My curiosity about Bukhara in particular, and a desire to visit it started from hearing about the origins of my family from Bukhara since childhood. Then, much later in life I came across two comments made by my late grandfather, Professor Ahmed Shah Bokhari (Patras).

One was in an interview of him, published in The New York Times Magazine on March 15, 1953. The other in a letter from him to my father dated August 13, 1956. My grandfather passed away in New York on December 5 1958.

In the NYT interview my grandfather mentioned attempting to take a journey (as an escape from Peshawar as a 10-year old in 1908) with a caravan returning to Central Asia or Turkestan as the region was called at the time. From the publication, it seems he attempted this more than once, each time unsuccessfully. Then again, he reminisces about Turkestan in his letter to my father dated August 13 1956. From family accounts it is clear that he never managed to visit Turkestan, his ancestral homeland as he remained busy with his duties as a senior official at the United Nations, based in New York, till he passed away in 1958. Excerpts from these two sources are reproduced at the end of this note.

This forms the backdrop to my visit to Uzbekistan as it is now called. It was formerly a part of Turkestan. My visit there from April 27 2023 to May 5 2023 came some 115 years after my grandfather’s earliest expressed desire and attempts as a 10-year old in 1908.

A few hours after I arrived in Uzbekistan’s capital city Tashkent, I joined a Pakistani businessman friend at a dinner hosted by him. He had extended the dinner invitation to me a few days earlier as he knew that my visit to Tashkent would overlap for that evening with his. He was entertaining two senior local government officials.

I couldn’t help but notice how they both took a double take as soon as I was introduced by my surname “Bokhari”. This was followed by a more than normal respectful handshake, and I could detect a certain respect in their eyes, followed by a slightly exaggerated bowing of their heads towards me out of respect. My host and his three Pakistani colleagues also noticed this. This was my first interaction with any persons in Uzbekistan.

My visit to Uzbekistan continued for the next six days to Tashkent (current capital of Uzbekistan), Samarqand (capital of the Timurid and other empires), Shehr-e-Sabz (birthplace of Amir Temur) and Bukhara (capital of the Khanate of Bukhara). At each place, whenever I was introduced to anyone with my surname in any of these cities, I continued to be greeted with a double take, a pause, a respectful look and warm handshake. Some people also greeted me with the following words:

“Welcome home” “You are one of us” “This is your country”

“You must visit more often”

“Why didn’t you bring your family? You must bring them next time”

This greeting was more pronounced and warmer by people in the city of Bukhara where I spent two days, than in Samarqand, where I spent three days.

My family is said to have migrated from Bukhara around the turn of the century in either late 1700s or early 1800s. I am given to understand that they first moved to Kashmir and then settled in Peshawar around the mid-1800s. They were seeped in the traditions of Sufis and their first language was Persian. Other languages were acquired to assimilate with the local people.

Brief Historical Perspective:

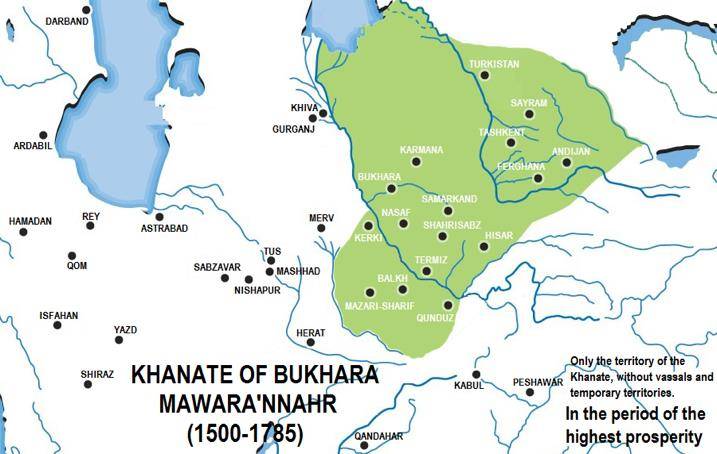

The Russians had started making inroads to parts of Central Asia around the late 18th century. The Russian conquest of Central Asia took place over several decades. In 1839, Russia failed to conquer the Khanate of Khiva, south of the Aral Sea. In 1847–53, the Russians built a line of forts from the north side of the Aral Sea eastward up the Syr Darya river. The Khanate / Emirate of Bukhara was adjacent to the east of the Khanate of Khiva. Today, Khiva and Bukhara are a part of Uzbekistan and cease to be “Khanates” or “Emirates”, as they used to be called.

Most Central Asian states and people had begun to feel the growing Russian interest and influence in the late 18th century. This was not welcomed, but the Central Asian rulers were subjugated by the power of the Russians. Those people who could leave, migrated to different parts of the world. I believe my ancestors were among those who emigrated. The easiest exit route to take was the centuries old Silk Road in to India and other parts, most likely with the caravans traveling these routes.

There are a number of reasons why the Russians wanted to move southward into Central Asia. First, there was an economic reason, that is, to create markets for Russian goods. This motive became even more acute in 1860s as a result of the U.S. Civil War, when the south was isolated and cotton was in short supply.

By the 19th century, Central Asia was completely taken over by Russia. In 1868, the Russians moved into Tashkent and made the city their capital in Central Asia. Many of the independent “Khanates” or “Emirates” were either conquered or operating under Russian protection.

The conquest of Central Asia was completed by the Bolsheviks which came at the end of World War 1. The Bolsheviks mounted a military attack (“Battle of Bukhara”) on the Emirate of Bukhara in 1920. This involved dropping 200 bombs on the Ark Citadel (the Ruler’s Fort) in the heart of Bukhara city, said to have been built some 3,000 years ago by a Persian Prince Siyawush, and used by whoever ruled Bukhara over the next centuries. The fort is said to have been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. The last destruction in 1920 left 90% of the fort in ruins as the last Emir of Bukhara, Sayyid Mir Muhammad Alim Khan (1880-1944) fled to Afghanistan with his valuables and blew up the Harem to prevent it from being desecrated by the Bolsheviks. He died in exile in Afghanistan.

The age of the Ark Citadel has not been established accurately, but by 500 CE it was already the residence of local rulers. Here, in the fastness of the citadel (it is slightly elevated with very high and thick walls surrounding it), lived the emirs, their chief viziers, military leaders, and numerous servants.

When the soldiers of Genghis Khan took Bukhara in the 13th century A.D., the inhabitants of the city found refuge in the Ark, but the conquerors smashed the defenders and ransacked the fortress.

In the Middle Ages the fortress was worked on by poets, scientists & philosophers such as Rudaki, Ferdowsi, Avicenna, Farabi, and later Omar Khayyám. Here also was kept a great library, of which Avicenna wrote:

“I found in this library such books, about which I had not known and which I had never before seen in my life. I read them, and I came to know each scientist and each science. Before me lay gates of inspiration into great depths of knowledge which I had not surmised to exist.”

Most probably, the library was destroyed following one of the conquests of Bukhara.

Today, in the year 2023, Uzbekistan’s population is 36 million, of which 88% are Muslims. The country attracts 6-7 million tourists per year and this is poised to grow as the world discovers this hidden gem of Central Asia. Its capital city is Tashkent (pop. 3.0m) and key cities are Samarqand (population 0.5 million) and Bukhara (population 0.3 million).

Uzbekistan’s history has roots going back 3-5,000 years, starting from the Persian Empire, The Ancient Silk Road (started in 123 B.C.) with links to China, Persia, Western and South Asia, the coming of the Arabs and spread of Islam, the Mongols, the Timurid Dynasty, the Khanate and later Emirate of Bukhara, influence of Russians and eventually the Bolsheviks in the 18th & 19th centuries culminating in its takeover by USSR in 1920. All this happened in this small part of the world.

Upon attaining its independence from the USSR in1991, a process of rediscovery and reconstruction of the roots of the Uzbek people has been put in motion in in earnest. The Timurid Dynasty founded by Amir Temur (1336-1405) is projected with great pride. It is a pity that western historians have chosen to call Amir Temur very unkindly by the name “Temerlane” or “Temur the Lame”. His was one of the largest empires in the world during his time, where he never lost a battle!

There is a need to present a more balanced view of Amir Temur instead of just the brutal image projected. His contribution towards the promotion of Islam and learning is something which the Uzbekistan people are very proud of and their government is trying to familiarize the world with it. Similarly, his successor and grandson, Ulugh Beg’s contribution to Astronomy, Mathematics and scholarly contributions is world renowned and could do with greater projection.

Today, some 32 years after independence, we see a massive effort towards the restoration and renovation of historic monuments, re-positioning their heroes, re-introducing their language (from the mandatory Russian language to reverting to “Uzbek”, which is very close to the Tajik language and a Persian dialect, actively familiarizing their younger generation with their Islamic history and culture. I saw hundreds of school children being given tours to historical monuments, madrassas, mosques and museums every day. The country is predominantly Muslim (88% of the population), and the same time remains secular.

The mix of races and religion is reflected in the physical features of the Uzbek people, their cultural practices, the architecture, their dress, language and ethos, which embraces all the cultural influences they have absorbed over the last 3-5,000 years. One can detect a strong Persian influence in the Uzbek language due to several centuries of Persian rule, presence of Persian speaking scholars and poets, and proximity to Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Iran.

Samarqand served as the capital of various Empires with Bukhara never far behind as a center of learning and spirituality.

Learning, and respect for it is amply demonstrated through the numerous Madrassas where subjects taught as far back as the 8-14th Century A.D. included Astronomy, Mathematics, Medicine, Religion, Sufi-ism, Philosophy, and several others. It’s no coincidence that medicine finds its roots in Bukhara through the works of Abu Ali Ibn Sina (aka Avecinna), with a Medical University named after him in Bukhara.

Some prominent persons associated with Bukhara and Samarqand are:

- Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari (810-870 A.D.) commonly referred to as Imām al-Bukhāri or Imām Bukhāri, was a 9th-century Muslim Muhaddith who is widely regarded as the most important hadith scholar in the history of Sunni Islam.

- Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn bin ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Ḥasan bin ʿAlī bin Sīnā al-Balkhi al-Bukhari (980-1037 A.D.) commonly known in the West as Avicenna from Bukhara. He was a polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic Golden Age and the father of early modern medicine.

- Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khawarizmi (780-850 A.D.): from Khwarazm, some 400km from Bukhara. He lived in Baghdad under the 7th Abbasid Caliph Ma-mun Ibn Ar-rashid. Astronomer, mathematician, and considered the founder of Algebra. The word “Algebra” comes from the title of his book “Al-jebr” meaning “completion” or “rejoining”.

- Maulana Jalal-ud-Din Rumi (1207-1273 A.D.), famed Turkish Islamic scholar, sufi mystic and poet, originally from Iran, who spent the early years of his life in Samarqand and also taught at the Madrassa in Registon in Samarqand.

- Syed Jalaluddin Shah “Surkh-Posh” Bukhari (1199-1295), a Sufi saint, who travelled from Bukhara to Multan to preach Islam and is buried in Uch Sharif near Multan, Pakistan. He was a descendant of Imam Hussain (A.S.), a grandson of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). The Family Tree provided to me by my relatives from Peshawar shows my family to descend from his line.

- Bahauddin Naqshband Bukhari (1318-1389). He was born in the village of Hinduvan, around 10 km from the city of Bukhara, and is buried there. He is founder of one of the largest Sufi Sunni orders, the Naqshbandi Order which is followed in numerous countries including South Asia, Syria, Egypt, China and others.

The Masjid-i-Jehan-Numa commonly known as the Jama Masjid of Delhi is one of the largest mosques in India. It was built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jehan between 1650 and 1656, and inaugurated by its first Imam Syed Abdul Ghafoor Shah Bukhari who was especially invited from Bukhara for this purpose. The family never returned to Bukhara, and descendants of the “Bukhari” family continue to be the Imams of the mosque to this day.

Excerpt from the New York Times Interview and a letter to my father:

“Peshawar, Bokhari's home town, is the capital of the North-West Frontier Province, once India's, now Pakistan's. When life got too difficult for a l0-year old to handle, Bokhari had an outlet - the Peshawar equivalent of running away with the circus, namely, tagging along with the next dawn departure of a caravan bound for Central Asia. The arm of the law and parental authority usually caught up with Bokhari at the Khyber Pass, about a dozen miles from Peshawar. "When I got home, I used to get a cool but warm reception," he remembers.”

- by A.M. Rosenthal, UN Correspondent, The New York Times. The New York Times Magazine, March 15 1953.

“More and more my wakeful and sleeping dreams are about Peshawar. My childhood, I realize now, was full of magic and new mental discoveries almost each day. How I wish I could go back to Peshawar. Alas, perhaps now I never shall. Even if I do, adulthood and its social obligations will keep hidden from my eyes the fairy-land that it was. How will I ever be able to walk the dusty road outside Kohati Gate and make my way to blossoming orchards heavy with dew; or smell the roasted meat in shops and eating-houses full of strange travelers from the heart of Asia; or stand in the crisp cold wind from the snow-peaked hills; or roam around the Saddar (town center), contacting far-off England through second-hand detective magazines, or the smell of candy, biscuits and toilet soap that made up a "European" shop like Gai's……and so on……while in counter point ran my reading: Kipling and "Little Lord Fauntleroy" and the diwans of ghazal-writers with which our house was full, and debates about the interpretation of the Quran and the cool water in the pool of the mosque of Shah Wali Qattal. Sikandar Bhaijan was a moharrir in the Octroi department. He was posted at one city gate or another checking and assessing the imports and I sat with him through the hot summer afternoons. But the Ghaz trees swayed overhead and the water from the earthen kuza was always sweet and cool, and the kabab and roti was delicious and the merchandise from the hills on camels and donkeys and mules was strange and varied and joined Turkestan to us by routes that we had never seen. Late in the afternoon would arrive bundles of snow wrapped up in rushes, collected by the folks in the hills during the winter to be sucked by the falooda-drinkers in the town in the summer….how can I see and flavour all this again?”

Letter from Father to Son – Ahmed Shah Bokhari to Syed Haroon Bokhari August 13, 1956

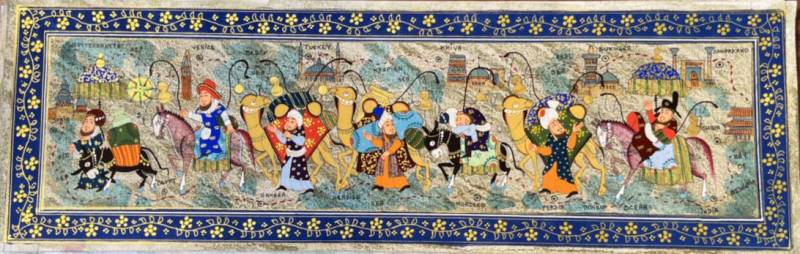

The Silk Road routes of the caravan

From China, to Samarqand, Bukhara, Khiva, Aral Sea, Caspian Sea, Turkey, Black Sea, Venice, Mediterranean Sea, Spain, Morocco,, Sahara, Egypt, Red Sea, Persia,, Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, India and back to the Bay of Bengal. A local to Bukhara artist’s depiction below:

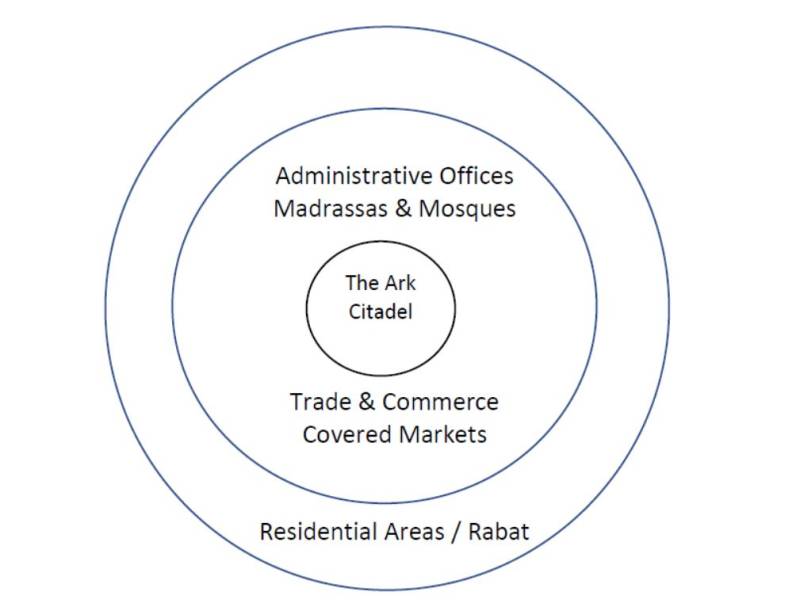

Layout of the City of Bukhara:

Like most ancient cities, the city of Bukhara was also a walled city.

The city of Bukhara could be described as being in three sections:

Section 1: The Ark Citadel – the Ruler’s Fort

Section 2: Center for administration, learning, praying, trade & commerce.

Section 3: Residential

Section 1:

The Ark Citadel – Ruler’s Fort, housing formal meeting areas, mosque, offices, residences for selected personnel & their and the ruler’s family, etc. The inner core of the city was the Ark Citadel, of the fort of the rulers of Bukhara. Here resided the ruler, his family and his cabinet of ministers. The fort was like a small city in itself which accommodated some 3,000 people.

Section 2:

Outside the Ark Citadel were two areas, each walled. The first walled area comprised of four main types of activities:

- Government administrative offices

- Places of Learning - Madrassas

- Places of Worship - Mosques

- Trade & Commerce – production facilities of handicrafts and shops of traders, and eateries. The more affluent were privileged to have their homes within this area in what were and still are called ‘Mohallas”. A small Caravan Sarai’s for the more affluent.

Section 3:

Outside the first walled area was another walled area called “Rabat”, an Arabic word originating from “er-Ribat” meaning the Islamic base or fortification. This was apparently a mainly residential area of the inhabitants of the city. This too was a walled area, which formed the outer most wall of Bukhara city.

It is said that the outer wall of the city had 11 gates (much like so many other old cities - Peshawar had 16, Lahore had 13, Delhi had 14, and so on).

Over time and as a consequence of various invasions, both the outer and inner walls of the city have been completely destroyed. A small section of a replica of the outer wall has been built to illustrate the heritage of the city.

Outside the “Rabat” were caravan Sarais which also included “Hamams” (baths) for the weary travellers to reside and refresh and cleanse themselves before entering the city for trade and commerce.

Significance of pursuit of Learning and Spirituality:

Madrassas formed the major centers of learning throughout the region, and for centuries there has been a strong tradition of pursuit of learning, not just of Islamic values and virtues, but of science, mathematics, poetry, philosophy, astronomy, etc. There are numerous examples of rulers and noblemen who constructed special tombs for their teachers and lie buried at their feet. It is significant to note that many rulers of Bukhara and Samarqand (including Amir Temur himself) are buried at the feet of the graves of their teachers out of respect for them, mostly by their own choice. Whilst they exercised worldly power and wealth, they did not fail to respect the learned. This ethos remains instilled in the people even today.

The 70 years of Communist rule promoted “Atheism” and religion was not allowed to be practiced – neither Zoroastrianism, nor Judaism, nor Christianity, nor Islam. Yet, we find today that 88% of the population are Muslims, as Islam became the dominant religion with the spread of Arab and Persian rule commencing from the eighth century A.D. The practice of religion is widespread and resurgent, and it is a secular country. Original manuscripts of the Quran from the seventh Century A.D. onwards are on display in museums.

For me personally, the trip was a highly emotional and fulfilling experience. A significant part of me was always anchored to Peshawar. Now Bukhara as well. May everyone have the good fortune to achieve their childhood dreams!

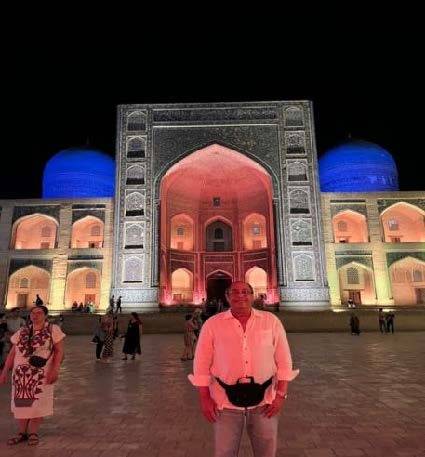

Some pictures to give a flavor of Bukhara:

Bukhara is 270 km to the west of Samarqand. As one travels to Bukhara there are numerous grape vines and orchards along the way with fresh cherries and apricots being sold on the roadside by farmers. Samarqand and its surrounds have fertileland and the land turns somewhat arid beforereaching the oasiscity of Bukhara. Beyond Bukhara and towards Khiva the terrain turns into a desert before reaching the Aral Sea.

The entrance to the city of Bukhara from Samarqand. Bukhara is written as “Buxoro” where “x” is pronounced as “kh” and “o” as “a”.

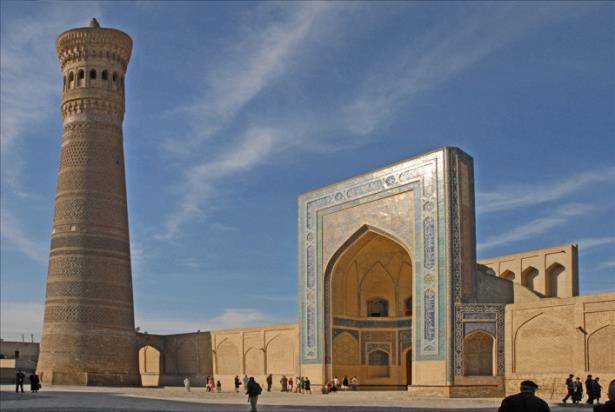

It is a part of the Poi-Kalon ensemble and is located on the Kosh* principle opposite the Miri-Arab Madrasah. Mosques started to be built in Bukhara soon after the Arab invasion in 709. The first mosque was built in 712, on the territory of the Ark citadel. With the subsequent Islamization of the population, this mosque became too small; a new, more prominent mosque was built outside the fortress in 770. In the 10th century, this mosque collapsed during Friday prayers: countless people died so that the streets of Bukhara seemed empty. As a result, the mosque was rebuilt and destroyed several times, whether due to wars, fire or mistakes in construction.

*The Kosh Principle: in classical Central Asian architecture two buildings located on the same axis and facing opposite each other.

Therefore, in the 12th century, a new big mosque was built by the ruler Arslan-khan, next to it – the Kalon minaret. This mosque existed until the Mongol invasionin1220whenthe minaret was preserved and conquerors burned down the mosque. It is rumoured that Genghis Khan considered the mosque a palace of the ruling family because of its size, which he ordered to destroy. As a result, the ruins remained untouched for over 200years. It was the time of the Timurids (14-15 c.) that the construction of a new mosque began, but it is impossible to trace the extent of the work done. The structure was finished only in the 16th century during the subsequent rulers, Sheybanids. But it shows elements typical of Timurid architecture.

The external dimensions of the Kalon Mosque are about 127 by 78 meters, which is about by a quarter more minor than the Bibi-Khanum Mosque in Samarkand, built by Amir Temur. Nevertheless, the mosque could accommodate up to 10,000 people. The inner courtyard is about 78 by 39 meters, built in a 2:1 ratio. The inner courtyard is surrounded by an arched gallery covered with a roof consisting of 288 saucer domes, only visible from above. Two hundred eight columns support the arched gallery. The decoration consists of various geometric and vegetal designs on majolica, mosaic and glazed terracotta.

Note:

This article comprises of only some brief personal reflections around Bukhara. The entire area of Central Asia has a rich history, which merits a much deeper study to better understand the influence of the region on not just Central Asia, but also Arabia and South Asia and other parts of world and world history.