamics and taking action. If China is facing an imperial power which has turned it into a semi-colony, the principal contradiction will be between the peoples and the imperial power. That will translate into a struggle of the peoples against that imperialism. But once the peoples win that war, the principal contradiction will shift to other contradictions, one of which, at that stage, would play the part of the principal contradiction.

The dogmatists, according to Mao, are wrong in insisting that every situation must be dealt with according to some unchanging conceptual or actionable framework.

At this point let’s go back to the bigger picture here and open up that discussion with what is being said about the ‘liberals’ in the current political situation. I put the term liberal in inverted commas to denote the particular reference, often pejorative, in Pakistan’s context, as opposed to its philosophical one.

Why are the liberals supporting Fazlur Rehman, decidedly a regressive cleric, heading an equally regressive religion-political party? Isn’t that a contradiction? Why is the PMLN, a centrist, centre-right party aligned with Rehman? Worse, why is the PPP, that calls itself a liberal party, going along with Rehman? How come the late Asma Jehangir is being celebrated by elements that were opposed to her liberal ideas?

All these and many other questions are raised by partisans, depending on where they stand and who they support. They select their own facts. For instance, the PTI leaders and the party’s social media cadres appear to be deeply concerned about the writ of the state and the sensitive situation the country is passing through and somehow cannot figure out why Rehman and the rest of the opposition are bent upon rocking the boat.

It’s quite another thing that only a year-and-half ago they were quite happy to challenge the writ of the state and not just rock the boat but sink it.

These views are of course not analysis. Analysis requires studying the situation and finding the principal contradiction. Since India’s August 5 action and subsequent threats of aggression, is the principal contradiction between Pakistan and that country? In the event that India begins an armed conflict with Pakistan, sure. The issue then would be the survival of this country, not the multiple contradictions that inform its existence internally. All Pakistanis will then face the Indian threat and neutralise it.

But that, in and of itself, will not take care of other contradictions. Once that threat is neutralised, we will have to face the other contradictions. One contradiction that continues to run through this country is between a civilian, democratic system and a military with praetorian tendencies. Where do we place it at this moment?

There were other contradictions: for instance, during his second tenure, Mian Nawaz Sharif and his PMLN showed both dictatorial and regressive signs. In that situation, the liberals stood with the PPP. Both the PPP and the PMLN played a zero-sum game with the military in the role of the arbiter. Where did the principal contradiction lie then?

The PTI partisan would turn around and say that there is a civilian government in place today and, therefore, one cannot, should not, invoke the principal contradiction between the civilians and the military. [NB: I shan’t even get into the usual mantra of ‘Oh, the PPP and the PMLN were robbers and looted this country.’ That argument has become stale even for the more discerning PTI supporter. As for the process of accountability, the less said the better.]

The fact is that PTI is where it is because of an ‘experiment’. An experiment that is not just failing but has failed. The dispensation was put together by getting the detritus from other parties, the same parties that the PTI wouldn’t tire of castigating.

The prime minister says he doesn’t have a team. About that he is right. But that also calls for some reflection. As the leader, was it not his duty, and, in equal measure, is that not his failure, to put together a team that could deliver? On the other hand, one plays with what one has got, not what one desires.

So, the argument that this dispensation is a civilian one, or is empowered, is flawed. It’s not about the facade, much less about the charade. It’s about facts. And the fact is that this government is sustaining because of the very force that cobbled it.

If you find the liberal standing with Rehman, don’t call it the liberal’s contradiction. He is responding to the principal contradiction. Once the principal contradiction gets resolved, the situation will demand a shift to the contradiction between regressive Rehman and those espousing liberal-secularism.

Meanwhile, if tomorrow Rehman were to step back from what he has promised to do, who do you think would have prevailed upon him to do so? The government? Nope!

Well, in that case you do know where the principal contradiction is.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He finds the principal contradiction too hot to handle! He tweets @ejazhaider

All of that is tactical and while each statement or action provides material to a plethora of talkshows, it misses the big picture.

And what’s that?

Before answering that question, let’s go back to Mao Zedong’s August 1937 essay, On Contradiction. Mao wrote it to correct what he considered the serious error of dogmatist thinking in the Party at the time. While speaking of the “law of contradiction in things, that is, the law of the unity of opposites,” he attempted to deal with “the universality of contradiction, the particularity of contradiction, the principal contradiction and the principal aspect of a contradiction, the identity and struggle of the aspects of a contradiction, and the place of antagonism in contradiction.”

For our purpose here, we shall focus on the principal contradiction.

While Mao gives multiple examples of universal contradiction in various fields of science and of human activity, he stresses that each situation also contains in it the particularity of contradiction. In other words, the law of contradiction is not immutable but dynamic and particular situations (or conflicts) would necessitate understanding and situating the principal contradiction correctly.

“[The] situation is not static; the principal and the non-principal aspects of a contradiction transform themselves into each other and the nature of the thing changes accordingly. In a given process or at a given stage in the development of a contradiction, A is the principal aspect and B is the non-principal aspect; at another stage or in another process the roles are reversed — a change determined by the extent of the increase or decrease in the force of each aspect in its struggle against the other in the course of the development of a thing.”

Put another way, while there may be many secondary contradictions in play, there will always be one principal contradiction in a situation and grasping that is important both for analysing the situation and its dynamics and taking action. If China is facing an imperial power which has turned it into a semi-colony, the principal contradiction will be between the peoples and the imperial power. That will translate into a struggle of the peoples against that imperialism. But once the peoples win that war, the principal contradiction will shift to other contradictions, one of which, at that stage, would play the part of the principal contradiction.

The dogmatists, according to Mao, are wrong in insisting that every situation must be dealt with according to some unchanging conceptual or actionable framework.

At this point let’s go back to the bigger picture here and open up that discussion with what is being said about the ‘liberals’ in the current political situation. I put the term liberal in inverted commas to denote the particular reference, often pejorative, in Pakistan’s context, as opposed to its philosophical one.

Why are the liberals supporting Fazlur Rehman, decidedly a regressive cleric, heading an equally regressive religion-political party? Isn’t that a contradiction? Why is the PMLN, a centrist, centre-right party aligned with Rehman? Worse, why is the PPP, that calls itself a liberal party, going along with Rehman? How come the late Asma Jehangir is being celebrated by elements that were opposed to her liberal ideas?

All these and many other questions are raised by partisans, depending on where they stand and who they support. They select their own facts. For instance, the PTI leaders and the party’s social media cadres appear to be deeply concerned about the writ of the state and the sensitive situation the country is passing through and somehow cannot figure out why Rehman and the rest of the opposition are bent upon rocking the boat.

It’s quite another thing that only a year-and-half ago they were quite happy to challenge the writ of the state and not just rock the boat but sink it.

These views are of course not analysis. Analysis requires studying the situation and finding the principal contradiction. Since India’s August 5 action and subsequent threats of aggression, is the principal contradiction between Pakistan and that country? In the event that India begins an armed conflict with Pakistan, sure. The issue then would be the survival of this country, not the multiple contradictions that inform its existence internally. All Pakistanis will then face the Indian threat and neutralise it.

But that, in and of itself, will not take care of other contradictions. Once that threat is neutralised, we will have to face the other contradictions. One contradiction that continues to run through this country is between a civilian, democratic system and a military with praetorian tendencies. Where do we place it at this moment?

There were other contradictions: for instance, during his second tenure, Mian Nawaz Sharif and his PMLN showed both dictatorial and regressive signs. In that situation, the liberals stood with the PPP. Both the PPP and the PMLN played a zero-sum game with the military in the role of the arbiter. Where did the principal contradiction lie then?

The PTI partisan would turn around and say that there is a civilian government in place today and, therefore, one cannot, should not, invoke the principal contradiction between the civilians and the military. [NB: I shan’t even get into the usual mantra of ‘Oh, the PPP and the PMLN were robbers and looted this country.’ That argument has become stale even for the more discerning PTI supporter. As for the process of accountability, the less said the better.]

The fact is that PTI is where it is because of an ‘experiment’. An experiment that is not just failing but has failed. The dispensation was put together by getting the detritus from other parties, the same parties that the PTI wouldn’t tire of castigating.

The prime minister says he doesn’t have a team. About that he is right. But that also calls for some reflection. As the leader, was it not his duty, and, in equal measure, is that not his failure, to put together a team that could deliver? On the other hand, one plays with what one has got, not what one desires.

So, the argument that this dispensation is a civilian one, or is empowered, is flawed. It’s not about the facade, much less about the charade. It’s about facts. And the fact is that this government is sustaining because of the very force that cobbled it.

If you find the liberal standing with Rehman, don’t call it the liberal’s contradiction. He is responding to the principal contradiction. Once the principal contradiction gets resolved, the situation will demand a shift to the contradiction between regressive Rehman and those espousing liberal-secularism.

Meanwhile, if tomorrow Rehman were to step back from what he has promised to do, who do you think would have prevailed upon him to do so? The government? Nope!

Well, in that case you do know where the principal contradiction is.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He finds the principal contradiction too hot to handle! He tweets @ejazhaider