Danish Bashir graduated with BA Honours in Philosophy from FC College, Lahore. He writes short stories, is an avid reader and enjoys good film. His passions include old architectures, geometric patterns and calligraphy. He is currently teaching “Fundamentals of Geometry as Art” at Hast o Neest.

Jamile Naqi: We know so little of Balochistan. And we often hear only of troubles. What is the culture of Baloch people, in your view?

Danish Bashir: A certain view of “ghairat”, critical to Baloch identity, is a moral value that guides Baloch and they strive to live up to its code of conduct. Under the umbrella of ghairat are:

‘Insaan Dosti’ (friendship): Each person’s self (ego) is as important as the next person’s. No one must be put down. Similarly, we respect our own self and don’t allow it to be diminished. ‘Insaan Dosti’ is present in our dealings with each other (without our being aware of it.)

Our ‘zabaan’ (word) must be honoured.

Hospitality is central to us and even if our enemy seeks ‘panaa’ (shelter) with us, we are compelled by conscience to provide it.

We love our homeland. A Baloch who migrates is looked down upon and is called a ‘bhagora’ (runaway).

Honourable faithfulness, providing service and a helping hand - these are Baloch ideals. Atta Shad, a nationalist Balochi poet, expresses it as follows:

The price of the bowl of water in my land is enduring loyalty

Let’s quench our thirst and repay with ardent faithfulness

J.N.: What can you tell us about the famed Baloch fighting spirit?

D.B.: In geographical terms, Balochistan borders Iran, Afghanistan and Sindh. Baloch history is one of conflicts, wars and migrations. Migrations took place along the trade routes of Iran, Afghanistan and Sindh - and kings and warlords fought to crush the migrants. At times, Baloch had no option but to resort to being bandits and mercenaries in order to survive. The land is barren and people cannot live off it so easily.

Rugged mountainous terrain, harsh climate and conflicts led to a turbulent “no-frills” life. Personal disputes and friction between tribes could at times lead to feuds that went on for decades.

Balach Gorgej, an 18th century poet, pens the heroic, simple life and fighting spirit of the Baloch:

Gwat (Air)

“The mountains are the Baloch forts

Their companions the trackless cliffs

The lofty heights are (their) gwatg

Their water are the flowing springs

Their cups are made of dwarf-palm leaves

Their sitting places are thorny bushes

Their mattresses are bedsteads on the ground.

Their mounts are white leather sandals

Their sons are chosen arrows

their sons-in-law are pointed daggers

Their brothers are solid-rock spears

Their venerable (fathers) great-wounding scimitars”

J.N.: How and when did a cycle of revenge killings stop?

D.B.:There came a point when both sides were exhausted and a midh (peace) was undertaken: womenfolk take off their shawls and place them at the feet of their enemy’s patriarch, pleading,

“For God’s sake, we do not have enough menfolk left to fight. Let’s stop!”

The ‘midh’ overture is always accepted. It would be considered low not to accept it. Conflict was also resolved with ‘manazarah’ - when two parties would go to a neutral third party who negotiated peace between them.

J.N.: Let’s talk about Baloch women.

D.B.: A woman is held sacred. But in today’s world, this sacredness has become misshapen. In fear of being “tarnished” a woman becomes a prisoner in her home. In the end, these rules have become negative even though intentions were positive.

A woman is the primary force holding the family together, prodding men into ghairat when required, raising children with the right values.

A woman takes pride in embroidering her own dresses at home. The neatness and fineness of her designs is a reflection of her skill and earns her respect. At social functions, she enjoys showing off her handiwork.

Each embroidered design has a unique name. Before making the first stitch, she visualizes the composition of the whole piece: the colour of thread, floral designs and material. Time is then taken in selecting the right textured fabric for the piece at hand. Each piece reflects the hand that embroidered it.

Six basic colours are used in embroidered designs: yellow, blackish red, brown, blue, green, black. Other colours are optional. Needlework on piece usually begins with a zigzag line, a stripe which displays the six basic colours.

In Buleda, a special form of embroidery is undertaken on the back side of a material, and the pattern emerges on the face of the fabric. This type of embroidery is perfect both at the front and the back: no loose threads or knots. It’s hard to come by these pieces and they are pricey!

J.N.: What, to you, is most special about your land?

D.B.: Our fruits are sacred to us and we have respect for them. In Turbat, the date is prolific and we show respect for it by not throwing away its seed after eating the fruit. Instead, we discard it by putting it down gently. The city of Panjgur is known for its grapes: before harvest a sheep is slaughtered and its blood fed to the soil of the grape plants. This augurs a good harvest. Our apples and plums are luscious and of the finest quality. As you know, fruit from Balochistan sells well on any market.

J.N.: How is the pride in the cultural transmission kept intact?

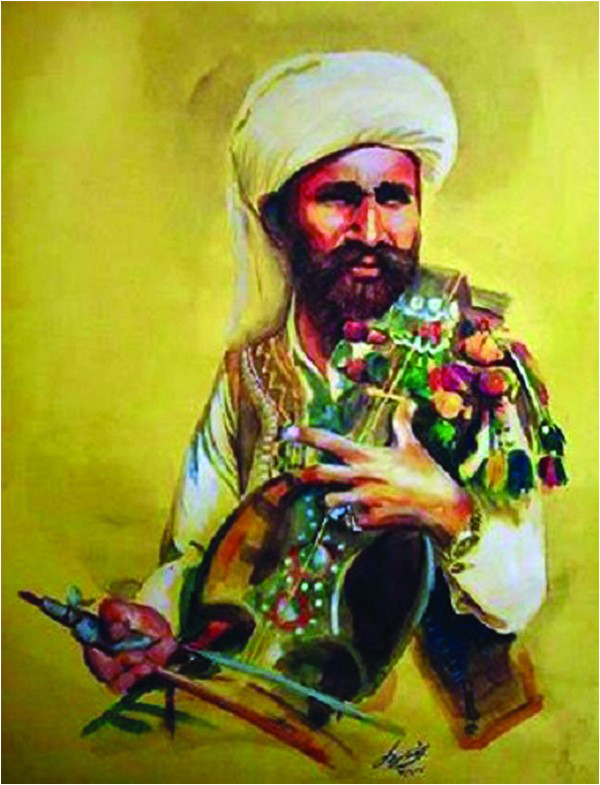

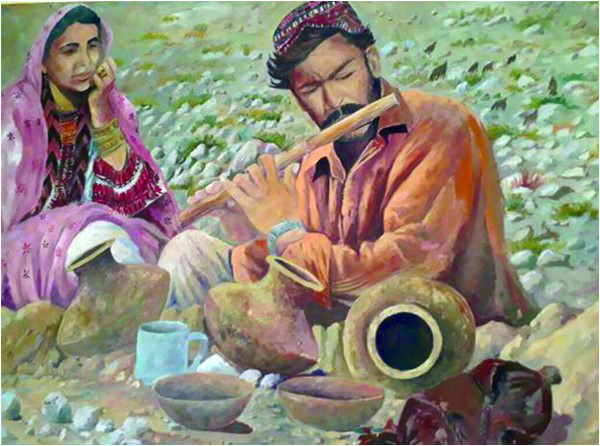

D.B.: Balochi poetry carries folk rituals to the next generation. A mother’s lullabies eulogize warriors and glorify tribal values - to acquaint their young with the land’s history.

Balochi poetry can be divided into public and private verses. A public verse starts with a couplet and as a couplet gets popular, people jump in to add new verses. Private verses are kept to a family.

The value of family relations is enjoined in this poem:

If thou live not in harmony with thy brother ,

Reasoning shall fail thee.

Thy abode shall fill with hot air.

Thy enemies will attack.

And inflict war on thee.

Thou art alone.

Thou cannot fight this war.

O live in harmony with thy brother

Love (ishqia) poems smite the heart with their delicacy.

Doshi man hayal e noken.

Disthun mardum e loduken.

Zeba heer pare mahthosen.

Mugaani wazir thausen

Laal man humsaran wath shaahan

Daab anth e hamo gumrahen

Sahth a zewaran zebame

Wath goen gabali mahear

“Last night I dreamt.

I saw a vision of grace.

Even the moon fainted as she came into view

O she is peacock among birds.

She, laughing with friends,

Walking with young grace,

Jewels sparkling with her laughter and movement

The moon smiling at her innocence.”

Baloch poetry is often topical; animal-related poems are part of the repertoire:

Donkey:

I slog under heavy loads.

Yet men demean and jeer

Bull:

Quiet, you spoiled boy,

From dawn to dusk it is I who labour in their fields.

Horse:

Men comb their hair and ride me,

Their grace they owe me.

On gory battlefields it is I who fights their wars.

Camel:

A rope ties bag upon bag on me.

Woman reclines for an easy ride.

Famine comes, I make do with weeds, thorns,

I carry on.

Cock:

Nights, they coop me in a shed,

It is my crow at first light that makes a new day for men.”

Jamile Naqi: We know so little of Balochistan. And we often hear only of troubles. What is the culture of Baloch people, in your view?

Danish Bashir: A certain view of “ghairat”, critical to Baloch identity, is a moral value that guides Baloch and they strive to live up to its code of conduct. Under the umbrella of ghairat are:

‘Insaan Dosti’ (friendship): Each person’s self (ego) is as important as the next person’s. No one must be put down. Similarly, we respect our own self and don’t allow it to be diminished. ‘Insaan Dosti’ is present in our dealings with each other (without our being aware of it.)

Our ‘zabaan’ (word) must be honoured.

Hospitality is central to us and even if our enemy seeks ‘panaa’ (shelter) with us, we are compelled by conscience to provide it.

We love our homeland. A Baloch who migrates is looked down upon and is called a ‘bhagora’ (runaway).

Honourable faithfulness, providing service and a helping hand - these are Baloch ideals. Atta Shad, a nationalist Balochi poet, expresses it as follows:

The price of the bowl of water in my land is enduring loyalty

Let’s quench our thirst and repay with ardent faithfulness

J.N.: What can you tell us about the famed Baloch fighting spirit?

D.B.: In geographical terms, Balochistan borders Iran, Afghanistan and Sindh. Baloch history is one of conflicts, wars and migrations. Migrations took place along the trade routes of Iran, Afghanistan and Sindh - and kings and warlords fought to crush the migrants. At times, Baloch had no option but to resort to being bandits and mercenaries in order to survive. The land is barren and people cannot live off it so easily.

Rugged mountainous terrain, harsh climate and conflicts led to a turbulent “no-frills” life. Personal disputes and friction between tribes could at times lead to feuds that went on for decades.

Balach Gorgej, an 18th century poet, pens the heroic, simple life and fighting spirit of the Baloch:

Gwat (Air)

“The mountains are the Baloch forts

Their companions the trackless cliffs

The lofty heights are (their) gwatg

Their water are the flowing springs

Their cups are made of dwarf-palm leaves

Their sitting places are thorny bushes

Their mattresses are bedsteads on the ground.

Their mounts are white leather sandals

Their sons are chosen arrows

their sons-in-law are pointed daggers

Their brothers are solid-rock spears

Their venerable (fathers) great-wounding scimitars”

J.N.: How and when did a cycle of revenge killings stop?

D.B.:There came a point when both sides were exhausted and a midh (peace) was undertaken: womenfolk take off their shawls and place them at the feet of their enemy’s patriarch, pleading,

“For God’s sake, we do not have enough menfolk left to fight. Let’s stop!”

The ‘midh’ overture is always accepted. It would be considered low not to accept it. Conflict was also resolved with ‘manazarah’ - when two parties would go to a neutral third party who negotiated peace between them.

J.N.: Let’s talk about Baloch women.

D.B.: A woman is held sacred. But in today’s world, this sacredness has become misshapen. In fear of being “tarnished” a woman becomes a prisoner in her home. In the end, these rules have become negative even though intentions were positive.

A woman is the primary force holding the family together, prodding men into ghairat when required, raising children with the right values.

A woman takes pride in embroidering her own dresses at home. The neatness and fineness of her designs is a reflection of her skill and earns her respect. At social functions, she enjoys showing off her handiwork.

Each embroidered design has a unique name. Before making the first stitch, she visualizes the composition of the whole piece: the colour of thread, floral designs and material. Time is then taken in selecting the right textured fabric for the piece at hand. Each piece reflects the hand that embroidered it.

Six basic colours are used in embroidered designs: yellow, blackish red, brown, blue, green, black. Other colours are optional. Needlework on piece usually begins with a zigzag line, a stripe which displays the six basic colours.

In Buleda, a special form of embroidery is undertaken on the back side of a material, and the pattern emerges on the face of the fabric. This type of embroidery is perfect both at the front and the back: no loose threads or knots. It’s hard to come by these pieces and they are pricey!

J.N.: What, to you, is most special about your land?

D.B.: Our fruits are sacred to us and we have respect for them. In Turbat, the date is prolific and we show respect for it by not throwing away its seed after eating the fruit. Instead, we discard it by putting it down gently. The city of Panjgur is known for its grapes: before harvest a sheep is slaughtered and its blood fed to the soil of the grape plants. This augurs a good harvest. Our apples and plums are luscious and of the finest quality. As you know, fruit from Balochistan sells well on any market.

J.N.: How is the pride in the cultural transmission kept intact?

D.B.: Balochi poetry carries folk rituals to the next generation. A mother’s lullabies eulogize warriors and glorify tribal values - to acquaint their young with the land’s history.

Balochi poetry can be divided into public and private verses. A public verse starts with a couplet and as a couplet gets popular, people jump in to add new verses. Private verses are kept to a family.

The value of family relations is enjoined in this poem:

If thou live not in harmony with thy brother ,

Reasoning shall fail thee.

Thy abode shall fill with hot air.

Thy enemies will attack.

And inflict war on thee.

Thou art alone.

Thou cannot fight this war.

O live in harmony with thy brother

Love (ishqia) poems smite the heart with their delicacy.

Doshi man hayal e noken.

Disthun mardum e loduken.

Zeba heer pare mahthosen.

Mugaani wazir thausen

Laal man humsaran wath shaahan

Daab anth e hamo gumrahen

Sahth a zewaran zebame

Wath goen gabali mahear

“Last night I dreamt.

I saw a vision of grace.

Even the moon fainted as she came into view

O she is peacock among birds.

She, laughing with friends,

Walking with young grace,

Jewels sparkling with her laughter and movement

The moon smiling at her innocence.”

Baloch poetry is often topical; animal-related poems are part of the repertoire:

Donkey:

I slog under heavy loads.

Yet men demean and jeer

Bull:

Quiet, you spoiled boy,

From dawn to dusk it is I who labour in their fields.

Horse:

Men comb their hair and ride me,

Their grace they owe me.

On gory battlefields it is I who fights their wars.

Camel:

A rope ties bag upon bag on me.

Woman reclines for an easy ride.

Famine comes, I make do with weeds, thorns,

I carry on.

Cock:

Nights, they coop me in a shed,

It is my crow at first light that makes a new day for men.”