American mathematician John Allen said, “Uncertainty is the only certainty”. By this, I think, he meant that humans can only speculate and theorise based on their experiences but at any point in time, things can change. For instance, a day might come when the sun rises out of the west, however unlikely that may sound. However, there’s another certainty. It goes like this:

“I know this person. There is absolutely no chance they can change. The only way the world will ever be a better place will be if we kill this person”

In other words, the Death Penalty. When the devil was ‘charged for refusing to bow to Adam, he was ‘condemned to hell; he wasn’t sent on death row. The punishment for the gravest of sins is repentance, in this life or the subsequent, not murder. The underlying foundational assumption being that everyone, no matter how good or bad, can change.

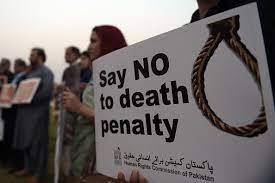

So this raises an important question. How can we as human beings develop systems and laws that grant us the right to go against such foundational principles i.e. repentance? Pakistan is one of the fifty-five states that still recognise the death penalty as a legitimate form of punishment for certain crimes; 33 to be exact.

According to the report of Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), by October 2022, there were 3226 condemned prisoners in Pakistan with 2296 in Punjab, 514 in Sindh, 355 in KP, and 61 in Balochistan. Since 2019, there have been no reported cases of death penalty execution being carried out but that does not mean that executions would not be carried out in the future as there are currently 1144 prisoners with rejected Supreme Court appeals.

It is not just the state of Pakistan that is retentionist (keeping the death penalty intact), many people too, regardless of their political, religious and spiritual beliefs, support the death penalty or rather actively advocate for it. During one of the previous high profile murder cases, there was an outpouring call for the convict to be hanged publicly (the convict did end up with death penalty punishment, however it has not been carried out yet). In another high profile rape case, people, including the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, suggested chemical castration of the convict.

When a prisoner is executed, the story does not end there. Let’s assume for a second that the convict is a married man and father to a few children. We not only take away a life, we take away Children’s right to a father, parents’ right to a son, wife’s right to a husband. Therefore, the act of taking away a life not only affects one person but rather a whole family. The parents, children and spouses suffer from a trauma which, perhaps, none of us would have the emotional quotient to emphathise with. This does not imply, by any means, that the convict or criminal be set free.

Furthermore, there have been studies that suggest that death penalty is not really as powerful a crime deterrent as imprisonment. The crime rates, as per the JPP report, has not varied much despite death sentences being awarded to the offenders. The idea of punishment for crime, the imprisonment process and prisons themselves all requires reflection. Dehumanisation and taking away the right to life is no solution to a dehumanising crime. There’s a saying that goes “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.”

Be it life imprisonment or death penalty, the end goal of both is to ensure the convict does not have the ability or means to commit a similar or worse crime again for as long as he/she lives. Imprisonment does it by means of confining a person in the physical boundaries of tougher laws, and stricter controlling measures while death penalty is simply the act of taking away a life. Furthermore, one operates on the underlying assumption that the convict may at some point, turn to repentance and may regret their actions while the other doesn’t.

Pakistan must, therefore, look hard on its stance on death penalty and maybe rethink the position on the 33 crimes it deems heinous enough to take away a person’s right to life which includes, kidnapping for ransom, mutiny, murder (qatl e amad) or, may I dare say, 295C.

“I know this person. There is absolutely no chance they can change. The only way the world will ever be a better place will be if we kill this person”

In other words, the Death Penalty. When the devil was ‘charged for refusing to bow to Adam, he was ‘condemned to hell; he wasn’t sent on death row. The punishment for the gravest of sins is repentance, in this life or the subsequent, not murder. The underlying foundational assumption being that everyone, no matter how good or bad, can change.

So this raises an important question. How can we as human beings develop systems and laws that grant us the right to go against such foundational principles i.e. repentance? Pakistan is one of the fifty-five states that still recognise the death penalty as a legitimate form of punishment for certain crimes; 33 to be exact.

According to the report of Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), by October 2022, there were 3226 condemned prisoners in Pakistan with 2296 in Punjab, 514 in Sindh, 355 in KP, and 61 in Balochistan. Since 2019, there have been no reported cases of death penalty execution being carried out but that does not mean that executions would not be carried out in the future as there are currently 1144 prisoners with rejected Supreme Court appeals.

It is not just the state of Pakistan that is retentionist (keeping the death penalty intact), many people too, regardless of their political, religious and spiritual beliefs, support the death penalty or rather actively advocate for it. During one of the previous high profile murder cases, there was an outpouring call for the convict to be hanged publicly (the convict did end up with death penalty punishment, however it has not been carried out yet). In another high profile rape case, people, including the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, suggested chemical castration of the convict.

When a prisoner is executed, the story does not end there. Let’s assume for a second that the convict is a married man and father to a few children. We not only take away a life, we take away Children’s right to a father, parents’ right to a son, wife’s right to a husband. Therefore, the act of taking away a life not only affects one person but rather a whole family. The parents, children and spouses suffer from a trauma which, perhaps, none of us would have the emotional quotient to emphathise with. This does not imply, by any means, that the convict or criminal be set free.

Furthermore, there have been studies that suggest that death penalty is not really as powerful a crime deterrent as imprisonment. The crime rates, as per the JPP report, has not varied much despite death sentences being awarded to the offenders. The idea of punishment for crime, the imprisonment process and prisons themselves all requires reflection. Dehumanisation and taking away the right to life is no solution to a dehumanising crime. There’s a saying that goes “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.”

Be it life imprisonment or death penalty, the end goal of both is to ensure the convict does not have the ability or means to commit a similar or worse crime again for as long as he/she lives. Imprisonment does it by means of confining a person in the physical boundaries of tougher laws, and stricter controlling measures while death penalty is simply the act of taking away a life. Furthermore, one operates on the underlying assumption that the convict may at some point, turn to repentance and may regret their actions while the other doesn’t.

Pakistan must, therefore, look hard on its stance on death penalty and maybe rethink the position on the 33 crimes it deems heinous enough to take away a person’s right to life which includes, kidnapping for ransom, mutiny, murder (qatl e amad) or, may I dare say, 295C.