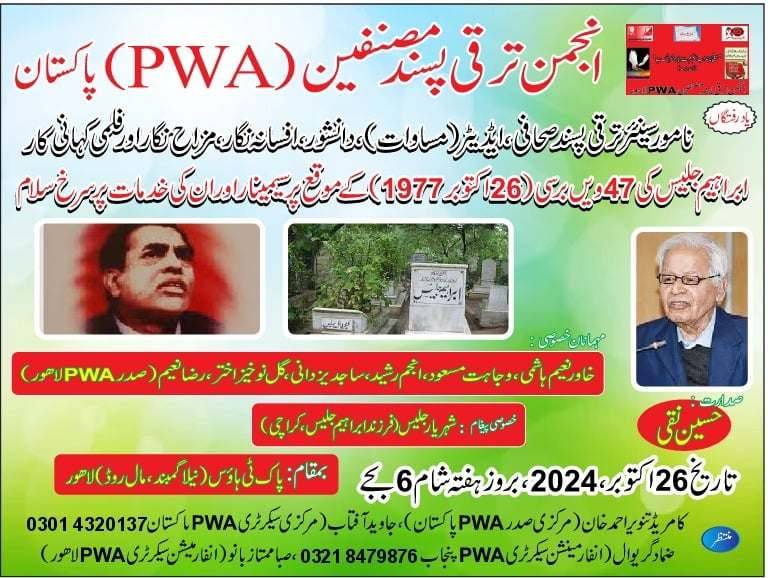

Today is the 47th death anniversary of Ibrahim Jalees, who fought for the Razakars against the Indians in Hyderabad Deccan and for Pakistani comrades in Karachi, who became entangled in the infamous Public Safety Act and went to jail for five months, who was one of the first journalists to visit Maoist China, who was the editor of Musawat, who wrote satire and short-stories and became a celebrated journalist in his own right.

An important proof of Ibrahim Jalees (1924 – 1977) as perhaps one of the few true crusading journalists in Pakistan’s history is to be had when one reads the incendiary sketch of the man – titled Dakkan ka Tohfa (Gift of the Deccan) – by the writer Hameed Akhtar, in his book Aashnaiyan Kya Kya (Various Acquaintances).

Here, the portraits of the policies of our initial governments with reference to the Public Safety Act and censorship are a testimony; such a testimony of history that, despite being before us, is invisible. It thus has the status of an authority for any historian who compiles our political or literary history, and can aid him or her in doing so.

"Even before the creation of Pakistan, he had been acknowledged as the representative short-story writer of the new young generation"

A fresh re-reading of this sketch on the occasions of the birth centennial of its protagonist Ibrahim Jalees, his 47th death anniversary today and the birth centenary of the writer Hameed Akhtar (incidentally he also passed away in October) may thus not only be necessary but inevitable.

***

Today in the beginning of 1992, when I am sitting writing these lines, thirteen years have passed since Ibrahim Jalees separated from us, after his sudden death the critics, publishers and perhaps readers of literature too have forgotten him. This was not his age to die, he was hardly 55 years old at the time of death, maybe even younger. Why was such a careless and apparently free person in a hurry to leave? How did he die? He never contracted heart disease. Then suddenly one day how did his weak heart stop working? This and many other questions emerge in the mind about which we will talk afterwards although this matter is certainly noteworthy that why did the readers of literature, friends and fans of a progressive short-story writer and the successful columnist subsequently forget him? He was an extremely mischievous prose-writer, he wrote a lot too, his short-stories and other writings possessed astonishing tartness, even before the creation of Pakistan he had been acknowledged as the representative short-story writer of the new young generation.

Now perhaps people have very much even forgotten that who was he, what was he, although many people among his contemporaries are still alive. The readers of the new generation (whose quantity is getting smaller daily anyways) don’t even know how much attractive a personality he possessed, how he lived, wherefrom he came, what were his habits of conversation, debate and everyday life. This may not be the problem of the reader of literature, but it is definitely the duty of those who knew him and spent some time in his company that they preserve some remains of his beloved personality.

Jalees had a height of 6 feet and complexion was a bit dark, features were very sharp and eyes full of intelligence. If he was present in any gathering, he would give very little opportunity to others to speak rather it would be proper to say that nobody could even dare to speak in his presence. He spoke tirelessly and would keep adding similes, metaphors, jokes and witticisms in his conversation, at that time he would appear to be the most beautiful man in the world. Both of us remained with each other in Lahore for a long time in a state of destitution. Despite hunger, thirst, pennilessness and poverty this was the golden period of our life which will be remembered till the last breath. In his presence no problem seemed like a problem, no problem could overcome us, however the circumstances maybe, he would laugh himself too and would keep making others laugh as well, after this such company was never attained. With him, we bore starvation happily, he was a cheerful man in the true sense. In the uncertain conditions of those days meaning right after the creation of Pakistan his personality was an excuse for us friends to stay alive.

Arrival in Bombay

Sahir Ludhianvi was already a captive of the magic of his personality. When he returned to Ludhiana after participating in the conference of the Progressive Writers in Hyderabad Deccan in 1944-45, there was only one name he remembered all the time and that name was of Jalees, although all the big names of the subcontinent had participated in that conference; those whose writings we were reading with veneration. During this same conference Sahir met Krishan Chander, Ismat Chughtai, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Kaifi Azmi, Sardar Jafri and Sajjad Zaheer himself. But Jalees had pleased him a lot. His first collection of short-stories Chalees Kadod Bhikari (400 Million Beggars) had been published, his writings were full of poison-coated sarcasm. When both of us reached Bombay in January 1946 after being connected to the film world, Sahir called Jalees as a dialogue-writer from Hyderabad to Bombay by tempting the financer. Among the dialogue-writers of Hindustan Kala Mandir’s film Azadi Ki Raah Par (On the Road of Freedom), Mahmud Barelvi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Hajra Masroor and myself were already present, now the name of Ibrahim Jalees was added to this list. Upon getting the information of his arrival when we reached the railway station of Bombay and Sahir Ludhianvi embraced a very lean and lanky youth of tall height I was extremely disappointed. He was not only wearing a sherwani with an Aligarh-cut pyjama rather had also set a Turkish cap on the head, this youth appeared to me to be a very uncouth thing but while reaching the flat in Suleman Chambers in Colaba in which we lived his whole personality had become clear in front of us. He would talk himself and then fully burst out laughing. To make an argument and playing with words was confined to him.

The next day Jalees too participated in our meeting which in film terminology is called sitting over the story. After a formal introduction discussion began on various scenes of the film and their dialogues. The financer Kalwant Rai was very habitual of speaking English, he began to speak in English in the heat of discussion. Then stopping suddenly he asked Jalees. ‘Mr Jalees do you understand English?’

‘Yes’, Jalees gave a brief answer.

After about half an hour the financer once again stopping his speech in English began to ask, ‘Mr Jalees you do understand English right?’

‘Sir! What do you want to say? I have passed BA from Aligarh.’ This time his tone was a bit harsh. The financer had no doubt that he is acquainted with the mysteries and symbols of the English language.

That day the title scene of the film was being discussed, how the title of the film should appear on the screen, a lot of suggestions were presented on this which were rejected one after another. At the end, the financer accepted his own suggestion that a cannon should be seen on the whole screen, after that the cannon should be fired by turning the direction of its barrel and instead of the cannon-ball a book should emerge from it to come on the screen on which ‘On the Road of Freedom’ should be written in bold letters.

All of us were sick of the discussion, the idea too was the financer’s own so that not only did everyone acknowledge it rather applauded it as well. But Jalees remained silent. When all of the remaining people became silent then Jalees while addressing the financer said, ‘Mr Kalwant! From the descent of Adam to this day, has a book ever emerged from the barrel of a cannon?’

Nobody had an answer to that, this suggestion too was rejected, however the financer definitely did have to ask the meaning of the descent of Adam two to three times.