Dashing from pillar to post trying to squeeze in visits to relatives and friends alongside interviews of 2 feminist activist-artists for my unfolding book project on Queer Pakistani Performativities, and a third with the first Black Pakistani woman elected to parliamentary office for the major political party in the province of Sindh, the PPP or Pakistan People’s Party; chatting with my friend’s driver (who has been kindly transporting me hither n thither), about the economic meltdown that is making it almost impossible for the working classes to make ends meet; to being invited to dine in style at Karachi’s poshest restaurants and homes— all of this has reminded me yet again, how paradoxical and class-riven a place is Pakistan.

That paradox hit with full force when I was dining poolside at the stunning home of my friend Shamira’s tres elegante boss, a daughter in law of the famed late great singer Madame Noor Jehan. [Author’s Note: For a detailed discussion of Madame Noor Jahan’s famed career and unconventional lifestyle, see my book Siren Song: Understanding Pakistan Through its Women Singers. OUP, 2020]

While we were downing copious quantities of red wine in this Frenchwoman’s abode in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan —she has lived here on her own for 40+ years, even after divorcing her late husband, becoming a rich businesswoman on her own merit—as we dined on beef carpaccio salad followed by steak served medium rare with creamy potatoes au gratin deliciously crisped on top, a side of warm freshly baked French rolls, ending with a flourish of cheese and fruits and a most delectable strawberry tart with crust so delicate it crumbled the minute it touched our mouths—our hostess and her half French-half Swedish houseguest who is in the import/export business, informed us that a terrorist attack had occurred at the Superintendent Police’s office not far from where we sat. While my friend Shamira and I had been fully focused on our food, these two women had been simultaneously checking their newsfeed and started giving us a blow-by-blow account of what was unfolding: so many terrorists firing away, now so many injured, now all the terrorists killed and the injured taken to hospital, with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) taking responsibility for the attack. These extremists who had been supposedly disbanded or at least defanged by the Pak Army in the last decade, have suddenly reappeared as an alarming force in recent months, demanding a return to true Islam, coinciding with the installation once again of a Taliban govt next door in Afghanistan. Our host, worried about cancelled reservations at her restaurants in the aftermath of the attack, called up her manager and was reassured when he informed her that the reservation numbers were going up, not down. Such are the paradoxes of a country in the grip of revived terrorist violence in the midst of a terrible recession worsened by a debt default that the drivers I’ve spoken to in Karachi and Abu Dhabi (where I stopped for a day), say (as do most citizens) is a fault of corrupt elites filling their own pockets at the expense of the nation.

While we were downing copious quantities of red wine in this Frenchwoman’s abode in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan —she has lived here on her own for 40+ years, even after divorcing her late husband, becoming a rich businesswoman on her own merit—as we dined on beef carpaccio salad followed by steak served medium rare with creamy potatoes au gratin deliciously crisped on top, a side of warm freshly baked French rolls, ending with a flourish of cheese and fruits and a most delectable strawberry tart with crust so delicate it crumbled the minute it touched our mouths—our hostess and her half French-half Swedish houseguest who is in the import/export business, informed us that a terrorist attack had occurred at the Superintendent Police’s office not far from where we sat. While my friend Shamira and I had been fully focused on our food, these two women had been simultaneously checking their newsfeed and started giving us a blow-by-blow account of what was unfolding: so many terrorists firing away, now so many injured, now all the terrorists killed and the injured taken to hospital, with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) taking responsibility for the attack. These extremists who had been supposedly disbanded or at least defanged by the Pak Army in the last decade, have suddenly reappeared as an alarming force in recent months, demanding a return to true Islam, coinciding with the installation once again of a Taliban govt next door in Afghanistan. Our host, worried about cancelled reservations at her restaurants in the aftermath of the attack, called up her manager and was reassured when he informed her that the reservation numbers were going up, not down. Such are the paradoxes of a country in the grip of revived terrorist violence in the midst of a terrible recession worsened by a debt default that the drivers I’ve spoken to in Karachi and Abu Dhabi (where I stopped for a day), say (as do most citizens) is a fault of corrupt elites filling their own pockets at the expense of the nation.

My friend with whom I was staying has succeeded against all odds in challenging the patriarchal oppressions that defined her life by throwing off the shackles of abusive marriages twice over, and becoming a fabulous top chef running the kitchens that serve her mouthwatering menus at the best restaurants in Karachi, as well as the colonial era Sind Club. The latter may no longer have the sign “No women and dogs allowed” on its grand entrance red brick facade to greet visitors, but its patriarchal elitism is on display in every other way, including the fact that women cannot become members of the Club; their access has to be as wives, daughters, mothers or sisters of male members. Yet, my friend has succeeded in putting her stamp on this bastion of upper-class male privilege by training chefs and sous chefs to stand up for their rights, to demand better pay and herself refusing to play the victim role or batting her eye lashes at men to improve her social or economic status. She has remained resolutely single in a male dominated society after her two marriages dissolved as a consequence of emotional and physical abuse.

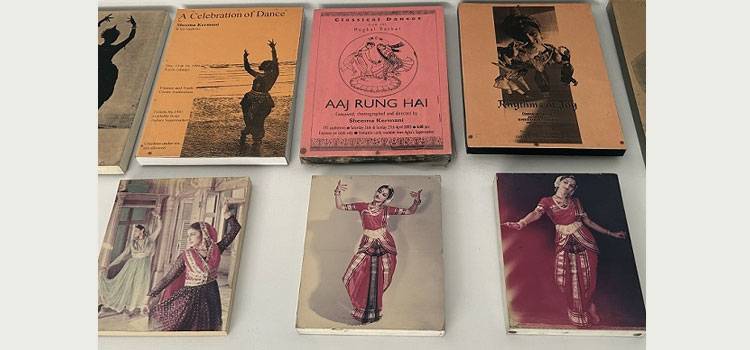

I had the privilege to meet several strong single women in all age groups who are defying norms and creating space for dissent through their artivism. One, a leading figure in Pakistan’s progressive and secular women’s movement, Sheema Kermani, who I’ve known for several decades and who started a dance and theatre group in Karachi in the 1980s called Tehrik I Niswan ( The Women’s Movement)—now heads up the globally recognised latest iteration of the secular women’s rights movement called Aurat March (the Women’s March, now in its 6th year)—which has broadened its umbrella to include transgender rights activists and has made an ever more concerted effort to expand the earlier Women’s Action Forum’s base to bring in working class urban as well as rural women and their issues into its fold. The main form this iteration of the movement takes is organising a rally in all major cities of Pakistan on International Women’s Day demanding rights especially bodily autonomy (mera jisam meri marzi!) as well as basic human rights including the right to employment, access to health care, freedom from sexual harassment, and transgender rights among others. Despite the opposing Haya March (organised by women belonging to the religious right-wing parties, primarily the Jamaat i Islami) as well as internal differences of opinion over strategy and direction within secular women’s rights groups and individuals, Aurat March has created an important transgressive space in the conservative body politic of the country.

I had the privilege to meet several strong single women in all age groups who are defying norms and creating space for dissent through their artivism. One, a leading figure in Pakistan’s progressive and secular women’s movement, Sheema Kermani, who I’ve known for several decades and who started a dance and theatre group in Karachi in the 1980s called Tehrik I Niswan ( The Women’s Movement)—now heads up the globally recognised latest iteration of the secular women’s rights movement called Aurat March (the Women’s March, now in its 6th year)—which has broadened its umbrella to include transgender rights activists and has made an ever more concerted effort to expand the earlier Women’s Action Forum’s base to bring in working class urban as well as rural women and their issues into its fold. The main form this iteration of the movement takes is organising a rally in all major cities of Pakistan on International Women’s Day demanding rights especially bodily autonomy (mera jisam meri marzi!) as well as basic human rights including the right to employment, access to health care, freedom from sexual harassment, and transgender rights among others. Despite the opposing Haya March (organised by women belonging to the religious right-wing parties, primarily the Jamaat i Islami) as well as internal differences of opinion over strategy and direction within secular women’s rights groups and individuals, Aurat March has created an important transgressive space in the conservative body politic of the country.

I also interviewed a young woman named Angeline Malik living on her own with her army of dogs, who is known for producing and directing bold plays and serials for satellite TV channels on topics considered taboo, such as lesbian relationships, contraception, a woman’s right of refusal, and so on. She refuses to cater to commercial demands for serials on same-old (misogynistic) themes of “pure” daughters-in-law vs. evil mothers-in-law, a favorite staple of TV dramas.

And I met and talked to women like my cousin Misbah Khalid who has carved out a niche for herself as an award winning top producer/director of plays, serials and telefilms, now working on a series of short plays examining various aspects and interpretations of Islamic law as it pertains to the rights of women in marriage, divorce, inheritance; her aim is to enlighten both herself and her audiences on rights many women don’t even realize are granted to them in Islam. She has also managed to raise two kids and keep her marriage in tact, no small feat in a country where many men are threatened by their wives careers especially in the entertainment industry which is still looked at with some suspicion through the lens of respectability politics.

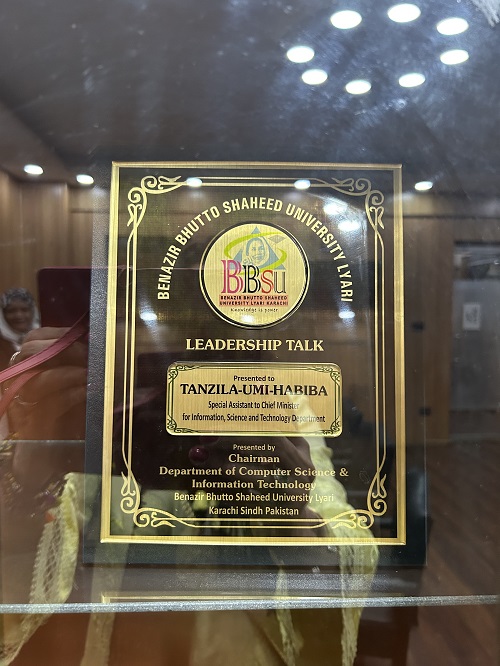

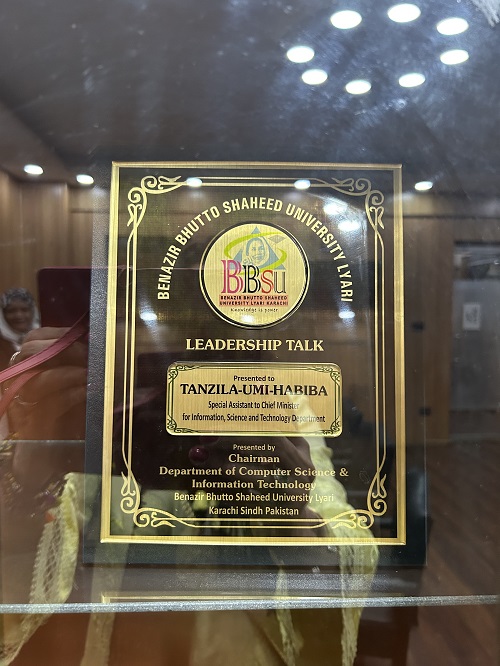

Tanzeela Qambrani, or Tanzeela Umme Habiba as she is commonly known (trans: Tanzeela, mother of Habiba)-is Pakistan’s first Black parliamentarian to be elected to office in the provincial assembly of Sind, on a major political party’s ticket- the People’s Party of Pakistan whose charismatic but deeply flawed leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became one of Pakistan’s most popular Prime Ministers during the 1970s. His daughter Benazir Bhutto followed in his footsteps a few decades later after he had been executed by the military dictator Zia Ul Haq. She too was assassinated in a terrorist attack and her abusive husband, who later became President. Both father and daughter thus, suffered a similar fate.

Tanzeela Qambrani, or Tanzeela Umme Habiba as she is commonly known (trans: Tanzeela, mother of Habiba)-is Pakistan’s first Black parliamentarian to be elected to office in the provincial assembly of Sind, on a major political party’s ticket- the People’s Party of Pakistan whose charismatic but deeply flawed leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became one of Pakistan’s most popular Prime Ministers during the 1970s. His daughter Benazir Bhutto followed in his footsteps a few decades later after he had been executed by the military dictator Zia Ul Haq. She too was assassinated in a terrorist attack and her abusive husband, who later became President. Both father and daughter thus, suffered a similar fate.

Tanzeela and I chatted about the many challenges she has had to face including being a member of one of the most marginalised communities in Pakistan, one that many don’t even know exists, the Sheedi community. These are people of African descent and part of its centuries-old diaspora eastwards, having settled along coastal areas of Sind in what is today Pakistan. Thanks to a colonial mindset inherited from British rule over two centuries, and a generalised racism that equates whiteness not only with beauty but also brains, Pakistani society has relegated Sheedis to what in India would be the lowest caste, the Untouchables or Dalits. Indeed, the first time I saw Tanzeela was on a zoom session during the pandemic, organized by the New York-based Equality Labs founded and run by Dalit feminists, in which she was participating in a conversation on the need for solidarity amongst disadvantaged communities across borders, with India’s Chandrasekhar Azad, chief of the Untouchables’ revolutionary organization, known as the Bhim Army. Cornel West was also a discussant and I came away from that virtual introduction to this amazing woman knowing I had to track her down and meet her whenever possible.

And so I did.

She graciously invited me to her office at the Ministry of Science and Information Technology, where I interviewed her about her life experiences and how she feels about being a Sheedi woman and the first representative of her community to the provincial assembly. She told me that despite all the difficulties and obstacles she has and continues to face due to her race, class and gender positionalities, and the current political and economic crises, she remains optimistic. “How can I not be hopeful about my country when its people have elected me and my party and it’s leadership accepts and is proud of me?” she quipped in response to a question I posed.

Her very presence on Pakistan’s political stage proves my point: the country’s citizenry is a resilient lot, two steps forward, one step back, several steps sideways.

Of such queer movement is paradox made. Eschewing labels, Pakistan befuddles and bewilders those who want to read it through normative lenses.

Next up: “From Islamabad to Lahore, with Love”

That paradox hit with full force when I was dining poolside at the stunning home of my friend Shamira’s tres elegante boss, a daughter in law of the famed late great singer Madame Noor Jehan. [Author’s Note: For a detailed discussion of Madame Noor Jahan’s famed career and unconventional lifestyle, see my book Siren Song: Understanding Pakistan Through its Women Singers. OUP, 2020]

While we were downing copious quantities of red wine in this Frenchwoman’s abode in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan —she has lived here on her own for 40+ years, even after divorcing her late husband, becoming a rich businesswoman on her own merit—as we dined on beef carpaccio salad followed by steak served medium rare with creamy potatoes au gratin deliciously crisped on top, a side of warm freshly baked French rolls, ending with a flourish of cheese and fruits and a most delectable strawberry tart with crust so delicate it crumbled the minute it touched our mouths—our hostess and her half French-half Swedish houseguest who is in the import/export business, informed us that a terrorist attack had occurred at the Superintendent Police’s office not far from where we sat. While my friend Shamira and I had been fully focused on our food, these two women had been simultaneously checking their newsfeed and started giving us a blow-by-blow account of what was unfolding: so many terrorists firing away, now so many injured, now all the terrorists killed and the injured taken to hospital, with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) taking responsibility for the attack. These extremists who had been supposedly disbanded or at least defanged by the Pak Army in the last decade, have suddenly reappeared as an alarming force in recent months, demanding a return to true Islam, coinciding with the installation once again of a Taliban govt next door in Afghanistan. Our host, worried about cancelled reservations at her restaurants in the aftermath of the attack, called up her manager and was reassured when he informed her that the reservation numbers were going up, not down. Such are the paradoxes of a country in the grip of revived terrorist violence in the midst of a terrible recession worsened by a debt default that the drivers I’ve spoken to in Karachi and Abu Dhabi (where I stopped for a day), say (as do most citizens) is a fault of corrupt elites filling their own pockets at the expense of the nation.

While we were downing copious quantities of red wine in this Frenchwoman’s abode in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan —she has lived here on her own for 40+ years, even after divorcing her late husband, becoming a rich businesswoman on her own merit—as we dined on beef carpaccio salad followed by steak served medium rare with creamy potatoes au gratin deliciously crisped on top, a side of warm freshly baked French rolls, ending with a flourish of cheese and fruits and a most delectable strawberry tart with crust so delicate it crumbled the minute it touched our mouths—our hostess and her half French-half Swedish houseguest who is in the import/export business, informed us that a terrorist attack had occurred at the Superintendent Police’s office not far from where we sat. While my friend Shamira and I had been fully focused on our food, these two women had been simultaneously checking their newsfeed and started giving us a blow-by-blow account of what was unfolding: so many terrorists firing away, now so many injured, now all the terrorists killed and the injured taken to hospital, with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) taking responsibility for the attack. These extremists who had been supposedly disbanded or at least defanged by the Pak Army in the last decade, have suddenly reappeared as an alarming force in recent months, demanding a return to true Islam, coinciding with the installation once again of a Taliban govt next door in Afghanistan. Our host, worried about cancelled reservations at her restaurants in the aftermath of the attack, called up her manager and was reassured when he informed her that the reservation numbers were going up, not down. Such are the paradoxes of a country in the grip of revived terrorist violence in the midst of a terrible recession worsened by a debt default that the drivers I’ve spoken to in Karachi and Abu Dhabi (where I stopped for a day), say (as do most citizens) is a fault of corrupt elites filling their own pockets at the expense of the nation.

My friend with whom I was staying has succeeded against all odds in challenging the patriarchal oppressions that defined her life by throwing off the shackles of abusive marriages twice over, and becoming a fabulous top chef running the kitchens that serve her mouthwatering menus at the best restaurants in Karachi, as well as the colonial era Sind Club. The latter may no longer have the sign “No women and dogs allowed” on its grand entrance red brick facade to greet visitors, but its patriarchal elitism is on display in every other way, including the fact that women cannot become members of the Club; their access has to be as wives, daughters, mothers or sisters of male members. Yet, my friend has succeeded in putting her stamp on this bastion of upper-class male privilege by training chefs and sous chefs to stand up for their rights, to demand better pay and herself refusing to play the victim role or batting her eye lashes at men to improve her social or economic status. She has remained resolutely single in a male dominated society after her two marriages dissolved as a consequence of emotional and physical abuse.

I had the privilege to meet several strong single women in all age groups who are defying norms and creating space for dissent through their artivism. One, a leading figure in Pakistan’s progressive and secular women’s movement, Sheema Kermani, who I’ve known for several decades and who started a dance and theatre group in Karachi in the 1980s called Tehrik I Niswan ( The Women’s Movement)—now heads up the globally recognised latest iteration of the secular women’s rights movement called Aurat March (the Women’s March, now in its 6th year)—which has broadened its umbrella to include transgender rights activists and has made an ever more concerted effort to expand the earlier Women’s Action Forum’s base to bring in working class urban as well as rural women and their issues into its fold. The main form this iteration of the movement takes is organising a rally in all major cities of Pakistan on International Women’s Day demanding rights especially bodily autonomy (mera jisam meri marzi!) as well as basic human rights including the right to employment, access to health care, freedom from sexual harassment, and transgender rights among others. Despite the opposing Haya March (organised by women belonging to the religious right-wing parties, primarily the Jamaat i Islami) as well as internal differences of opinion over strategy and direction within secular women’s rights groups and individuals, Aurat March has created an important transgressive space in the conservative body politic of the country.

I had the privilege to meet several strong single women in all age groups who are defying norms and creating space for dissent through their artivism. One, a leading figure in Pakistan’s progressive and secular women’s movement, Sheema Kermani, who I’ve known for several decades and who started a dance and theatre group in Karachi in the 1980s called Tehrik I Niswan ( The Women’s Movement)—now heads up the globally recognised latest iteration of the secular women’s rights movement called Aurat March (the Women’s March, now in its 6th year)—which has broadened its umbrella to include transgender rights activists and has made an ever more concerted effort to expand the earlier Women’s Action Forum’s base to bring in working class urban as well as rural women and their issues into its fold. The main form this iteration of the movement takes is organising a rally in all major cities of Pakistan on International Women’s Day demanding rights especially bodily autonomy (mera jisam meri marzi!) as well as basic human rights including the right to employment, access to health care, freedom from sexual harassment, and transgender rights among others. Despite the opposing Haya March (organised by women belonging to the religious right-wing parties, primarily the Jamaat i Islami) as well as internal differences of opinion over strategy and direction within secular women’s rights groups and individuals, Aurat March has created an important transgressive space in the conservative body politic of the country.

I also interviewed a young woman named Angeline Malik living on her own with her army of dogs, who is known for producing and directing bold plays and serials for satellite TV channels on topics considered taboo, such as lesbian relationships, contraception, a woman’s right of refusal, and so on. She refuses to cater to commercial demands for serials on same-old (misogynistic) themes of “pure” daughters-in-law vs. evil mothers-in-law, a favorite staple of TV dramas.

And I met and talked to women like my cousin Misbah Khalid who has carved out a niche for herself as an award winning top producer/director of plays, serials and telefilms, now working on a series of short plays examining various aspects and interpretations of Islamic law as it pertains to the rights of women in marriage, divorce, inheritance; her aim is to enlighten both herself and her audiences on rights many women don’t even realize are granted to them in Islam. She has also managed to raise two kids and keep her marriage in tact, no small feat in a country where many men are threatened by their wives careers especially in the entertainment industry which is still looked at with some suspicion through the lens of respectability politics.

Tanzeela Qambrani, or Tanzeela Umme Habiba as she is commonly known (trans: Tanzeela, mother of Habiba)-is Pakistan’s first Black parliamentarian to be elected to office in the provincial assembly of Sind, on a major political party’s ticket- the People’s Party of Pakistan whose charismatic but deeply flawed leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became one of Pakistan’s most popular Prime Ministers during the 1970s. His daughter Benazir Bhutto followed in his footsteps a few decades later after he had been executed by the military dictator Zia Ul Haq. She too was assassinated in a terrorist attack and her abusive husband, who later became President. Both father and daughter thus, suffered a similar fate.

Tanzeela Qambrani, or Tanzeela Umme Habiba as she is commonly known (trans: Tanzeela, mother of Habiba)-is Pakistan’s first Black parliamentarian to be elected to office in the provincial assembly of Sind, on a major political party’s ticket- the People’s Party of Pakistan whose charismatic but deeply flawed leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became one of Pakistan’s most popular Prime Ministers during the 1970s. His daughter Benazir Bhutto followed in his footsteps a few decades later after he had been executed by the military dictator Zia Ul Haq. She too was assassinated in a terrorist attack and her abusive husband, who later became President. Both father and daughter thus, suffered a similar fate.Tanzeela and I chatted about the many challenges she has had to face including being a member of one of the most marginalised communities in Pakistan, one that many don’t even know exists, the Sheedi community. These are people of African descent and part of its centuries-old diaspora eastwards, having settled along coastal areas of Sind in what is today Pakistan. Thanks to a colonial mindset inherited from British rule over two centuries, and a generalised racism that equates whiteness not only with beauty but also brains, Pakistani society has relegated Sheedis to what in India would be the lowest caste, the Untouchables or Dalits. Indeed, the first time I saw Tanzeela was on a zoom session during the pandemic, organized by the New York-based Equality Labs founded and run by Dalit feminists, in which she was participating in a conversation on the need for solidarity amongst disadvantaged communities across borders, with India’s Chandrasekhar Azad, chief of the Untouchables’ revolutionary organization, known as the Bhim Army. Cornel West was also a discussant and I came away from that virtual introduction to this amazing woman knowing I had to track her down and meet her whenever possible.

And so I did.

She graciously invited me to her office at the Ministry of Science and Information Technology, where I interviewed her about her life experiences and how she feels about being a Sheedi woman and the first representative of her community to the provincial assembly. She told me that despite all the difficulties and obstacles she has and continues to face due to her race, class and gender positionalities, and the current political and economic crises, she remains optimistic. “How can I not be hopeful about my country when its people have elected me and my party and it’s leadership accepts and is proud of me?” she quipped in response to a question I posed.

Her very presence on Pakistan’s political stage proves my point: the country’s citizenry is a resilient lot, two steps forward, one step back, several steps sideways.

Of such queer movement is paradox made. Eschewing labels, Pakistan befuddles and bewilders those who want to read it through normative lenses.

Next up: “From Islamabad to Lahore, with Love”