In October 1958, Ayub Khan became Pakistan’s first military dictator and promptly banned student politics and unions. In 1962, the student movement in Pakistan, like its counterparts in India and around the world, split into pro-Beijing and pro-Moscow factions tussling for power, which benefitted a new entrant to student politics, the Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (IJT), the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami. Socially too, many college students like the eponymous hero of the novel had begun arriving from the rural and conservative countryside to cities like Karachi, where they were indoctrinated by the likes of NSF or IJT. It is impossible to understand the novel’s subsequent story without these political and social developments in the Pakistan of the 1950s and ‘60s.

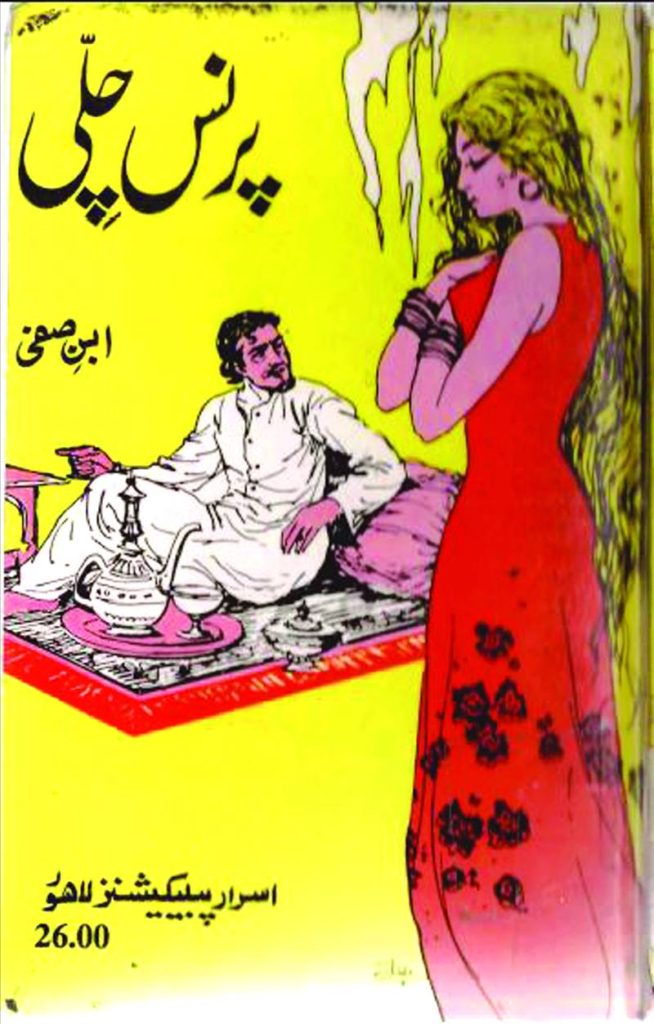

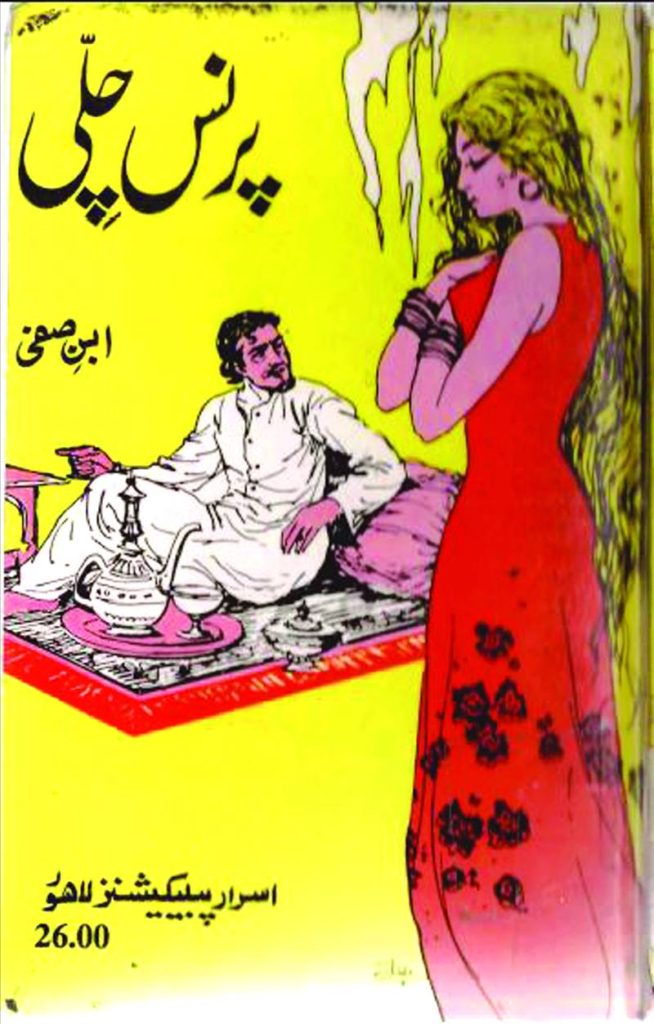

So our eponymous hero uncritically accepts Raees as the leader in return for the benefits of patronage. One such benefit was his introduction to a tavaif tastefully named Haqiqat (Reality). At their first meeting at her kotha, she asks him to visit her often, so much so that he falls in love with her. So, Raees drives him away from Reality and into the arms of another patron, Sir Fayyaz. As part of the new arrangement, Prince Chilli is required to cultivate his new patron by excessively praising him for his chess moves at the exclusive Fairies Wing Club. An invitation to the birthday party of Sir Fayyaz’s daughter Shahida sets up a third avenue of patronage for Chilli. He begins to fall in love with Shahida and learns the art of buttering up her father by intentionally losing to him at the many chess sessions they have at the Fayyaz home.

Meanwhile Raees himself is shown to be dealing with a revolt in his own ranks – a reference to the inter-union violence among students in the Pakistan of the 1950s. On at least two occasions, he is asked by the Prince as to why the former is so kind and indulgent towards the latter. On the first occasion, he says that social service was his motto; on the second occasion he is a bit more specific and personal in that he “wants to defeat headstrong parents.” Could these headstrong parents be a metaphor of the so-called paternalistic Pakistani state under Ayub Khan?

Unlike his failed love affair with ‘Reality’, Raees actively encourages Chilli’s love affair with Shahida. Shahida also confesses her love for Chilli. Sir Fayyaz is also very happy with this development, but only until he finds out that our hero has been disinherited by his parents. So he tells Chilli not to come to his house again.

After a hastily organized marriage – which as the reader finds out could not have been possible without the intervention of the Interior Minister - and eventual acceptance by Shahida’s father, the novel moves forward after Raees sensationally admits to Chilli that Shahida was once betrothed to the former in childhood.

Our hero is now ready to be exploited once again not only by his wife but by her sympathetic cousin Naheed who has ‘revolutionary ideas’ and like his benefactor Raees, is hell-bent on avenging selfish old men, in this case Chilli’s father-in-law, Sir Fayyaz. It also transpires that our hero is a cog in his wife’s scheme of being the leader of a group of strong and healthy women who will eventually kidnap men from the street on their jeep. He will serve as a guinea pig in this scheme.

A true comedy of errors ensues as Chilli flits from one patron to another; from would-be ‘comrades’ – while torn between Shahida and Naheed – back to Chacha Raees, who apparently is ready with another plan for his beloved nephew: a sensational escape to idyllic Rajgarh, where he would be staying with a mystery partner in a hotel room, before being ‘rescued’ by a blonde femme fatale called Sonia who then conveniently disappears after depositing him in another dreamy place, ‘far across the horizon’, only to be accosted by the police on the charges of cocaine-smuggling and put in jail. Meanwhile Shahida has been bought round to her husband’s side by a sympathetic housekeeper. Once again the good offices of Raees ensure that Prince Chilli is swiftly brought out of jail and onto a comfortable retirement to domestic life with Shahida.

Some of the political and cultural references in Prince Chilli refer to later developments in Pakistan following the ouster of Ayub Khan by a powerful student movement across Pakistan. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had by now become the darling of the NSF after the Indo-Pak war of 1965 and his public break with Ayub Khan; even the pro-government MSF began to support Bhutto. The 1970s became the golden era of student politics in Pakistan, though unlike the 1960s, the student movement would never be able to topple another Pakistani ruler; clashes between the leftist NSF and fundamentalist IJT leading to bloody attacks and reprisals and slandering campaigns were common before the 1970 elections, including street fighting. These are alluded to briefly in the novel, especially in the scene where Chilli is visiting Naheed after being dejected with Shahida’s attitude, and Shahida and her friends reach Naheed’s home armed with small axes to teach both of them a lesson.

When Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party ascended to power after the 1970 elections, it created its own loyalist student union the Peoples Student Federation to control campus politics and counter the NSF. After 1974, there was another challenge to the PSF in the form of the Sindhi nationalist Jiye Sindh Students Federation. Between 1970 and 1977 – the year Prince Chilli was written – student unionism was rife in Pakistan, there were regular student elections and students’ issues were democratically addressed. It was only after 1977, that the PSF produced a stalwart student leader in the form of Salamullah Tipu, under whose leadership armed pitched battles were fought with the resurgent IJT in Karachi campuses and democratic activism gave way to violence and gun-running. Tipu himself had a violent end some years later in Kabul while on the run from police, a victim of the politics of patronage amongst IJT, which he initially joined, then the NSF and finally the PSF. It is tempting to compare the fictional Raees and Prince Chilli with the real-life Tipu, but Raees was too much ensconced within the government and Chilli with his wife for them to end up like Tipu!

Safi may not have seen the rise of the likes of Tipu but the astute social critic and humourist that he was, in the novel itself he poked fun at the opportunism in the ranks of the socialists within the student unions and made a light critique on the contradictions within Bhutto’s party, which led to his overthrow in July 1977:

“‘Easier said than done. Look at me…I am the real socialist.’

‘Meaning…’

‘The matters of the beard and marriage are nonsense. Actually I had raised a voice against injustice to peasants so I have been disinherited…after all what is left in a beard and marriage.’

‘Ss…so…you are socialist.’

Chilli thought what harm is there in saying “yes” when gradually all the feudals and capitalists are becoming socialist.

‘Yes. I am socialist.’

‘Then why did you marry Shahida.’

‘So that iron can cut iron. Like you I also want that these classes should become extinct by fighting among them indeed…did Shahida show you that letter, which my abba huzoor has written to Sir Fayyaz.’

‘Yes she showed us.’

‘I have made two landlords fight in this way. Soon abba huzoor will send an army of two, two-and-a-half dozen rustics here, which will destroy Sir Fayyaz’s mansion.’

‘Really’, the eyes of that girl started shining.

‘Yes comrade.’

‘Then you are indeed from among us.’”

There are other social and cultural changes which Safi chronicles in Prince Chilli. Most of these changes took place with the ushering in of the Bhutto government. A more liberal atmosphere exemplified by cafes like the Fairies Wing Club in the novel; class conflict as highlighted by the romance between scions of the rural classes like Chilli and women of the upper class like Shahida and Naheed; and conflicts between the hereditary rich (like Naheed) and the newly-rich (like Shahida); the independent and outspoken streak of Pakistani women, rebelling against their parents by getting involved and marrying middle or lower-class men, viz. the effects of ‘Women’s Lib’ and its effects on Pakistani society. The reader remembers that Shahida’s father tried to sabotage her marriage to Chilli by disapproving of him, forcing her to move out of her father’s home eventually. Another interesting matter merely alluded to in the novel but which had grown among college and university students in 1970s Pakistan was the use of hashish; in the novel the Rajgarh police try to unsuccessfully implicate first Raees and the his protégé Chilli for cocaine smuggling. Then the hippie culture of the time is manifested in the form of the decision of Chillie to shave off his beard, as well as the rise of goondaism in the streets over ideology as was actually happening on Pakistani streets, and over women as depicted in Prince Chilli. One can argue that Safi’s novel comes as close to depicting this populist-liberalism of the 1970s as some of the superhit Pakistani films of that period like Samaj and Aaina.

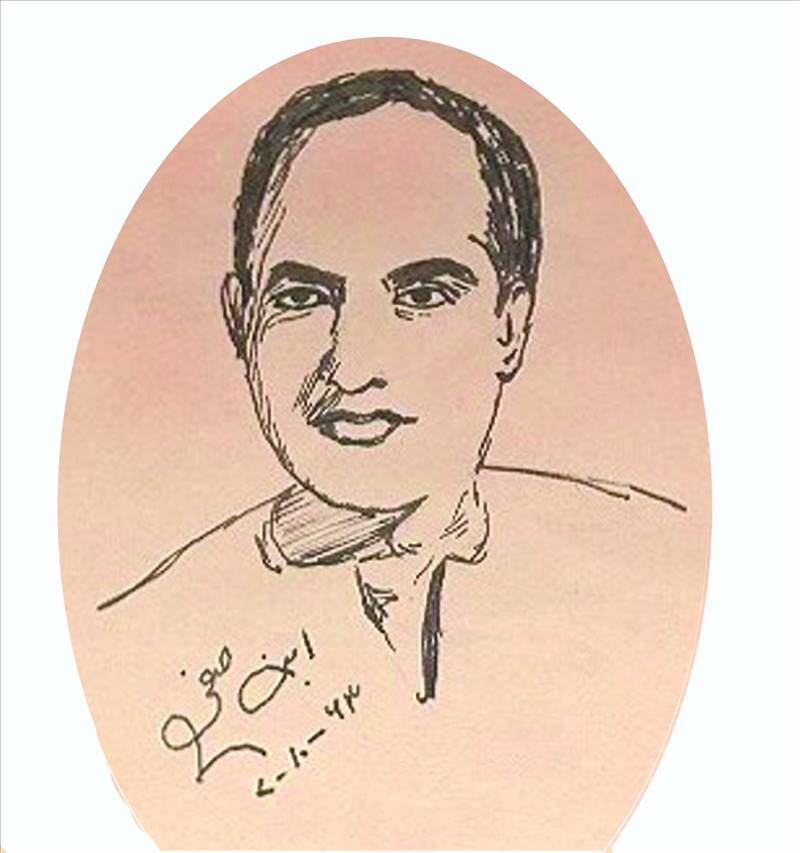

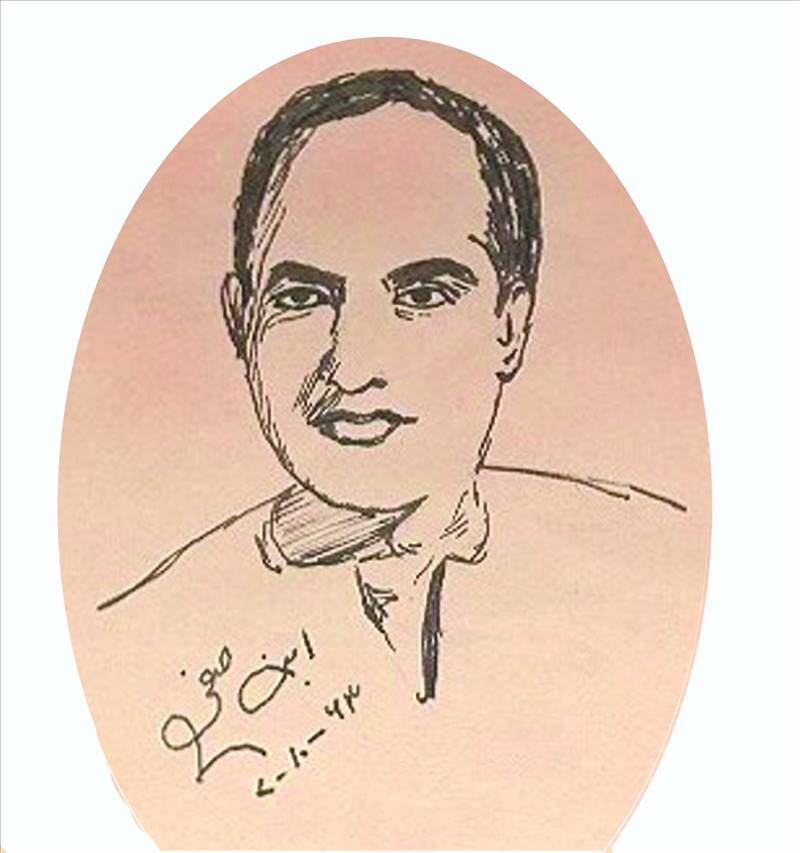

It is thus a huge pity that Ibne Safi is known more in our midst for his bestselling detective novels than for his poetry or social satire. In Prince Chilli, he identified a national condition that was and is still as symbolic of Pakistan as Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov was of 19th century Russia and Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui was of the rise of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party in pre-WW2 Germany. Forty years on from Safi’s death and on the second anniversary of the elections that voted in Imran Khan’s Naya Pakistan as I write this, he deserves our gratitude and appreciation for daring to interpret our national maladies with sparkling wit that is as instructive and relevant as it is entertaining.

All translations from Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

So our eponymous hero uncritically accepts Raees as the leader in return for the benefits of patronage. One such benefit was his introduction to a tavaif tastefully named Haqiqat (Reality). At their first meeting at her kotha, she asks him to visit her often, so much so that he falls in love with her. So, Raees drives him away from Reality and into the arms of another patron, Sir Fayyaz. As part of the new arrangement, Prince Chilli is required to cultivate his new patron by excessively praising him for his chess moves at the exclusive Fairies Wing Club. An invitation to the birthday party of Sir Fayyaz’s daughter Shahida sets up a third avenue of patronage for Chilli. He begins to fall in love with Shahida and learns the art of buttering up her father by intentionally losing to him at the many chess sessions they have at the Fayyaz home.

Meanwhile Raees himself is shown to be dealing with a revolt in his own ranks – a reference to the inter-union violence among students in the Pakistan of the 1950s. On at least two occasions, he is asked by the Prince as to why the former is so kind and indulgent towards the latter. On the first occasion, he says that social service was his motto; on the second occasion he is a bit more specific and personal in that he “wants to defeat headstrong parents.” Could these headstrong parents be a metaphor of the so-called paternalistic Pakistani state under Ayub Khan?

Unlike his failed love affair with ‘Reality’, Raees actively encourages Chilli’s love affair with Shahida. Shahida also confesses her love for Chilli. Sir Fayyaz is also very happy with this development, but only until he finds out that our hero has been disinherited by his parents. So he tells Chilli not to come to his house again.

After a hastily organized marriage – which as the reader finds out could not have been possible without the intervention of the Interior Minister - and eventual acceptance by Shahida’s father, the novel moves forward after Raees sensationally admits to Chilli that Shahida was once betrothed to the former in childhood.

One can argue that Safi’s novel comes as close to depicting this populist-liberalism of the 1970s as some of the superhit Pakistani films of that period like Samaj and Aaina

Our hero is now ready to be exploited once again not only by his wife but by her sympathetic cousin Naheed who has ‘revolutionary ideas’ and like his benefactor Raees, is hell-bent on avenging selfish old men, in this case Chilli’s father-in-law, Sir Fayyaz. It also transpires that our hero is a cog in his wife’s scheme of being the leader of a group of strong and healthy women who will eventually kidnap men from the street on their jeep. He will serve as a guinea pig in this scheme.

A true comedy of errors ensues as Chilli flits from one patron to another; from would-be ‘comrades’ – while torn between Shahida and Naheed – back to Chacha Raees, who apparently is ready with another plan for his beloved nephew: a sensational escape to idyllic Rajgarh, where he would be staying with a mystery partner in a hotel room, before being ‘rescued’ by a blonde femme fatale called Sonia who then conveniently disappears after depositing him in another dreamy place, ‘far across the horizon’, only to be accosted by the police on the charges of cocaine-smuggling and put in jail. Meanwhile Shahida has been bought round to her husband’s side by a sympathetic housekeeper. Once again the good offices of Raees ensure that Prince Chilli is swiftly brought out of jail and onto a comfortable retirement to domestic life with Shahida.

Some of the political and cultural references in Prince Chilli refer to later developments in Pakistan following the ouster of Ayub Khan by a powerful student movement across Pakistan. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had by now become the darling of the NSF after the Indo-Pak war of 1965 and his public break with Ayub Khan; even the pro-government MSF began to support Bhutto. The 1970s became the golden era of student politics in Pakistan, though unlike the 1960s, the student movement would never be able to topple another Pakistani ruler; clashes between the leftist NSF and fundamentalist IJT leading to bloody attacks and reprisals and slandering campaigns were common before the 1970 elections, including street fighting. These are alluded to briefly in the novel, especially in the scene where Chilli is visiting Naheed after being dejected with Shahida’s attitude, and Shahida and her friends reach Naheed’s home armed with small axes to teach both of them a lesson.

When Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party ascended to power after the 1970 elections, it created its own loyalist student union the Peoples Student Federation to control campus politics and counter the NSF. After 1974, there was another challenge to the PSF in the form of the Sindhi nationalist Jiye Sindh Students Federation. Between 1970 and 1977 – the year Prince Chilli was written – student unionism was rife in Pakistan, there were regular student elections and students’ issues were democratically addressed. It was only after 1977, that the PSF produced a stalwart student leader in the form of Salamullah Tipu, under whose leadership armed pitched battles were fought with the resurgent IJT in Karachi campuses and democratic activism gave way to violence and gun-running. Tipu himself had a violent end some years later in Kabul while on the run from police, a victim of the politics of patronage amongst IJT, which he initially joined, then the NSF and finally the PSF. It is tempting to compare the fictional Raees and Prince Chilli with the real-life Tipu, but Raees was too much ensconced within the government and Chilli with his wife for them to end up like Tipu!

Some of the political and cultural references in Prince Chilli refer to later developments in Pakistan following the ouster of Ayub Khan by a powerful student movement

Safi may not have seen the rise of the likes of Tipu but the astute social critic and humourist that he was, in the novel itself he poked fun at the opportunism in the ranks of the socialists within the student unions and made a light critique on the contradictions within Bhutto’s party, which led to his overthrow in July 1977:

“‘Easier said than done. Look at me…I am the real socialist.’

‘Meaning…’

‘The matters of the beard and marriage are nonsense. Actually I had raised a voice against injustice to peasants so I have been disinherited…after all what is left in a beard and marriage.’

‘Ss…so…you are socialist.’

Chilli thought what harm is there in saying “yes” when gradually all the feudals and capitalists are becoming socialist.

‘Yes. I am socialist.’

‘Then why did you marry Shahida.’

‘So that iron can cut iron. Like you I also want that these classes should become extinct by fighting among them indeed…did Shahida show you that letter, which my abba huzoor has written to Sir Fayyaz.’

‘Yes she showed us.’

‘I have made two landlords fight in this way. Soon abba huzoor will send an army of two, two-and-a-half dozen rustics here, which will destroy Sir Fayyaz’s mansion.’

‘Really’, the eyes of that girl started shining.

‘Yes comrade.’

‘Then you are indeed from among us.’”

There are other social and cultural changes which Safi chronicles in Prince Chilli. Most of these changes took place with the ushering in of the Bhutto government. A more liberal atmosphere exemplified by cafes like the Fairies Wing Club in the novel; class conflict as highlighted by the romance between scions of the rural classes like Chilli and women of the upper class like Shahida and Naheed; and conflicts between the hereditary rich (like Naheed) and the newly-rich (like Shahida); the independent and outspoken streak of Pakistani women, rebelling against their parents by getting involved and marrying middle or lower-class men, viz. the effects of ‘Women’s Lib’ and its effects on Pakistani society. The reader remembers that Shahida’s father tried to sabotage her marriage to Chilli by disapproving of him, forcing her to move out of her father’s home eventually. Another interesting matter merely alluded to in the novel but which had grown among college and university students in 1970s Pakistan was the use of hashish; in the novel the Rajgarh police try to unsuccessfully implicate first Raees and the his protégé Chilli for cocaine smuggling. Then the hippie culture of the time is manifested in the form of the decision of Chillie to shave off his beard, as well as the rise of goondaism in the streets over ideology as was actually happening on Pakistani streets, and over women as depicted in Prince Chilli. One can argue that Safi’s novel comes as close to depicting this populist-liberalism of the 1970s as some of the superhit Pakistani films of that period like Samaj and Aaina.

It is thus a huge pity that Ibne Safi is known more in our midst for his bestselling detective novels than for his poetry or social satire. In Prince Chilli, he identified a national condition that was and is still as symbolic of Pakistan as Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov was of 19th century Russia and Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui was of the rise of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party in pre-WW2 Germany. Forty years on from Safi’s death and on the second anniversary of the elections that voted in Imran Khan’s Naya Pakistan as I write this, he deserves our gratitude and appreciation for daring to interpret our national maladies with sparkling wit that is as instructive and relevant as it is entertaining.

All translations from Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com