Faheem Farooqi, also known as Faheem ‘Commando’, is still remembered as one of MQM’s notorious militants in the 1990s, a man who topped the security agencies’ most-wanted lists. He was arrested in August 1995, two months prior to an attack on the Sindh secretariat building in Karachi. General Naseerullah Babar, a man known for his zero tolerance policies, and who was leading the then operation in Karachi against the MQM, was aggrieved by the fact that Commando was being kept alive in police custody. The day after the attack on the provincial secretariat, Commando was killed in a so-called ‘police encounter’. He was handcuffed at the time of his death. Close to the time of Commando’s arrest, another MQM militant, Farooq Patni, also known as Farooq ‘Dada’, was similarly killed in a police encounter. According to an official serving in Karachi at the time, both Dada and Commando were in police custody when they died.

The officer involved in both these police killings has of late been the subject of much discussion in Pakistan. Rao Anwar was the product of the securitisation policies of the 1990s. The General Babar’s operation allowed him, and his fellow officials, to eliminate the likes of Dada and Commando. He then scaled the ranks because of the patronage he received from both political and military elites. Over time, his team became all-powerful, almost untouchable, with limited oversight from his superiors. On their part, the PSP cadre ignored, shrugged off, or remained silent about such practices. Those officers who refused to condone extrajudicial killings, were transferred to Islamabad.

Since the 1990s, if not earlier, the governments of the PPP and PML-N came into power with pledges of eradicating police violence, an abuse of which they themselves had been victims, only to allow police militarisation to blossom for their own political gains, resulting in the continuation of police encounter killings. One of the grounds for the PPP’s dismissal in 1996 was extrajudicial killings by the police in Karachi. Successive regimes continued to patronise different police officials for the purposes of either suppressing political opposition or enabling their own economic growth in select neighbourhoods. Others were transferred and posted selectively for the sake of increasing the number of votes dropped in ballot boxes for nominated candidates.

A few years back, Karachi had another superintendent of police who had similarly climbed the ranks and operated with an independence that breached the threshold of discretion normally afforded to police officials. In July 2006, the late SP Chaudhry Aslam was leading the Lyari Task Force. The LTF detained a man named Rasool Bux Brohi. He was later killed in Gadap, District Malir. The LTF was charged with the murder of Brohi—a peasant, whom the LTF tried to pass off as Mashooq Brohi—a notorious dacoit. The case gained notoriety and a police investigation revealed that the encounter had, in fact, been fake. Criminal proceedings took place and police officials of the LTF, including Aslam, were suspended and arrested. And just as we are seeing with the family and friends of Naqeebullah Mehsud, but on a lesser scale, those close to Rasool Bux had provided detailed accounts of how he was picked up by the police prior to his death.

Journalists and senior police officials acknowledge in private how corrupt, both morally and financially, was Chaudhry Aslam. Yet upon his death he was mourned and celebrated. He was commended for his extra-legal ways, his vigilante justice, his fearless attitude. He was remembered as the ‘encounter cop’, the ‘top cop’, and referred to as a dabangg police officer. An international newspaper referred to him as ‘Pakistan’s toughest cop’. In essence, our media and society made a hero out of a Dirty Harry. Collectively, we legitimised Aslam’s potentially illegal practices. And they continued through the services of other policemen who idolised Aslam, and would later eulogise Anwar, and who similarly strived to improve their financial standing in the city as well as their professional profiles. Then there were those who believed that acting above the law was the only way to restore it.

The media has frequently reported on the number of ‘terrorists’ killed in police encounters with little-to-no investigation into who the victims of these encounters were. Reporters covering the aftermath of said encounters will routinely tell you off-the-record how the encounter was staged and that the “agencies had provided the police” with either the whereabouts of the suspects or the suspects themselves. But this is information which cannot be published and broadcast, both for lack of empirical evidence as well as due to fear of the repercussions following such disclosures.

Over time, encounters have become a numbers game. Certain police officials even inflate the number of people they have killed in both staged and genuine encounters for promotions and recognition. “The first one is always a little difficult to digest,” one police inspector told me. “I could not sleep after that killing for some time. But then you get used to it.” This desensitization is made easier when the prospects of upward mobility are contingent upon who you have eliminated and which group they belonged to. In these pages, Mahim Maher has referred to how encounters raise the ‘rishwat rates’, or the financial demands made by police officials for releasing suspects in custody, which is part of Karachi’s police economy. This also includes active participation in land grabbing, running drug dens, and benefitting from the informal economy more generally in attempts to compensate for their otherwise meagre salaries.

Fake or staged encounter killings by the police are thus symptoms of a complicated culture of policing and they cannot be reduced to Aslams or Anwars. Pakistan’s police culture has produced and is likely to continue producing police officers who prefer zero-tolerance policies, who belong to a society that advocates vigilante justice and in the upper echelons of which men and women alike react to the deaths of criminals and suspected terrorists by exclaiming, ‘Acha hua maar diya’ (Good he was killed). We are all guilty of romanticising encounter cops, believing them to be essential for our national and individual security, and failing to condemn state policies that have directly or indirectly allowed these practices to persist for almost three decades. Perhaps the tragic killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud will reverse these trends.

Zoha Waseem is a PhD candidate at King’s College London. @ZohaWaseem.

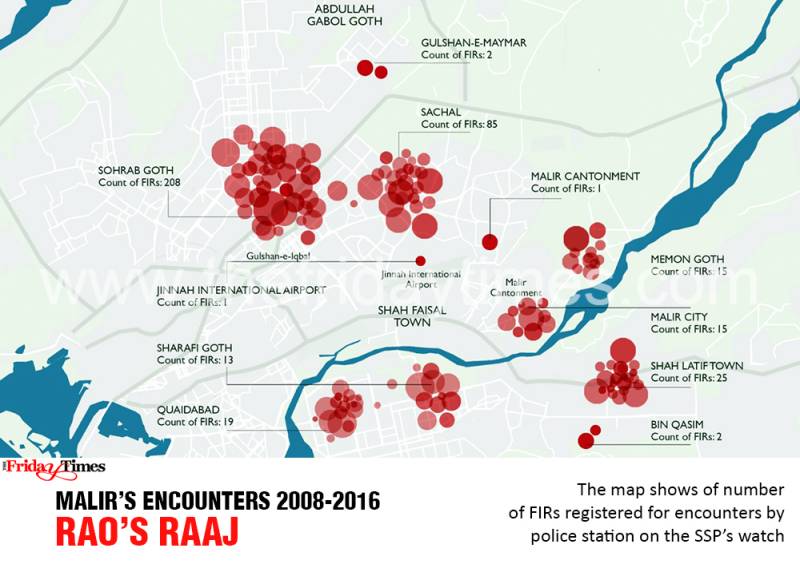

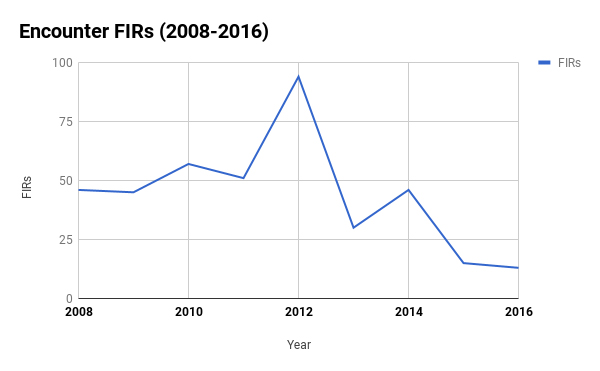

Data scraped by Shahzeb Ahmed, a digital journalism lecturer at the IBA's Centre for Excellence in Journalism in Karachi.

Mapping by Armeen Tinwalla.

The officer involved in both these police killings has of late been the subject of much discussion in Pakistan. Rao Anwar was the product of the securitisation policies of the 1990s. The General Babar’s operation allowed him, and his fellow officials, to eliminate the likes of Dada and Commando. He then scaled the ranks because of the patronage he received from both political and military elites. Over time, his team became all-powerful, almost untouchable, with limited oversight from his superiors. On their part, the PSP cadre ignored, shrugged off, or remained silent about such practices. Those officers who refused to condone extrajudicial killings, were transferred to Islamabad.

Our media and society made a hero out of a Dirty Harry. Collectively, we legitimised the late Chaudhry Aslam's potentially illegal practices

Since the 1990s, if not earlier, the governments of the PPP and PML-N came into power with pledges of eradicating police violence, an abuse of which they themselves had been victims, only to allow police militarisation to blossom for their own political gains, resulting in the continuation of police encounter killings. One of the grounds for the PPP’s dismissal in 1996 was extrajudicial killings by the police in Karachi. Successive regimes continued to patronise different police officials for the purposes of either suppressing political opposition or enabling their own economic growth in select neighbourhoods. Others were transferred and posted selectively for the sake of increasing the number of votes dropped in ballot boxes for nominated candidates.

A few years back, Karachi had another superintendent of police who had similarly climbed the ranks and operated with an independence that breached the threshold of discretion normally afforded to police officials. In July 2006, the late SP Chaudhry Aslam was leading the Lyari Task Force. The LTF detained a man named Rasool Bux Brohi. He was later killed in Gadap, District Malir. The LTF was charged with the murder of Brohi—a peasant, whom the LTF tried to pass off as Mashooq Brohi—a notorious dacoit. The case gained notoriety and a police investigation revealed that the encounter had, in fact, been fake. Criminal proceedings took place and police officials of the LTF, including Aslam, were suspended and arrested. And just as we are seeing with the family and friends of Naqeebullah Mehsud, but on a lesser scale, those close to Rasool Bux had provided detailed accounts of how he was picked up by the police prior to his death.

Journalists and senior police officials acknowledge in private how corrupt, both morally and financially, was Chaudhry Aslam. Yet upon his death he was mourned and celebrated. He was commended for his extra-legal ways, his vigilante justice, his fearless attitude. He was remembered as the ‘encounter cop’, the ‘top cop’, and referred to as a dabangg police officer. An international newspaper referred to him as ‘Pakistan’s toughest cop’. In essence, our media and society made a hero out of a Dirty Harry. Collectively, we legitimised Aslam’s potentially illegal practices. And they continued through the services of other policemen who idolised Aslam, and would later eulogise Anwar, and who similarly strived to improve their financial standing in the city as well as their professional profiles. Then there were those who believed that acting above the law was the only way to restore it.

Police officers who prefer zero-tolerance policies belong to a society that advocates vigilante justice. In its upper echelons men and women react to the deaths of criminals and suspected terrorists by exclaiming, 'Acha hua maar diya' (Good he was killed)

The media has frequently reported on the number of ‘terrorists’ killed in police encounters with little-to-no investigation into who the victims of these encounters were. Reporters covering the aftermath of said encounters will routinely tell you off-the-record how the encounter was staged and that the “agencies had provided the police” with either the whereabouts of the suspects or the suspects themselves. But this is information which cannot be published and broadcast, both for lack of empirical evidence as well as due to fear of the repercussions following such disclosures.

Over time, encounters have become a numbers game. Certain police officials even inflate the number of people they have killed in both staged and genuine encounters for promotions and recognition. “The first one is always a little difficult to digest,” one police inspector told me. “I could not sleep after that killing for some time. But then you get used to it.” This desensitization is made easier when the prospects of upward mobility are contingent upon who you have eliminated and which group they belonged to. In these pages, Mahim Maher has referred to how encounters raise the ‘rishwat rates’, or the financial demands made by police officials for releasing suspects in custody, which is part of Karachi’s police economy. This also includes active participation in land grabbing, running drug dens, and benefitting from the informal economy more generally in attempts to compensate for their otherwise meagre salaries.

Fake or staged encounter killings by the police are thus symptoms of a complicated culture of policing and they cannot be reduced to Aslams or Anwars. Pakistan’s police culture has produced and is likely to continue producing police officers who prefer zero-tolerance policies, who belong to a society that advocates vigilante justice and in the upper echelons of which men and women alike react to the deaths of criminals and suspected terrorists by exclaiming, ‘Acha hua maar diya’ (Good he was killed). We are all guilty of romanticising encounter cops, believing them to be essential for our national and individual security, and failing to condemn state policies that have directly or indirectly allowed these practices to persist for almost three decades. Perhaps the tragic killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud will reverse these trends.

Zoha Waseem is a PhD candidate at King’s College London. @ZohaWaseem.

Data scraped by Shahzeb Ahmed, a digital journalism lecturer at the IBA's Centre for Excellence in Journalism in Karachi.

Mapping by Armeen Tinwalla.