In bygone days, early November mornings in Peshawar were crisp, the days chilly and the evenings nippy. The invigorating morning freshness was associated with the start of a new day, the changing season. The refreshing weather is now extinct, instead heralding a hazy smog season, in a city grappling with a population explosion, unregulated traffic, toxic gaseous emissions and particulate matter (PM2.5). Peshawar valley is surrounded by the historic Tatara (Khyber) and Momand mountain ranges, snow clad as the winters progressed. Locals warmed themselves in the traditional coal fired sandalis. Nowadays, the majestic mountain peaks during winters get shrouded in a dark haze of smog arising from the industrial estate and Jamrud areas bordering its western border.

Perched along an ancient caravan route, it was once called "Crossroads of Asia," where caravans from Turkestan, Persia, Arabia, Afghanistan, China, and India converged, historically as a gateway of Central Asia to South Asia. During the 1950s to 70s period, the famed “hippy trail” from Europe to Afghanistan, local and international tourists, double decker bus caravans, vintage automobiles and hitch hikers thronged the Peshawar streets, traditional serai-khanas and hotels on their way to India.

The scented air of jasmines and orange blossoms of the lush green boulevards of the cantonment and tranquil alleys and streets of the walled city are vanished, instead the noisy streets are now laden with a thick cloud of noxious air pollution, suffocating smoke and dust making breathing difficult, and a steady rise in hospital admissions with myriad respiratory and cardiac diseases, increased deaths especially of children and the elderly populations.

The childhood memories of Peshawar, renowned as a city of flowers and gardens by travellers and historians, evokes an aching nostalgia. As children and adults biked to their schools and workplaces on the tree lined Grand Trunk road, the clean walkways bustled with pedestrians and water carriers (bahistis) sprinkling water from their mashkizas.

This was before Pakistan became a willing partner to wage a Jihad against the erstwhile Soviet Union, when the entire region plunged into a never-ending conflict, terrorism became the buzzword and lost its standing as an attractive tourism hub for travellers. Once a city of narrow alleys and heritage sites, Kissa Khwani the famous storytellers’ bazaar, traders and artisans exhibiting their bronze, leather and porcelain wares; the evening whiffs of cannabis sifted through the packed street shops, serving charcoal roasted lamb, tikkas and chappal kebabs. The ambiance of kehwa-khanas serving cardamom scented green tea as travellers cushioned around the Persian carpets and straw mats made it a surreal experience. No wonder, travellers were attracted to the peaceful ambiance of the walled city.

Ironically, in the last four decades a “Dubai-style development” bug has overwhelmed the 2,000-year-old Peshawar’s cityscape, like other metropolises of South Asia. Mega projects, shopping malls and real estate high rises reflect the emergent ‘market’ economic reality. The progressive defacement, disfigurement and destruction of Peshawar is heartbreaking. The pervasive consumerism has divested heritage and old traditions, the past no longer figures in the “futuristic brick-and-mortar” model of development. Successive policy makers, administrators, planners and developers are callous about its peculiar history, architecture and heritage, transforming Peshawar into a faceless, soulless metropolis. The monstrous BRT is symbolic of this mindset, running massive concrete through heritage sites of the famed Grand Trunk Road, having demolished the vestiges of an inclusive city with bustling bazaars and interconnected communities.

The sense of belonging, feelings and memories for the few vestiges of the walled city of Peshawar have been subsumed by the ostentatious upwardly mobile, nouveau riche land grabbers, lacking in culture or refinement. This philistine culture has rapidly demolished iconic heritage sites (the Capitol Cinema and London Book being the recent victims in the cantonment) for ugly concrete commercial high rises. The successive Afghan wars and conflicts in the KP districts have compounded rural to urban demographic changes, when the traditional residents of walled city were forced out to shift to the new townships and the other metropolis of Pakistan. Hence the Peshawar of the bygone era exists in memory, save a few architectural jewels which will soon face the demolitions and concrete makeovers.

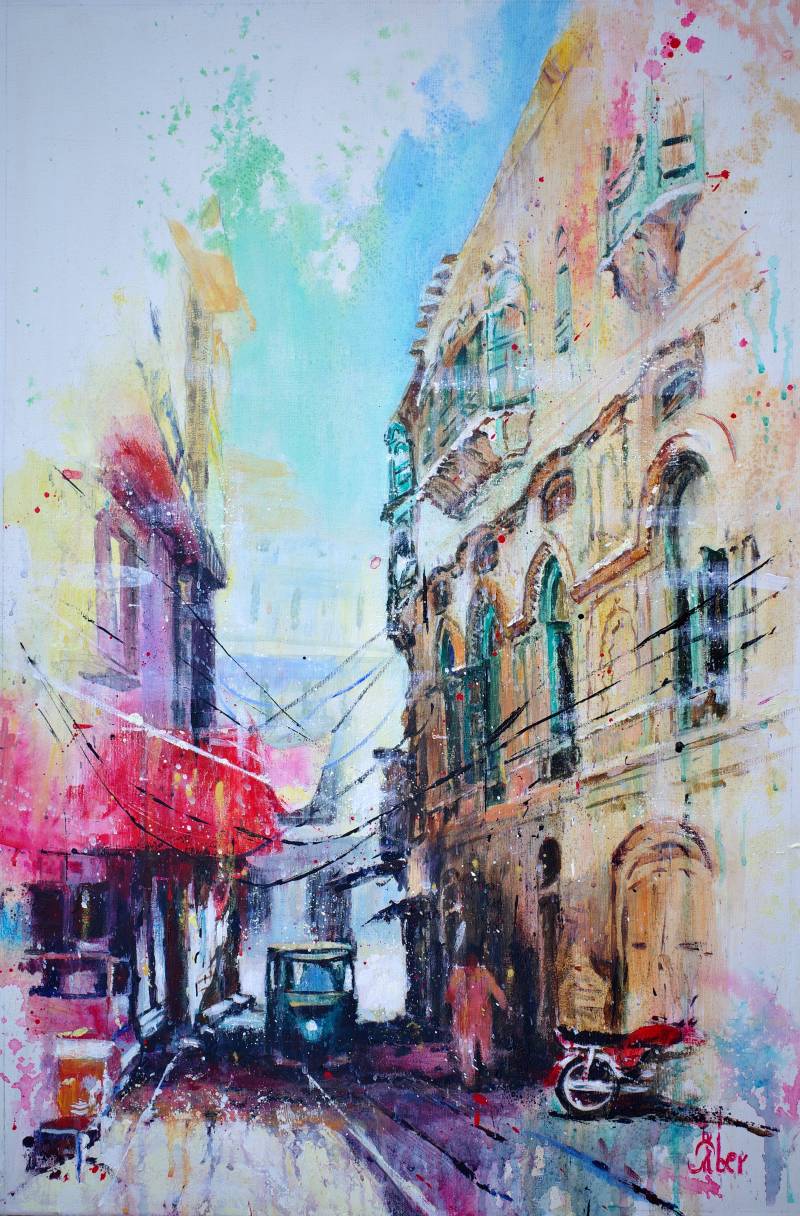

Like the Impressionists, Shabbir shows a vivid palette, glowing red and orange portray sunrises and sunsets, yellow sunlight beams, casting shadows with purple and violets

In November, Dr Ghulam Shabbir’s exhibition provided Peshawar a measure of nostalgia, coinciding with lecture by Prof Sayed Amjad Hussain from Toledo, Ohio in the USA, visiting Peshawar yearly for a series of visually colourful presentations, rejoicing the renowned personalities, vintage streets and sites of the Peshawar walled city. His latest presentation in the Albert and Victoria Hall Museum entitled: “Mery Bachpan ka Peshawar” mesmerised the audience.

Dr Shabbir’s art exhibition, “Marka e Ishq” (Conquest of the love for Peshawar), held at the historic Sethi House, served as reflection of the exquisite mohallahs, interconnected alleys and bazaars, minarets of the traditional walled city amid the hustle and bustle of an emerging amorphous Peshawar and its distasteful, slow asphyxiation of its heritage precincts. Having lived his early years inside the walled city, his master strokes echo the beauty of the exquisite architecture of the grand Sethi Mohalla, havelis of the Sethi families, the affluent traders of Peshawar city, trading wares from Russia, Central Asia, Caucuses and the subcontinent through caravans trade routes during 1880s until the early 20th century.

A self-taught painter who excels in water colours, Shabbir found his vocation as soon as he graduated from the prestigious Khyber Medical College in 1985, and later qualified as a professor of Pulmonology. The walled city of Peshawar and precincts of the Sethi Mohallah serves as an inspiration for the artist as France for the classic masters of the 19th century. Drawing inspiration from the impressionist painters, “his paintings are characterised by quick short master strokes, offering an unadorned impression of form, unblended colours with an emphasis on the depiction of natural light. The vibrant hues echo nostalgia and ecstasy as he revisits them through his paintings,” explains Tayyeba Aziz, a renowned Peshawar born water colourist.

Like the Impressionists, he “shows a vivid palette, glowing red and orange portray sunrises and sunsets, yellow sunlight beams, casting shadows with purple and violets. However, in the latest paintings the artiste emphasises shadows and less on colours, leaving lots of white areas as vignettes. His brush strokes are more bold which show the artist's commitment to keep searching for new techniques to further compliment his art form,” adds Tayyeba Aziz.

The exhibition explores the grandiose Sethi Mohallah precincts, about which researcher Samina Saleem in her doctoral thesis for Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) titled “Significant dilapidated havelis (residential places) in Peshawar, Pakistan” has summarised as follows:

“It seems that constructing massive residential places was a tradition of Peshawar city, because Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs who were financially well-off always liked to spend generously on their residential places. The woodwork in the buildings, which is very intricate especially doors and windows and the architectural style used in these Havelis, which is a combination of Hindu and Mughal building style and sometimes Central Asian influences can also be seen due to the strategic situation of Peshawar. Some havelis have fresco paintings representing a synthesis of old culture that prevailed in Peshawar.”