It was sometime in mid-1994 that Justice Saad Saood Jan invited me to his chamber in the newly constructed Supreme Court Building in Islamabad. I was working as a Supreme Court correspondent for a local newspaper. Justice Jan must have noticed my regular byline in the Peshawar based newspaper on reports related to Supreme Court proceedings.

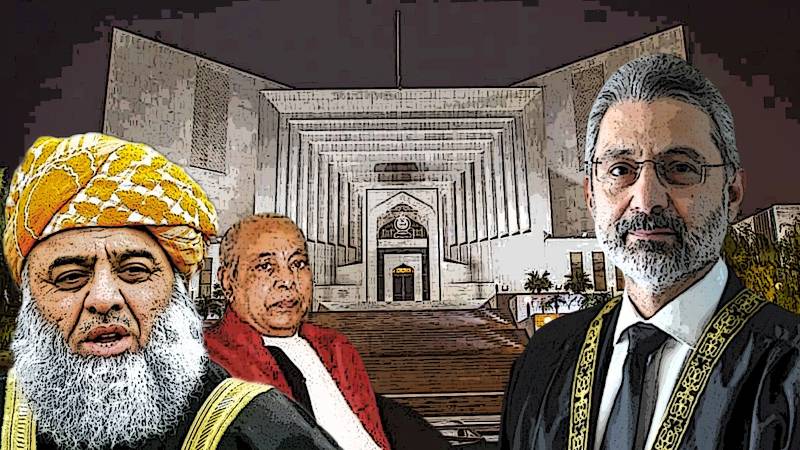

It was my second year as a reporter and I was obviously very excited to receive the invitation. But there was another reason for my excitement: it was a well-known fact in the judicial and legal circles of Islamabad that Benazir Bhutto wanted to appoint Justice Saad Saood Jan as the Chief Justice of Pakistan. He was the senior most judge, with a track record of moderate and liberal attitudes. Benazir Bhutto’s close ally, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, however was unhappy that someone whom he thought belonged to the Ahmedi community should be appointed Chief Justice. Maulana made his displeasure known through a poster campaign in Islamabad. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and other social media tools were decades away.

The walls of Zero Point market in Islamabad were full of posters in which Justice Saad Saood Jan was labelled as an Ahmedi, with slogans that his appointment as Chief Justice was completely unacceptable.

When I visited the Chamber of Justice Saad Saood Jan, he was perfectly composed but at the same time visibly disturbed, “I, judge of the Supreme Court, cannot advertise my faith. And if I am made to advertise my faith under pressure from some quarters, I will be displaying my bias in public… in such a situation, how can I adjudicate justice in cases where I have to decide points of law related to issues of faith among people of different religious sects and communities,” exclaimed Justice Jan in conversation with me that day.

It seems nothing has changed for our judiciary since the times of Justice Saad Saood Jan. It is the same cycle of intimidation, where the religious clergy forces judges to profess the intensity of their faith, and wear their religious orthodoxy on their sleeves.

There has been a visible decline in the quality and moral standards of judges in Pakistan’s superior judiciary. Justice Saad Saood Jan was an exceptional judge, even in his own time when the quality and moral standards of judges in the superior courts was not as low as it is in present times. I was stunned to watch the Chief Justice of Pakistan explaining articles of faith and details of orthodoxy - in court proceedings which were broadcast live - to a team of lawyers who were visibly flabbergasted. It seems nothing has changed for our judiciary since the times of Justice Saad Saood Jan. It is the same cycle of intimidation, where the religious clergy forces judges to profess the intensity of their faith, and wear their religious orthodoxy on their sleeves. I am forced by the toxic environment in present day Islamabad to make a comparison between Justice Jan’s situation and the situation Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa is facing.

Justice Isa has many advantages—he is living in times when people and the media are much more sensitized against using religion as a weapon in political and legal brawls. Paradoxically, the clergy is also well organized, more heavily funded and tech-savvy; they are deploying social media tools to shockingly intimidating results. So, Justice Isa understandably feels the pressure. What is not comprehensible is his response: he has utilized a fairly significant quantum of the court's precious time in explaining his position and delving into details of orthodoxy as they are understood by Islamist groups in our society. The higher moral standards Justice Jan displayed during his ordeal failed to act as a precedent for the incumbent Chief Justice of Pakistan.

Justice Jan set a venerable example in the 1990s. Although he came under immense pressure when Maulana Fazlur Rehman initiated a poster campaign against him, he refused to put his faith—or whatever he believed in - on public display. The question remains - how can a judge adjudicate on matters of justice when he becomes a party to a religious conflict and has to in turn, put on full display the orthodoxy he believes in?

Although traditional interpretations of Islam lay great emphasis on justice as a value in the society, our clergy seldom preaches justice. They instead advocate for dominance on the basis of political power and state authority that they claim to be exclusively theirs.

Justice, as a value, comes directly into conflict with political power and with state authority. Our religious clergy deals in political power and believes the Pakistani state to be part of its patrimony. They are guided by the belief that they have an inherent right to claim state authority—an authority which the clergy thinks it enjoys by way of the religious character of the state’s ideological foundations. Although our clergy does not enjoy any official position in the state structure, our clergy does not let any occasion or opportunity pass by wherein it has to assert its role as a dominant group in society on the question of religious faith, practice or anything related to whatever they consider orthodoxy.

Although traditional interpretations of Islam lay great emphasis on justice as a value in the society, our clergy seldom preaches justice. They instead advocate for dominance on the basis of political power and state authority that they claim to be exclusively theirs. In this environment of power oriented political and religious culture, where should an individual — helpless, powerless or excommunicated — look for help or justice?

At a more practical level, in what direction should the Pakistani citizen from the Ahmedi community, whose bail application was decided by Justice Isa look for justice? He is not powerful; he does not have orthodoxy on his side, and he is most certainly not claiming political power and state authority as part of his patrimony. Where should he go? He claimed under the provision of Pakistani law that he should be granted bail.

The clergy secured a place for themselves to dominate the political discourse when they forced political leadership to integrate religious orthodoxy into our constitutional framework. The arguments our clergy is deploying against the Chief Justice originate from the vestiges of the debate on religious orthodoxy that took place in our parliament back in September 1974.

If we are to listen to what Maulana Fazlur Rehman has to say, this individual from the Ahmed community does not have a right to be granted a hearing. And consequently, the Chief Justice of Pakistan does not have the right to pass a verdict on his bail application. Not only that, the Chief Justice has been forced to reiterate the articles of faith in an open court as desired by the clergy. The clergy says these articles of faith or orthodoxy prevent the judiciary from taking up such matters for adjudication.

As a society, we hardly make any attempt to explore even our own history – both history which is recent, which is taking shape in the status quo and a history in whose aftermath we are presently living our lives. The clergy secured a place for themselves to dominate the political discourse when they forced political leadership to integrate religious orthodoxy into our constitutional framework. The arguments our clergy is deploying against the Chief Justice originate from the vestiges of the debate on religious orthodoxy that took place in our parliament back in September 1974.

What the Pakistani parliament did on September 7, 1974, hardly has any precedence in Islamic history. Orthodoxy has largely been a Christian concept, consisting of a centralizing church authority. The concept, according to scholars, has largely been alien to Islam. Yet this move in 1974 came out as a result of the alliance of the religious clergy and political leadership, to designate what, they thought, were “acceptable beliefs” in the Islamic context. The orthodoxy constructed and inserted into the legal system by the legislative branch of the state in 1974 borrowed heavily from the victim community’s theological techniques.

A person should be treated as a citizen, not as a member of any particular religious sect, community or grouping. Whoever is a citizen of Pakistan should have equal legal rights and status within the framework of the Pakistani Constitution.

In the more than 400 pages of the record of cross examination of the leader of the Ahmedi community, Mirza Nasir, Pakistan’s Attorney General used the Ahmedi community’s concept of excommunication of majority Muslims from the folds of Islam to bring home the point that the victim community could as well be pushed out of the ambit of Islam on theological ground in the same manner. During cross examination, the Attorney General Yahya Bakhtiar repeatedly asked the leader of the Ahmedi community his opinion about the theological concept of takfir, and in the process, attempted to justify the legislature pronouncing takfir against the Ahmedi community. The passage of the 2nd Amendment was a clear indication that the modernist class which dominated the political system of the country was conceding ground to the religious clergy. The Bhutto regime was forced to shift from a quasi-secular outlook to a position where it had to sponsor an amendment in the Constitution that created a new division, based on religious beliefs in society.

Irrespective of what the role of religious orthodoxy is in traditional interpretations of Islam, or what argument modernist Islam could deploy against the use of the orthodoxy to influence judicial processes in the country, we are presently confronted with a moment in our history where the clergy can simply do away with whatever semblance of political modernity is left in the functioning of our state and society.

A person should be treated as a citizen, not as a member of any particular religious sect, community or grouping. Whoever is a citizen of Pakistan should have equal legal rights and status within the framework of the Pakistani Constitution. No religious group or individual should be discriminated against. The judiciary should be independent, free and impartial. These are the minimum requirements of political and legal modernity. The path towards which the religious clergy is pushing us and the path which has been forced upon the Chief Justice of Pakistan leads straight towards anarchy.

The incumbent Chief Justice of Pakistan would do well to consult the notes of Justice Saad Saood Jan if they exist in the records of the Supreme Court’s archives.