Sara Danial: You see cricket as a collective cultural expression of society – that the sport entails political discourse, social order, culture, class dynamics, religion, etc. It channels the conflicts rooted in our nation. Could you elaborate on it?

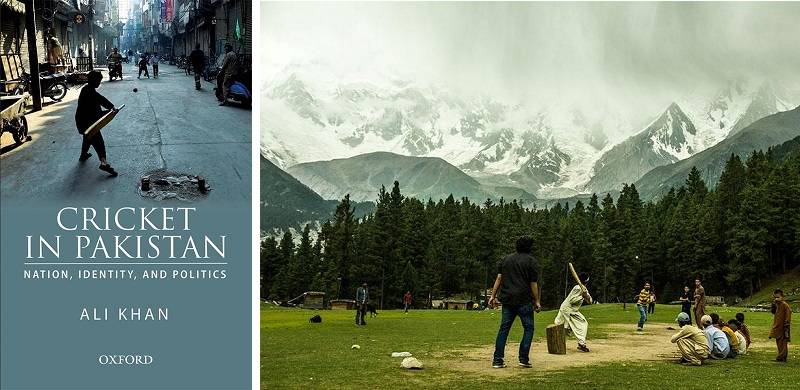

Ali Khan: Yes, I think this is the basic premise of the book – that cricket has come to act as a microcosm or reflection of society—its politics, history, culture, and aspirations. In Pakistan, cricket is a metaphor for modern life—from the youthful exuberance, energy, and innovation of a young nation, to increasing religiosity, aspects of corruption, and global relations. Pakistan was energetic, unfettered, and dazzling. But it was also corrupt, undisciplined, disorderly, and chaotic. No other sphere of life articulates Pakistan’s history, culture, society, and economy more precisely than the cultural practice of cricket. But, cricket, like other sports, is also a multi-billion-dollar industry with far-reaching social and economic consequences. It is thereby able to create and communicate meaning, giving it the ability to affect the culture of the society in which it is embedded. Sport defines cultures, drives economies, and shapes politics.

SD: The corporates have millions riding on the games. To increase their marketability, they hire sports stars to be the brand ambassadors of their products, investing in the saleability of the game and its icon. Distinct social meanings can be constructed and deconstructed through this sport and their interplay with society. Do you think it is a necessary evil that comes along with the passion for the game?

AK: I think commercialisation came to cricket quite late starting with World Series Cricket in the late 1970s and building from that. Every sport needs finances to sustain and grow so, in that sense, commercialization is a necessary evil but it can be channeled very productively to strengthen the sport itself. There are, of course, dangers that lurk with rapid commercialisation and we have seen that with the match-fixing scandals that have hit all countries. We also see it increasingly with the pull of lucrative T20 leagues clashing with national duties. This is all made more acute in cricket because the game comes infused with a very specific moralistic ideology that contradicts the reality of its political economy in the age of late capitalism. Commercialization is definitely changing cricket’s old ethos, replacing it with a new set of values, what the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls the ‘transcendence of traditional cricketing norms and values’ where making money features more prominently than the ‘spirit of the game’ or its nationalist concerns. Globalization is stripping the nationalist identity of players away, making them hostage to market processes. This is captured most starkly in the Twenty20 practice of auctions, where players are sold to the highest bidder. Lists are then published with sold players and the price they obtained and those unwanted ones who remain unsold.

SD: Do you believe in “hegemonic sports culture” in which only a few sports become a part of the popular culture? Does watching, following, worrying, debating, living, and speaking a sport rather than merely playing it, make it popular, or has it evolved as an inherent social milieu and the life of the people of Pakistan after the British Raj?

AK: Sport is part of popular culture and imagination. It is not confined to those who simply play it. Cricket has captured Pakistan’s national imagination since the country’s birth. It had already laid down strong roots prior to Partition as well. It’s no wonder that Ashis Nandy referred to it as an Indian game accidentally discovered by the British. But the very popularity of the game in the subcontinent has stymied the growth of other sports which we should have supported more. We had a very proud history in hockey and squash for example and a lack of attention to these sports is a disservice to those who brought such laurels to Pakistan within these sports. Pakistan’s sports require much more support beyond cricket despite cricket’s immense popularity.

SD: Your book discusses the unfortunate incident in which the Sri Lankan team was attacked that cornered Pakistan in the cricketing circuit. Have we, in any way, risen above and beyond? Will we ever transcend that black spot to change the narrative tied to Pakistan’s security concerns?

AK: We have made significant progress in rising from the ashes of that terrible time. It was so poignant that the first team to return to Pakistan for a test match tour was Sri Lanka in 2019. And the return of cricket has been the efforts of many different institutions over an extended period of time. Support has been provided by the Pakistan Cricket Board, different governments, the army which was responsible for security and, of course, the fans that have shown that Pakistan is a welcoming and cricket-mad nation. But the situation remains sensitive. Overcoming narratives and stereotypes requires building counter-narratives. And, again, cricket is embedded in the wider social, economic and political milieu. If, as a country, we are able to bring about stability and security to the nation, then cricket thrives. If not, it remains precarious.

SD: Games against India are not just a sport. It is a rivalry, between leaders, nations, people, and so much more. It creates an aura in itself with everyone glued to the game. What are the chances of bringing back this level of excitement and entertainment to the nation?

AK: It’s one of the most compelling of all sporting rivalries and the unfortunate political situation between the two countries has deprived cricket fans on both sides of the border, and across the world, of this unique encounter. Not playing on the sporting field and the political ill will on both sides also begin to change the mindset of people on both sides towards viewing each other not as archrivals but as enemies. That mindset will always hold the South Asian region back from progress and fulfilling the enormous potential of the area, and that is a tragedy. We have had long breaks in bilateral cricketing relations in the past – the current one is one of the longest – but we have bounced back and reignited this relationship. I hope both India and Pakistan can begin to take steps towards a gradual reset of relations so that both countries benefit mutually. Maybe the winners of the PSL and IPL tournaments could play initially. Small steps and a commitment to peace, prosperity and our unique historical and cricketing bond.

Ali Khan: Yes, I think this is the basic premise of the book – that cricket has come to act as a microcosm or reflection of society—its politics, history, culture, and aspirations. In Pakistan, cricket is a metaphor for modern life—from the youthful exuberance, energy, and innovation of a young nation, to increasing religiosity, aspects of corruption, and global relations. Pakistan was energetic, unfettered, and dazzling. But it was also corrupt, undisciplined, disorderly, and chaotic. No other sphere of life articulates Pakistan’s history, culture, society, and economy more precisely than the cultural practice of cricket. But, cricket, like other sports, is also a multi-billion-dollar industry with far-reaching social and economic consequences. It is thereby able to create and communicate meaning, giving it the ability to affect the culture of the society in which it is embedded. Sport defines cultures, drives economies, and shapes politics.

"Cricket has captured Pakistan’s national imagination since the country’s birth. It had already laid down strong roots prior to partition as well. It’s no wonder that Ashis Nandy referred to it as an Indian game accidentally discovered by the British"

SD: The corporates have millions riding on the games. To increase their marketability, they hire sports stars to be the brand ambassadors of their products, investing in the saleability of the game and its icon. Distinct social meanings can be constructed and deconstructed through this sport and their interplay with society. Do you think it is a necessary evil that comes along with the passion for the game?

AK: I think commercialisation came to cricket quite late starting with World Series Cricket in the late 1970s and building from that. Every sport needs finances to sustain and grow so, in that sense, commercialization is a necessary evil but it can be channeled very productively to strengthen the sport itself. There are, of course, dangers that lurk with rapid commercialisation and we have seen that with the match-fixing scandals that have hit all countries. We also see it increasingly with the pull of lucrative T20 leagues clashing with national duties. This is all made more acute in cricket because the game comes infused with a very specific moralistic ideology that contradicts the reality of its political economy in the age of late capitalism. Commercialization is definitely changing cricket’s old ethos, replacing it with a new set of values, what the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls the ‘transcendence of traditional cricketing norms and values’ where making money features more prominently than the ‘spirit of the game’ or its nationalist concerns. Globalization is stripping the nationalist identity of players away, making them hostage to market processes. This is captured most starkly in the Twenty20 practice of auctions, where players are sold to the highest bidder. Lists are then published with sold players and the price they obtained and those unwanted ones who remain unsold.

SD: Do you believe in “hegemonic sports culture” in which only a few sports become a part of the popular culture? Does watching, following, worrying, debating, living, and speaking a sport rather than merely playing it, make it popular, or has it evolved as an inherent social milieu and the life of the people of Pakistan after the British Raj?

AK: Sport is part of popular culture and imagination. It is not confined to those who simply play it. Cricket has captured Pakistan’s national imagination since the country’s birth. It had already laid down strong roots prior to Partition as well. It’s no wonder that Ashis Nandy referred to it as an Indian game accidentally discovered by the British. But the very popularity of the game in the subcontinent has stymied the growth of other sports which we should have supported more. We had a very proud history in hockey and squash for example and a lack of attention to these sports is a disservice to those who brought such laurels to Pakistan within these sports. Pakistan’s sports require much more support beyond cricket despite cricket’s immense popularity.

SD: Your book discusses the unfortunate incident in which the Sri Lankan team was attacked that cornered Pakistan in the cricketing circuit. Have we, in any way, risen above and beyond? Will we ever transcend that black spot to change the narrative tied to Pakistan’s security concerns?

AK: We have made significant progress in rising from the ashes of that terrible time. It was so poignant that the first team to return to Pakistan for a test match tour was Sri Lanka in 2019. And the return of cricket has been the efforts of many different institutions over an extended period of time. Support has been provided by the Pakistan Cricket Board, different governments, the army which was responsible for security and, of course, the fans that have shown that Pakistan is a welcoming and cricket-mad nation. But the situation remains sensitive. Overcoming narratives and stereotypes requires building counter-narratives. And, again, cricket is embedded in the wider social, economic and political milieu. If, as a country, we are able to bring about stability and security to the nation, then cricket thrives. If not, it remains precarious.

SD: Games against India are not just a sport. It is a rivalry, between leaders, nations, people, and so much more. It creates an aura in itself with everyone glued to the game. What are the chances of bringing back this level of excitement and entertainment to the nation?

AK: It’s one of the most compelling of all sporting rivalries and the unfortunate political situation between the two countries has deprived cricket fans on both sides of the border, and across the world, of this unique encounter. Not playing on the sporting field and the political ill will on both sides also begin to change the mindset of people on both sides towards viewing each other not as archrivals but as enemies. That mindset will always hold the South Asian region back from progress and fulfilling the enormous potential of the area, and that is a tragedy. We have had long breaks in bilateral cricketing relations in the past – the current one is one of the longest – but we have bounced back and reignited this relationship. I hope both India and Pakistan can begin to take steps towards a gradual reset of relations so that both countries benefit mutually. Maybe the winners of the PSL and IPL tournaments could play initially. Small steps and a commitment to peace, prosperity and our unique historical and cricketing bond.