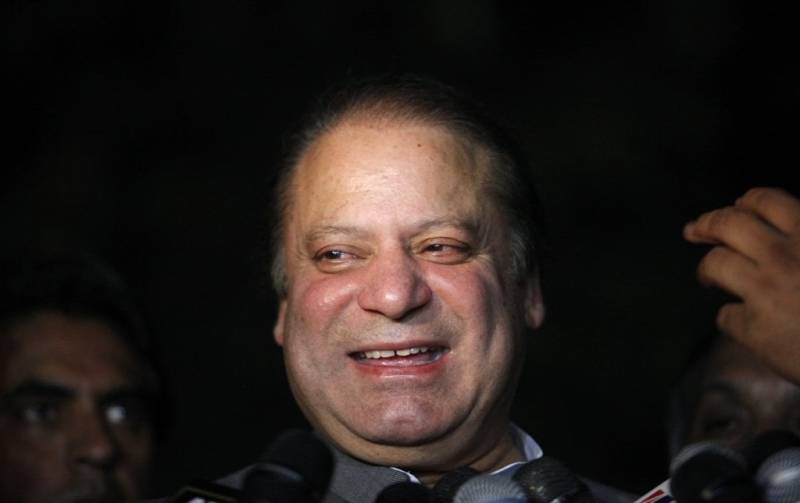

In the aftermath of the 2018 elections, few would have thought that Nawaz could make a comeback to the Prime Minister house. The hybrid regime’s latest experiment, built around the Naya Pakistan narrative and backed by the powerful military, was built off the back of excluding the three-time premier from Pakistan’s power corridors. Fast forward to today, and the opposite is materialising.

Despite many an appeal by PML-N’s cadre for Nawaz to return, the supremo has stayed put in London, to let his manoeuvring do the talking. It is clear that Nawaz has called major shots on the economy and politics from the comfort of his residence in London, rather than ending up in jail. Be it the appointment of General Asim Munir as the COAS, or sending Dar back as Finance Minister, Nawaz limited his role to navigating the muddy waters of Pakistan’s power politics.

The matter he has thus so far not taken up is to touch base with voters and assume command of the party’s rank and file. That is changing now. With PTI facing a disproportionate crackdown for the May 9 attacks and general elections on the horizon, Nawaz cannot pick a better time to return. The question then becomes: what does he have to offer this time round?

For a man whose party has not lost an election in Punjab since 1990, minus the one under Musharraf, it seems that delivering Punjab will be what he must offer. The challenge though, is bigger than before.

Unlike 2018, when the PML-N was riding a wave of popularity, 2023 is very different, not least because of skyrocketing inflation. Convincing scores of voters across Punjab and elsewhere to vote on performance alone will be next to impossible. Data across the board indicates that inflation has soared to previously unseen heights. Rising prices for the end consumer, dwindling foreign reserves and backbreaking commodity price inflation worsen that challenge.

Nawaz back on the campaign trail can mitigate the damage by pinning the blame on those who ousted him, but the average voter is unlikely to see beyond the price of daily commodities.

Then there are disgruntled voters, comprising a shrinking middle class and the youth, who refuse to believe traditional political class offers a solution to their woes. Winning over an entire generation raised on the unassailable idea that all, but one, are corrupt is an insurmountable challenge.

Young people form a significant chunk of the Pakistani electorate; people between 18 to 35 years old, numbering around 53.8 million – are the largest age bracket in the voter base, making up over 44% of total registered voters. Imran remains popular among this cohort, not least because he has empowered them with grandiose notions of ‘Haqeeqi Azadi.’ Khan also retains their sympathy, ever since he blamed the United States for unfairly conspiring with the establishment to oust him. It is unclear if Nawaz can overcome their opposition.

Despite all of the above, Nawaz back on the campaign trail will be potent in bringing dormant and on the fence voters to the voting booths. Invoking the PML-N’s anti-establishment narrative by targeting General (r) Bajwa, General (r) Faiz and members of the judiciary who schemed to remove him will sell in Punjabi heartlands, not least because these voters voted for PML-N in 2018 despite the Panama Conviction and blatant rigging. Going from town to town to recount the efforts by the judicial-military nexus to stage dharnas, disqualify him and rig the 2018 elections will be instrumental in activating his voter base in rural and urban Punjab. The recourse to ‘vote ko izzat dou’ will be required to shore up popularity. Nawaz has Imran to thank for having normalized criticizing the establishment; Imran Khan’s voter base is convinced that his ouster and the PTI’s dismemberment were coordinated by the military’s top brass. “Vote ko izzat dou” will also have intuitive appeal now across the electorate, and the PTI will either be forced to double down on its own establishment bashing, or back off for fear of inviting further displeasure, subsequently letting Nawaz occupy the same ideological space that Khan has so desperately sought to carve out for himself. Both situations bode well for PML-N's electoral chances.

Another role Nawaz is likely to play is assuming full command of the party. This has two dimensions. First, it means re-establishing connections with PML-N workers and organizers at all levels. The party’s middle and lower brass has long gravitated toward Nawaz, therefore restructuring the party to accommodate and reenergise local leaders is critical. It will also lead to optimal ticket distribution and activate voters on the ground. Second, competing factions within the PML-N must be dealt with. Be it Shahid Khaqan vying for an end to dynastic politics or Maryam Nawaz eyeing for a Chief Minister slot, Nawaz will have to settle key questions which will determine the future of the party and its unity, making them all the more important.

Perhaps, his most important contribution on arrival will be his perception of electability. Voters often tend to vote for leaders and parties on the ascendancy, as seen in many a prior election. Having mended ties with the military, Nawaz as a concrete Prime Ministerial candidate will aid PML-N ticket holders in several urban and rural constituencies in winning their seats.

But before he is back on the campaign trail, Nawaz must fight a legal battle which involves undoing his disqualification and conviction. There remains uncertainty over his candidature despite the Parliament’s bill limiting disqualification under Article 62 to 5 years. This battle will be fought in the hallowed hallways of the higher judiciary who are expected to set wheels in motion to hear his cases once the current Chief Justice retires.

For now, one thing is certain: Nawaz is coming.

Despite many an appeal by PML-N’s cadre for Nawaz to return, the supremo has stayed put in London, to let his manoeuvring do the talking. It is clear that Nawaz has called major shots on the economy and politics from the comfort of his residence in London, rather than ending up in jail. Be it the appointment of General Asim Munir as the COAS, or sending Dar back as Finance Minister, Nawaz limited his role to navigating the muddy waters of Pakistan’s power politics.

The matter he has thus so far not taken up is to touch base with voters and assume command of the party’s rank and file. That is changing now. With PTI facing a disproportionate crackdown for the May 9 attacks and general elections on the horizon, Nawaz cannot pick a better time to return. The question then becomes: what does he have to offer this time round?

For a man whose party has not lost an election in Punjab since 1990, minus the one under Musharraf, it seems that delivering Punjab will be what he must offer. The challenge though, is bigger than before.

Unlike 2018, when the PML-N was riding a wave of popularity, 2023 is very different, not least because of skyrocketing inflation. Convincing scores of voters across Punjab and elsewhere to vote on performance alone will be next to impossible. Data across the board indicates that inflation has soared to previously unseen heights. Rising prices for the end consumer, dwindling foreign reserves and backbreaking commodity price inflation worsen that challenge.

Nawaz back on the campaign trail can mitigate the damage by pinning the blame on those who ousted him, but the average voter is unlikely to see beyond the price of daily commodities.

Then there are disgruntled voters, comprising a shrinking middle class and the youth, who refuse to believe traditional political class offers a solution to their woes. Winning over an entire generation raised on the unassailable idea that all, but one, are corrupt is an insurmountable challenge.

The recourse to ‘vote ko izzat dou’ will be required to shore up popularity.

Young people form a significant chunk of the Pakistani electorate; people between 18 to 35 years old, numbering around 53.8 million – are the largest age bracket in the voter base, making up over 44% of total registered voters. Imran remains popular among this cohort, not least because he has empowered them with grandiose notions of ‘Haqeeqi Azadi.’ Khan also retains their sympathy, ever since he blamed the United States for unfairly conspiring with the establishment to oust him. It is unclear if Nawaz can overcome their opposition.

Despite all of the above, Nawaz back on the campaign trail will be potent in bringing dormant and on the fence voters to the voting booths. Invoking the PML-N’s anti-establishment narrative by targeting General (r) Bajwa, General (r) Faiz and members of the judiciary who schemed to remove him will sell in Punjabi heartlands, not least because these voters voted for PML-N in 2018 despite the Panama Conviction and blatant rigging. Going from town to town to recount the efforts by the judicial-military nexus to stage dharnas, disqualify him and rig the 2018 elections will be instrumental in activating his voter base in rural and urban Punjab. The recourse to ‘vote ko izzat dou’ will be required to shore up popularity. Nawaz has Imran to thank for having normalized criticizing the establishment; Imran Khan’s voter base is convinced that his ouster and the PTI’s dismemberment were coordinated by the military’s top brass. “Vote ko izzat dou” will also have intuitive appeal now across the electorate, and the PTI will either be forced to double down on its own establishment bashing, or back off for fear of inviting further displeasure, subsequently letting Nawaz occupy the same ideological space that Khan has so desperately sought to carve out for himself. Both situations bode well for PML-N's electoral chances.

Another role Nawaz is likely to play is assuming full command of the party. This has two dimensions. First, it means re-establishing connections with PML-N workers and organizers at all levels. The party’s middle and lower brass has long gravitated toward Nawaz, therefore restructuring the party to accommodate and reenergise local leaders is critical. It will also lead to optimal ticket distribution and activate voters on the ground. Second, competing factions within the PML-N must be dealt with. Be it Shahid Khaqan vying for an end to dynastic politics or Maryam Nawaz eyeing for a Chief Minister slot, Nawaz will have to settle key questions which will determine the future of the party and its unity, making them all the more important.

Perhaps, his most important contribution on arrival will be his perception of electability. Voters often tend to vote for leaders and parties on the ascendancy, as seen in many a prior election. Having mended ties with the military, Nawaz as a concrete Prime Ministerial candidate will aid PML-N ticket holders in several urban and rural constituencies in winning their seats.

But before he is back on the campaign trail, Nawaz must fight a legal battle which involves undoing his disqualification and conviction. There remains uncertainty over his candidature despite the Parliament’s bill limiting disqualification under Article 62 to 5 years. This battle will be fought in the hallowed hallways of the higher judiciary who are expected to set wheels in motion to hear his cases once the current Chief Justice retires.

For now, one thing is certain: Nawaz is coming.