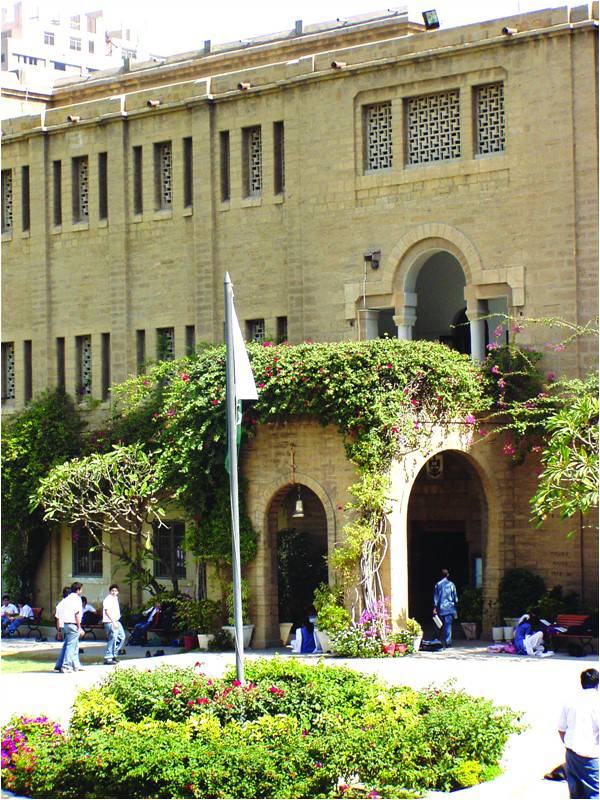

When it comes to egos, size matters. The sumptuous red-brick monuments sprawling across acres of lavish greens, in the heart of the city, are schools that dwarf the most opulent of homes. Armed sentinels at the gates salute the school owners, like soldiers saluting Generals. Next their chauffeur-driven Mercedes and BMWs sail down the winding driveways to deposit them in front of their plush offices.

It is true that exorbitant fees have helped turn education into a business like any other. Parents, especially those owning successful businesses, understand the power of profit over the pedestrian delivery of products and services. For them, education is just another service: the more one sells the more one makes. But while self-regulating market forces cap prices for most goods, education requires regulation to do it. Now that this has been done, the laws must be respected. Otherwise, say parents, broken laws can only be repaired and restored by the judges in court.

The recent legal victory of parents of English medium private schools against private school-owners breaking the fee-cap rules, is indicative of a rising tension between the two groups. (In 2015, parents in Islamabad were outraged when fees suddenly went up. The Private Educational Institutions Regulatory Authority tried to regulate fees by 2016 but private schools took them to court repeatedly and the Islamabad High Court ruled in their favour. These verdicts were challenged. But at one point, the Supreme Court had to tell the Islamabad High Court to take a decision as private schools were doing what they wanted as the case dragged on. In Sindh, the court restrained private schools from raising their fee by more than 5% until it decided petitions in 2017.) Parents want schools to follow the laws, not bend or break them as they please. Period.

Schools have a longer list of gripes: the rising tide of inflation, higher maintenance costs such as those for structural upgrades, repairs and construction. All delays (mostly for reasons beyond owner control) in any school-admin activity costs much more than budgeted for. Competition provokes salary raises due to teacher turnover, enrolments and dropouts.

But what has the friction between them to do with education, what is taught and why and how it is taught? What does it have to do with how much children actually learn in order to become well-informed, discerning citizens with a broad range of skills that enable problem-solving?

Nothing, really. Or very very little. Our imposing bricks-and-mortar education factories, with their state-of-the-art facades, still run on outdated textbooks (quality and content), minimal courseware and little or no teacher training. Technology-enabled education content remains peripheral and teacher content knowledge evaporates into nothingness when tested. And yet, despite all this, student performance is optimal in the final year of O’ and A’ level exams. Students graduate with a startling array of As, enough to unlock the ivory portals of world-renowned colleges.

How is this possible? In a whisper, the answer is twofold: “private tutoring and home-teaching”.

Without intending to, private schools end up behaving like farms that tutors comb to lure underperforming students into their tutoring parlours. Most students fail in class because their schools fail. Most are bright but distracted and confused by what teachers teach and how they teach it. By contrast, during their tutoring phase—which could last anything from six months to four years—students gain a better understanding of what they are taught in class, practise what they understand, and finally do mock tests to display their recall of all they practised. This vigorous cycle is repeated for as long as is needed to produce expensive turbo boosts in exam grades.

Many highly educated parents, however, trust their own credentials and experience more than the tutors’, to demonstrate essential topic-concepts to their children. They explain the underlying rationale and help the child make logical connections so often missing in school texts, or in the teacher’s instructions. Some parents perform like exceptional guru-teachers: they ensure that the child enjoys understanding truly and deeply the topic being taught. Such parents (often moms for elementary school), devote their entire evenings (specially during exam season) five days a week, tutoring their children.

Today it has become a norm to see our schools operate like (a) homework-manufacturing agencies and (b) testing and examination centres. During the interval between (a) and (b), much of the teaching-learning activities are conveniently outsourced to parents and private tutors.

The obvious question then is: what purpose are elite English medium schools serving if they can’t offer exam success or quality education?

Most elite Pakistani English medium schools appear to serve a higher purpose, one regarded as being far superior to education i.e. social networking. For pupils from age six and upwards, elite schools and their user-base ensure that the who’s who of Pakistan maintain their privileged status for generations. Fashionable school brands offer them the playground, halls, stage, and subsequently homes to intermingle and incubate long-term friendships. These will pay off one day as adult “connections” that allow fluid entry into lucrative high-end jobs, portals for marriages and keys to businesses. The accepted bottomline is: It’s social connections, not education, that counts.

While schools pocket fees together with undeserved credit for their students’ exceptional academic performance, parents dismiss their own tireless efforts nonchalantly with a shrug that seems to convey, what can’t be cured must be endured. Tutors, on the other hand, are content to be self-effacing as long as business is good. For them, the goal of education is to help students obtain spectacular grades in exams. In return, grateful schools deliver to them an unending stream of under-achievers every year.

The invaluable inputs from parents and critical interventions by tutors, so conveniently underemphasised, flow quietly like electricity, to power school-branding. Successful school brands grow on the back of the efforts of hard-working parents and tutors. But schools flash them like incandescent halos swimming above the heads of “their brilliant students”. It is ironic that parents rally around the halo because their personal stake in creating it lends a much-needed privilege status to their children’s school. Throughout the 12 long years of their school life, kids get to “go where it matters”.

It would be unfair to accuse schools, parents and tutors of any conscious complicity in setting up a seamless ecosystem generating a three-way conduit for distributing mutual benefits. An ecosystem does not thrive on complicity. It grows systemically and organically because of the intrinsic nature of the forces connecting them. Raising the value of “connections” over and above education, draws upon past experience. And most experiences flow out of values and beliefs in practice.

It is distressing that parents protest the upward spiral of school fees without demanding better education to show for it. If our children received the quality education they deserved exclusively from upscale schools, parents’ savings in supplementary tutoring would be substantial.

If schools promised quality education by asking for a small share of such savings, to invest in better courseware, teacher training, technology and greater, faster in-depth learning, parents would see their children enjoy exceptionally high levels of academic success. More importantly, exam success, and by corollary opportunities for future livelihoods, would no more be the exclusive preserve of those who can afford private tuition. It would extend to a much broader base of the student population, generating fierce completion and a genuine striving for academic excellence.

The cherry on the cake would be a refreshing new insight: that true and meaningful education, even without earning top grades, is preferable to one that is meaninglessly regurgitative but ornamented with star-studded grades.

Connecting the increase in school fees to the delivery of quality education makes more sense than schools charging more fees because they can. Or parents taking them to court for it simply because they can.

The writer is an Ed.M (Harvard), a member of the National Association of Mathematics Advisors UK and has also worked in Canada. He introduced Dyslexia and Math Learning Disabilities in Pakistan (1986) and set up the first Remedial Centre in Karachi (1987) (R.E.A.D.) @ShadMoarif

It is true that exorbitant fees have helped turn education into a business like any other. Parents, especially those owning successful businesses, understand the power of profit over the pedestrian delivery of products and services. For them, education is just another service: the more one sells the more one makes. But while self-regulating market forces cap prices for most goods, education requires regulation to do it. Now that this has been done, the laws must be respected. Otherwise, say parents, broken laws can only be repaired and restored by the judges in court.

Parents protest the upward spiral of school fees without demanding better education to show for it

The recent legal victory of parents of English medium private schools against private school-owners breaking the fee-cap rules, is indicative of a rising tension between the two groups. (In 2015, parents in Islamabad were outraged when fees suddenly went up. The Private Educational Institutions Regulatory Authority tried to regulate fees by 2016 but private schools took them to court repeatedly and the Islamabad High Court ruled in their favour. These verdicts were challenged. But at one point, the Supreme Court had to tell the Islamabad High Court to take a decision as private schools were doing what they wanted as the case dragged on. In Sindh, the court restrained private schools from raising their fee by more than 5% until it decided petitions in 2017.) Parents want schools to follow the laws, not bend or break them as they please. Period.

Schools have a longer list of gripes: the rising tide of inflation, higher maintenance costs such as those for structural upgrades, repairs and construction. All delays (mostly for reasons beyond owner control) in any school-admin activity costs much more than budgeted for. Competition provokes salary raises due to teacher turnover, enrolments and dropouts.

But what has the friction between them to do with education, what is taught and why and how it is taught? What does it have to do with how much children actually learn in order to become well-informed, discerning citizens with a broad range of skills that enable problem-solving?

Nothing, really. Or very very little. Our imposing bricks-and-mortar education factories, with their state-of-the-art facades, still run on outdated textbooks (quality and content), minimal courseware and little or no teacher training. Technology-enabled education content remains peripheral and teacher content knowledge evaporates into nothingness when tested. And yet, despite all this, student performance is optimal in the final year of O’ and A’ level exams. Students graduate with a startling array of As, enough to unlock the ivory portals of world-renowned colleges.

How is this possible? In a whisper, the answer is twofold: “private tutoring and home-teaching”.

Without intending to, private schools end up behaving like farms that tutors comb to lure underperforming students into their tutoring parlours. Most students fail in class because their schools fail. Most are bright but distracted and confused by what teachers teach and how they teach it. By contrast, during their tutoring phase—which could last anything from six months to four years—students gain a better understanding of what they are taught in class, practise what they understand, and finally do mock tests to display their recall of all they practised. This vigorous cycle is repeated for as long as is needed to produce expensive turbo boosts in exam grades.

The invaluable inputs from parents and critical interventions by tutors, so conveniently under-emphasised, flow quietly like electricity, to power school-branding

Many highly educated parents, however, trust their own credentials and experience more than the tutors’, to demonstrate essential topic-concepts to their children. They explain the underlying rationale and help the child make logical connections so often missing in school texts, or in the teacher’s instructions. Some parents perform like exceptional guru-teachers: they ensure that the child enjoys understanding truly and deeply the topic being taught. Such parents (often moms for elementary school), devote their entire evenings (specially during exam season) five days a week, tutoring their children.

Today it has become a norm to see our schools operate like (a) homework-manufacturing agencies and (b) testing and examination centres. During the interval between (a) and (b), much of the teaching-learning activities are conveniently outsourced to parents and private tutors.

The obvious question then is: what purpose are elite English medium schools serving if they can’t offer exam success or quality education?

Most elite Pakistani English medium schools appear to serve a higher purpose, one regarded as being far superior to education i.e. social networking. For pupils from age six and upwards, elite schools and their user-base ensure that the who’s who of Pakistan maintain their privileged status for generations. Fashionable school brands offer them the playground, halls, stage, and subsequently homes to intermingle and incubate long-term friendships. These will pay off one day as adult “connections” that allow fluid entry into lucrative high-end jobs, portals for marriages and keys to businesses. The accepted bottomline is: It’s social connections, not education, that counts.

While schools pocket fees together with undeserved credit for their students’ exceptional academic performance, parents dismiss their own tireless efforts nonchalantly with a shrug that seems to convey, what can’t be cured must be endured. Tutors, on the other hand, are content to be self-effacing as long as business is good. For them, the goal of education is to help students obtain spectacular grades in exams. In return, grateful schools deliver to them an unending stream of under-achievers every year.

The invaluable inputs from parents and critical interventions by tutors, so conveniently underemphasised, flow quietly like electricity, to power school-branding. Successful school brands grow on the back of the efforts of hard-working parents and tutors. But schools flash them like incandescent halos swimming above the heads of “their brilliant students”. It is ironic that parents rally around the halo because their personal stake in creating it lends a much-needed privilege status to their children’s school. Throughout the 12 long years of their school life, kids get to “go where it matters”.

It would be unfair to accuse schools, parents and tutors of any conscious complicity in setting up a seamless ecosystem generating a three-way conduit for distributing mutual benefits. An ecosystem does not thrive on complicity. It grows systemically and organically because of the intrinsic nature of the forces connecting them. Raising the value of “connections” over and above education, draws upon past experience. And most experiences flow out of values and beliefs in practice.

It is distressing that parents protest the upward spiral of school fees without demanding better education to show for it. If our children received the quality education they deserved exclusively from upscale schools, parents’ savings in supplementary tutoring would be substantial.

If schools promised quality education by asking for a small share of such savings, to invest in better courseware, teacher training, technology and greater, faster in-depth learning, parents would see their children enjoy exceptionally high levels of academic success. More importantly, exam success, and by corollary opportunities for future livelihoods, would no more be the exclusive preserve of those who can afford private tuition. It would extend to a much broader base of the student population, generating fierce completion and a genuine striving for academic excellence.

The cherry on the cake would be a refreshing new insight: that true and meaningful education, even without earning top grades, is preferable to one that is meaninglessly regurgitative but ornamented with star-studded grades.

Connecting the increase in school fees to the delivery of quality education makes more sense than schools charging more fees because they can. Or parents taking them to court for it simply because they can.

The writer is an Ed.M (Harvard), a member of the National Association of Mathematics Advisors UK and has also worked in Canada. He introduced Dyslexia and Math Learning Disabilities in Pakistan (1986) and set up the first Remedial Centre in Karachi (1987) (R.E.A.D.) @ShadMoarif