China is one of the oldest living civilisations in the world, with an imperial period of two millennia. In the last few decades, its economy, military as well as the extent of its diplomacy have brought it front and centre in today’s international politics. However, this is not a straightforward consequence of political manoeuvring or technological advancement in contemporary times. China’s political orientation is profoundly shaped by its history and culture, particularly Confucianism.

As China’s power continues to rise, the need to explore how such an ancient culture manages to incorporate cultural norms of over 2,000 years into modern political governance becomes necessary, especially with regards to external and internal challenges.

Confucian values; the bedrock of Chinese society

Confucianism is a central aspect of Chinese culture and philosophy, since it advocates for a moral and political order in which hierarchy, respect for one’s superiors, equality and prioritisation of social over individual interests are key elements. Confucianism has governed how Chinese states and societies have operated for over 2,000 years, providing a template for social organisation that has persisted continents, seas and even revolutions.

Confucianism promotes a well-structured social hierarchy, with the expectation that leaders of society are morally upright individuals, otherwise the social order will be inevitably disrupted. “Benevolent governance” stands at the core of this doctrine: politically active classes are expected to devote themselves to constructive ends of public welfare, while the subjects reciprocate with allegiance and honour. The traditional respect for order and hierarchy, and for the authority of the Emperor, is still present today, albeit in a different political system: the Communist Party of China (CPC) often employs Confucian rhetoric to defend its rule and demonstrate its legitimacy. The notion of the CPC operating to preserve social harmony and the integrity of the nation very much comes from Confucianism.

Pragmatic evolution of the Communist Party

Nevertheless, the fact that the CPC embraces Confucianism does not rule out commitment to Marxism-Leninism; thus, this hybrid construction combines traditional ideas with the governance of the society built by socialism. From the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the policies of the CPC have been characterised by some degree of ideological stringency and a high degree of practical flexibility and even opportunism.

Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the party avoided Confucian values and resisted the temptations of embracing cultural lag, complying with the dictates of radical egalitarianism in its transformation. However, with the onset of the reformist era under Deng Xiaoping, Confucian ideals began to be reintegrated into state rhetoric.

In today’s political reality, this tradition has, under Xi’s leadership, become more pronounced. The cornerstone of Xi Jinping’s political philosophy, which is termed “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” does pride itself on understanding the very ancient concepts of China and modern socialist politics. He lauded the promotion of “core socialist values”, namely prosperity, democracy, and harmony, which of course, are often interpreted in harmony with the teachings of Confucius.

China has been insisting that the great sin was non-cooperation in common undertakings, even as alliances are formed and military power augmented to withstand the initiatives of the United States

In many respects, Xi’s Chinese Dream embodies the age-old desire of the Chinese people for national rejuvenation as well as social order and stability. In his policies, he focuses on the ideas of state integrity and strong power’s verticality and direct orientation towards ‘cultured China’ – much of which is expressed through Confucianism.

Under Xi’s leadership, it is no longer just culture upholding the Party, but rather, Confucianism becomes a means of sustaining the CPC’s power. Now the dominance of the Party is portrayed as the guarantee for protection of China’s culture and history.

Modern political practices: pragmatism and adaptation

Certainly, while political beliefs in China stem from the historical past, they have quite remarkably been able to adapt to modern practices. The post-Mao phase of China witnessed a radical shift from the strict communist economic policies to what Deng Xiaoping popularised as socialism with Chinese characteristics; a system that incorporated elements of market economy into the state-run economy constructed by the government. This practical outlook has greatly assisted in the transformation of China’s economy from that of an ‘underdeveloped country’ to a booming nation where it is ranked the second largest economy in the entire world.

For instance, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China is a contemporary political-economic strategy that portrays the intersection of Confucian values and contemporary pragmatism. Proponents of the Belt and Road Initiative portray it as a project aimed at enhancing global economic integration and encouraging economic growth through the strengthening connectivity between countries. Here, it is based on the congruence of Confucian ideals of harmony and mutual benefit. However, it is also designed to enable China to gain geopolitically, procure for its people, critics argue that it leads to debt dependency among some partner nations.

China's global diplomatic strategy: soft power meets hard power

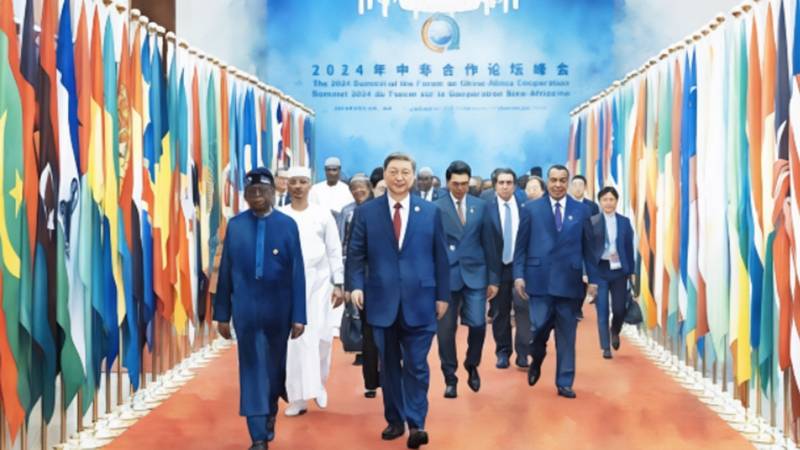

Evidently, global diplomacy has also taken into account the diverse factors of the culture and the socio-political environment. For instance, Tianxia (meaning “All under Heaven”) which refers to a great and benevolent leader ruling all the territories without any conflicts and wars can be found in the global order methods that China upholds. In this regard, China takes a firm position towards multilateral cooperation and actively positions itself as a protector of the United Nations and other multilateral mechanisms.

Arguably, these notions of civilising missions and the Confucian principles are only indicators of a much more bold policy that China pursues. The example of the South China Sea disputes illustrates this well. China is laying claim to most of the South China Sea, where it has built artificial islands complete with military installations. This policy has drawn ire and resistance from the regional countries and global organisations. While Beijing frames its modification of borders as asserting its sovereign claims, a number of observers have been critical of this manner of doing business as being contrary to the tenets of universal justice.

Finally, one also observes this combination of traditional and modern approaches to diplomacy in China’s interaction with the United States. Before Xi's leadership, relations with the US were cordial, but upon his ascendance, China has been in an aggressive mode, particularly regarding the US's policies of containment and the wars on trade.

Still, Beijing plays the role of a critic of a defeated unilateralism represented by the US. China has been insisting that the great sin was non-cooperation in common undertakings, even as alliances are formed and military power augmented to withstand the initiatives of the US.

A hybrid political identity

China’s political identity cannot be defined in entirely traditional or modern terms, because it has both the dimensions that coexist and compete – Confucianism and modern rule. The CPC has successfully placed itself as both the preserver of ancient Chinese traditions and the force who knows how to cope with modern global power dynamics. This is also important as China rises in the international community.

China’s success in this endeavour will be determined by the extent to which Chinese society is able to respond to the economic, technological and geopolitical changes of the 21st century.