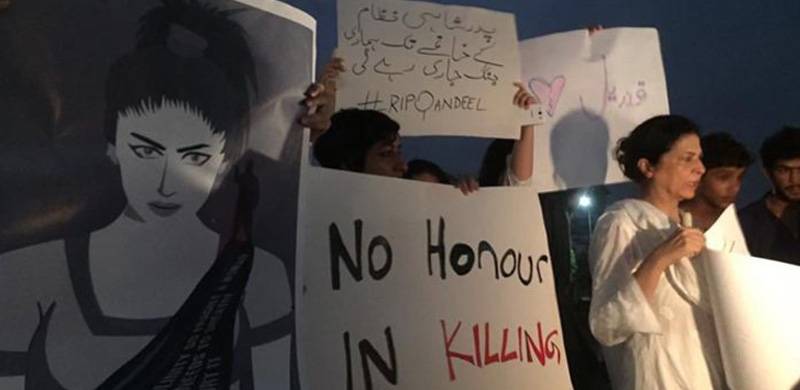

There are many ways to condone violence against women. For the murder of social media star Qandeel Baloch, the Lahore High Court, ruling on the appeal by her brother Muhammad Waseem, acquitted the accused based on three reasons: first, that his confession before the court was not voluntary; secondly, that the court’s power to reject compromises between parties applies only when the accused is sentenced under qisas, while Waseem is sentenced under ta’zir; and thirdly, because the accused’s stated motive for murder was not honour. While the first two reasons deserve a separate discussion, the third reason evokes curiosity. The Court ruled that the accused had stated that he murdered his sister due to her objectionable pictures and videos, not on the pretext of honour. The difference between the two is not discussed by the Court.

Offensive as this may seem, this is also the Court’s way of distinguishing Qandeel’s murder from the purpose of the most recent set of amendments to Pakistan Penal Code, 1860. These amendments, passed in 2016, empower courts to reject compromises between parties to a murder trial, and mandates a minimum sentence of life when a crime is perpetrated on the ‘pretext of honour’. Therefore, by stating that Waseem murdered his sister on grounds other than honour, this judgement carves an exception to this latest set of amendments. This may set a dangerous precedent where courts in future go into needless technicalities of what constitutes a murder based on honour. This may allow courts to accept compromises more readily for such murders, although the discretion of courts to reject compromises exists in every case.

As a social concept, murders on the pretext of honour or ghairat have no singular definition. Globally, Purna Sen points out, honour crimes include varied violence like stove burnings, violence in response to free will marriages, dowry crimes and violence resulting from failure to perform domestic duties. Lawmakers and courts alike would therefore be ill-advised to attempt to come up with a singular definition.

This judgement, now pending appeal before the Supreme Court, is only the latest judgement of the higher court of Pakistan that creates a dent in legislation that aims to address loopholes concerning honour killings. Another is the Muhammad Qasim case, decided by the Supreme Court in 2018, and authored by Justice Khosa, which represents the culmination of a long line of judgements that uphold another exception, based on murders that are provoked. In this case, a man murdered his sister-in-law and her alleged lover in broad daylight upon allegedly finding them in an amorous position in a field. The court held that crimes on the pretext of honour are premeditated, while this was a case where the accused flew into a rage upon seeing his female relation in this position. As a result, his sentence was reduced to 20 years imprisonment from the earlier life sentence. Pakistani court’s continued preservation of the partial defence of ‘grave and sudden provocation’ is a peculiar exercise of judicial function.

Prior to 1989, our laws, like much of the world, treated ‘grave and sudden provocation’ as a mitigating circumstance when sentencing people for murder. The provocation principle finds its roots in the 16th and 17th century England, where dignified men were expected to react with ‘controlled violence’ to physical violence and affronts to their dignity. Among these affronts to their dignity was the act of seeing the wife committing adultery. As ‘controlled violence’ could sometimes spill into causing death, the law had to be flexible enough for that eventuality. By the 19th century, the standard evolved, and the accused was subjected to a reasonable man standard. This required, for example, that there be no ‘cooling off period’ between learning of the adultery and the murder.

In Pakistan, the ground of provocation was struck down by the Gul Hassan case in 1989 for not being recognized in Islam. However, as early as 1992, courts began to revive provocation as a mitigating circumstance, stating that a trespasser to the home cannot be protected even under Islamic principles, let alone one who indulges in contact with a na-mehram woman. In a long line of cases, the provocation principle was also expanded to cover attacks on not just adulterous wives or their alleged paramours, but also sisters, cousins and as with the 2018 Muhammad Qasim case, sisters-in-law. Sadly, there is also little consideration for applying an objective reasonable person standard to crimes. In one case, the accused’s Pashtun sensibilities were among the reasons for him flying into a murderous rage at merely verbal insults about the women of his tribe. The 16th century English standard painted the picture of one conception of masculinity, Pakistani courts here answered to the needs of a particularly South Asian masculinity.

Legislative amendments concerning honour crimes in Pakistan have so far narrowly focused on increased sentencing, and strengthening courts’ ability to reject compromises between the accused and heirs of the deceased. No doubt, none of these have been watertight. The Muhammad Qasim case, certainly following a long line of cases on provocation, and the decision in Qandeel Baloch’s murder, create further weaknesses in these amendments. But the roots of honour killings remain social. One therefore cannot expect the police, prosecutors and judges to remain unaffected by these social influences. We must look beyond the seemingly objective role of the law to understand, and subsequently dismantle, these gendered understandings as they crop up in our systems.

Authors Note: I presented a different topic at the Conference held at LUMS on April 16, 2022, regarding the jurisprudence of Justice (R) Asif Khosa. The presentation was a working paper that I intend to publish in an academic journal. Academic publishing requires that a submitted paper cannot have been published elsewhere, such as in this magazine. Here, I present a different, but related article on honour crimes jurisprudence in Pakistan.

The author teaches law at the Shaikh Ahmad Hassan School of Law, LUMS.

Offensive as this may seem, this is also the Court’s way of distinguishing Qandeel’s murder from the purpose of the most recent set of amendments to Pakistan Penal Code, 1860. These amendments, passed in 2016, empower courts to reject compromises between parties to a murder trial, and mandates a minimum sentence of life when a crime is perpetrated on the ‘pretext of honour’. Therefore, by stating that Waseem murdered his sister on grounds other than honour, this judgement carves an exception to this latest set of amendments. This may set a dangerous precedent where courts in future go into needless technicalities of what constitutes a murder based on honour. This may allow courts to accept compromises more readily for such murders, although the discretion of courts to reject compromises exists in every case.

Globally, Purna Sen points out, honour crimes include varied violence like stove burnings, violence in response to free will marriages, dowry crimes and violence resulting from failure to perform domestic duties. Lawmakers and courts alike would therefore be ill-advised to attempt to come up with a singular definition.

As a social concept, murders on the pretext of honour or ghairat have no singular definition. Globally, Purna Sen points out, honour crimes include varied violence like stove burnings, violence in response to free will marriages, dowry crimes and violence resulting from failure to perform domestic duties. Lawmakers and courts alike would therefore be ill-advised to attempt to come up with a singular definition.

This judgement, now pending appeal before the Supreme Court, is only the latest judgement of the higher court of Pakistan that creates a dent in legislation that aims to address loopholes concerning honour killings. Another is the Muhammad Qasim case, decided by the Supreme Court in 2018, and authored by Justice Khosa, which represents the culmination of a long line of judgements that uphold another exception, based on murders that are provoked. In this case, a man murdered his sister-in-law and her alleged lover in broad daylight upon allegedly finding them in an amorous position in a field. The court held that crimes on the pretext of honour are premeditated, while this was a case where the accused flew into a rage upon seeing his female relation in this position. As a result, his sentence was reduced to 20 years imprisonment from the earlier life sentence. Pakistani court’s continued preservation of the partial defence of ‘grave and sudden provocation’ is a peculiar exercise of judicial function.

Prior to 1989, our laws, like much of the world, treated ‘grave and sudden provocation’ as a mitigating circumstance when sentencing people for murder. The provocation principle finds its roots in the 16th and 17th century England, where dignified men were expected to react with ‘controlled violence’ to physical violence and affronts to their dignity. Among these affronts to their dignity was the act of seeing the wife committing adultery. As ‘controlled violence’ could sometimes spill into causing death, the law had to be flexible enough for that eventuality. By the 19th century, the standard evolved, and the accused was subjected to a reasonable man standard. This required, for example, that there be no ‘cooling off period’ between learning of the adultery and the murder.

In Pakistan, the ground of provocation was struck down by the Gul Hassan case in 1989 for not being recognized in Islam. However, as early as 1992, courts began to revive provocation as a mitigating circumstance, stating that a trespasser to the home cannot be protected even under Islamic principles, let alone one who indulges in contact with a na-mehram woman. In a long line of cases, the provocation principle was also expanded to cover attacks on not just adulterous wives or their alleged paramours, but also sisters, cousins and as with the 2018 Muhammad Qasim case, sisters-in-law. Sadly, there is also little consideration for applying an objective reasonable person standard to crimes. In one case, the accused’s Pashtun sensibilities were among the reasons for him flying into a murderous rage at merely verbal insults about the women of his tribe. The 16th century English standard painted the picture of one conception of masculinity, Pakistani courts here answered to the needs of a particularly South Asian masculinity.

Legislative amendments concerning honour crimes in Pakistan have so far narrowly focused on increased sentencing, and strengthening courts’ ability to reject compromises between the accused and heirs of the deceased. No doubt, none of these have been watertight.

Legislative amendments concerning honour crimes in Pakistan have so far narrowly focused on increased sentencing, and strengthening courts’ ability to reject compromises between the accused and heirs of the deceased. No doubt, none of these have been watertight. The Muhammad Qasim case, certainly following a long line of cases on provocation, and the decision in Qandeel Baloch’s murder, create further weaknesses in these amendments. But the roots of honour killings remain social. One therefore cannot expect the police, prosecutors and judges to remain unaffected by these social influences. We must look beyond the seemingly objective role of the law to understand, and subsequently dismantle, these gendered understandings as they crop up in our systems.

Authors Note: I presented a different topic at the Conference held at LUMS on April 16, 2022, regarding the jurisprudence of Justice (R) Asif Khosa. The presentation was a working paper that I intend to publish in an academic journal. Academic publishing requires that a submitted paper cannot have been published elsewhere, such as in this magazine. Here, I present a different, but related article on honour crimes jurisprudence in Pakistan.

The author teaches law at the Shaikh Ahmad Hassan School of Law, LUMS.