Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times

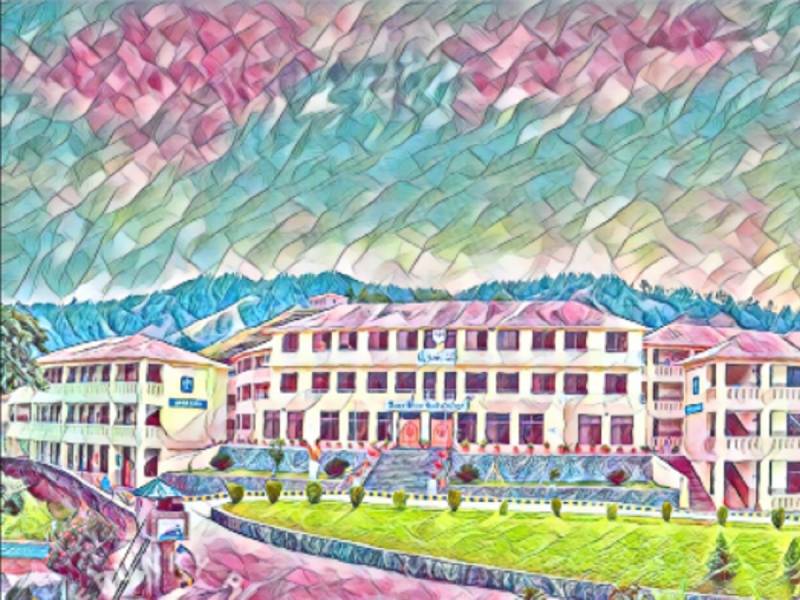

A convenient time to start this account of my boyhood—from the age of ten to that of eighteen—is when I was sent to study in Senior Burn Hall school in March 1960. I remember how I was taken there by my father on a local bus plying between Abbottabad and Mansehra on a fine spring evening. The school of red brick looked imposing from the long tree-lined drive. In the middle of the huge playing fields was a sparkling canal in which I could see seaweed. Later I discovered there were fish too but at that time we were walking too fast to see them. We were met by an Englishman, a man with the rounded white collar of a priest, who led us to some chairs laid out for our interview. I did not understand what he asked my father but he admitted me. This was my first meeting with the Reverend Father Scanlon, the formidable Principal of Senior Burn Hall. The classes started and I prided myself on studying French and a book on biology which actually talked of reproduction. I told Tariq Ahsan, with an air of grown-up secrecy, that such books were not good for ‘little children’. Unfortunately, he was not impressed.

I generally stayed out of doors in the early sixties when I studied in Burn Hall and lived in the hut next to the main PMA road. This hut still stands—one of the few which do—but there is a small mosque in what used to be its lawn. In the school I had to attend classes but we had two breaks during which we rushed out to play marbles, catch Father Johnson’s fish from the canal or the pond and climb the hill behind the school. The hill had no trees at that time but it did have high grass where we rolled about. I loved to talk to Father Dolen, an old white-haired priest, who had many stories for eager conversationalists. I also liked the handsome Father Doyle who was Irish and still said book with a long ‘o’ which rhymed with the ‘o’ sound in ‘cool’ and ‘soup’. He taught us English and world geography and really spent considerable effort on us though he was rather boring as a teacher. Miss Manto, a spinster, taught us arithmetic and I never found anyone as painstaking as she was. She gave us homework and made it a point to check it and she would get very irritated, I now understand why, when she explained the mysteries of ‘vulgar fractions’ while we read comics under the table. French was taught by Father Trepstra (that is what we thought his name was) who was French. He had a reputation of giving benders—one kneeled against the table and was beaten on the bottom with a cane—but I do not remember having been punished by him. Indeed, the benders were rare but their fear was ubiquitous.

Burn Hall was an easy-going sort of school. Classes began at 8:30 and, even with the two breaks, classes were off at 1:20. Saturday was a half-holiday when we broke up at 10:30. In the summer, after the mid-term examination in June, we had one month’s summer break. In the winter, after the final examination in November, we had our three month’s winter vacation. We were not given any new books before the winter holidays so that we could enjoy those three months to our hearts’ content. In the spring, at Easter, we had about a week’s leave. This, however, was shortened sometimes. Then there were innumerable saints’ days and, of course, all Muslim and national holidays. In fact, in my school days, we also had holidays for Hindu festivals (Holi and Diwali) and basant (common to all Punjabis) and Christmas was called Christmas and not Quaid-e-Azam’s birthday. The state did not say that Christmas was only for Christians and my father told me that Christ, Hazrat-e-Isa, was revered by Muslims as a prophet of God hence, at least in my mind, Christmas was a festive occasion. Not all teachers gave us home work so that we had a lot of time to play. The teachers were very autonomous as far as we could make out. They had their distinct styles of teaching and not all were good. Some were very good, however. This is true in all schools even now though the modern fashion is to give less autonomy to them. Nobody ever came to the classes to observe them nor did our teachers have to submit our notebooks to the headmaster. Incidentally, Father Scanlon styled himself ‘headmaster’ and not ‘principal’. The teachers made no planners nor did they have to write reports on us. So, they felt very independent and not like the inferior hirelings of the principal, or the owners of the school, as teachers do in the elite English-medium schools of Pakistan today. Father Scargon, for instance, told us stories. He had a knack for drama and would walk and talk as if he was acting in a drama. Father Johnson came to the class shouting ‘Lal! Lal!’ and wrote difficult English words on the blackboard. We were supposed to learn them. He called them Johnsonese and I, at least, did not know that this referred to Dr. Samuel Johnson and not Father Johnson. He also made us read out Sir Rider Haggard’s novels. The characters appealed to us so much that we went around calling each other Gagool, Umslopagaas and Alan Quartermain. Both did not bother much about checking notebooks yet they did give us essays which most of us did write since we were afraid of being caught. I believe that regimented institutions of these days could not tolerate teachers of this kind—and what a loss it is! With so much freedom some teachers did shirk work but every system has casualties. I believe it is better if the system puts up with some shirkers rather than make all teachers lose their independence, freedom and self-respect. Anyway, I am digressing.

The school had a huge dining hall with yellow painted windows on three sides so that it was bright and airy. There was a raised dais, the equivalent of the Oxbridge high table, on which was the dining table for the priests. The boarders sat on tables according to their houses—Saint Michael and Saint Gabriel—and one boy had to read something at the meals. The day scholars too had to recite poetry so that we got our pronunciation corrected by each other and the priests. The meals were served by smartly dressed waiters and there were gardeners to tend to the lawns, the grounds and the gardens in the huge campus. However, apart from these people, there was only the driver, Majeed, and the man-of-all-errands, Ghulam. There were no clerks. Father Scanlon did his own typing. There was nobody to collect the fees. Father Ford, who taught us mathematics in senior classes, collected the fees as did some other priests too. Nor did anybody run the canteen except Father Doyle who, assisted by a boy, opened the canteen during the break. All books, notebooks, ties, belts, badges, buttons for blazers and other little things were sold during these breaks or on Saturday. In short, unlike nowadays, the priests ran the school with as little hired underlings as possible. I suppose no ‘principal’ worth their name would imagine not having a PA to answer the phone nowadays but Father Scanlon did not. And Father Scanlon actually taught geography to senior classes. There was nobody who did not teach. There was no such thing as a separate ‘administrative cadre’ or ‘management’ which did not teach as one finds in most schools now.

The school had some animals in residence too. There was the donkey who leveled the hockey ground. Patiently he went from end to end with the heavy roller behind him while a mali kept nudging him if he slackened down. There was also a dog but he was no longer young so he did not deign to notice small boys unless they actually touched him. There were, of course, Father Johnson’s gold fish in the pond and the well. The well was a mysterious place in the garden which contained the pond and was supposed to be very deep. It was, however, a shallow little hole in the ground and not really a well at all. The water in it did not come from the ground but through a tap. Such unromantic facts were unknown to us when we were in the junior classes. And, how could I forget them, there were swans in the pond with the lotus flowers. And in the middle of the pond was a little island with wild flowers and much greenery. In the midst of it stood a coop with pigeons which fluttered around the boys when they threw crumbs to them. I also remember ducks but I do not remember how long they lasted. The school had a swimming pool and tennis courts as well as grounds for other games but day scholars seldom attended games so I never played in them.

In time I came to have many friends. Among them were, of course the childhood ones, Javed Athar and his sisters (Ghazala, Rizwana and Rakhshan), Javed’s cousins, Mr. Bhatti’s daughters, Raheela (Kuku ) and Nazia (Reeno). I also remember, though vaguely, an English girl Teena Cock (yes, this was her name) and someone called Reeta. But the last two were with us when I lived in one of the first two huts so I am probably mixing them up with the girls who played with us when we were young teenagers. Lieutenant (later major) Sultan Hussain Shamsie was posted to PMA sometime in 1961 and his sons, Khalid and Abid, also became my friends. At the same time came Major (later colonel) Dildar Rana’s son Gulzar Rana also became a friend. He had a younger brother, Zulfikar (Zulfie) whom I met later also when he was a Lt. Col in the army but at that time he was too young to play with me. In late 1961 perhaps Brigadier (later major general) Mohammad Rafi Khan was posted as the commandant of PMA. His children, Shaheen, Shahla (called Shala) and Shahrukh became our playmates.

What I loved most by way of sports was riding horses. I became bolder and bolder in riding and later rode without a saddle which was called ‘bareback riding’, chasing dogs on horseback and playing a game in which the rider with the handkerchief was chased till he gave up the handkerchief. This was a gentler form of what the Afghans call Buz Kushi. Moreover, I also began show jumping which was generally not allowed to officers’ children. In time I also went out for riding outside the riding school and the polo ground. This was called cross country rides. I still remember once going to Kalapani on horses with Dafadar (or Ustad as we called him) Gakkhar. Javed, Khalid and myself were chosen for this adventure and we felt very grownup. I was reputed to be a good rider so I was often entrusted with others whom I could take cross country though one of the staffs, an NCO of the RVFC, was always with us. One particularly long and adventurous cross country ride I remember in which, besides the usual suspects—Javed, Khalid, Gulzar, Shaheen and Shahrukh—we were joined by Shala and one other girl whom I do not remember. We went behind the mountains behind Burn Hall into a narrow ravine which had treacherous roots and puddles so that the horses slipped and stumbled. The NCO with us was worried about our safety and the horses refused to stand still or walk gently. Eventually we turned around and found our way back.

Riding, and especially riding unruly horses added to my prestige as children tend to value such things. In time I became so fond of riding and so good at it that I was the undisputed best rider among the children. Indeed, the adjutant, Major (later Lt. General) Ahmad Kamal Khan gave me a certificate to the effect that I was a fearless rider and could handle all types of horses. This was because I sought out difficult horses and tamed them. One of these, Horse No. 39 believe, had a reputation of throwing riders and injuring them. The riding instructors, all NCOs of the RVFC who were horse trainers, were afraid of riding him. I took him and, though he bucked and reared, tamed him till he broke into a gallop. I made him gallop around in a circle and then, when he got exhausted, brought him back where the riders and the instructors waited to greet me with admiration.

I also loved climbing mountains. Our most favourite climb was the Gurkha Hill, the nearest mountain behind the village near PMA which was called Padara which, if I remember correctly, was a short or informal version of Aspadar. Then there was the little mosque on the mountain behind Kakul which I had first climbed alone. And attached to this mosque are probably some of the most precious memories of my boyhood. I remember a trip there when it had snowed probably in 1963. I distinctly remember that Javed Athar, Khalid Shamsie, Abid Shamsie, Shaheen, Shahrukh and Shala were certainly there. Perhaps Ghazala, Reeno and Kuku were also there but this I am not sure of. It was cold and the snow sparkled as the valley lay as if bathed in golden sunshine and covered with silver. I cannot forget the magic of this trip and sometimes go back to it to feel happy even now. Unfortunately, not everyone remembers it. In 2022 I asked Khalid and Shala about it and both could not remember it. However, Tariq Ahsan and Javed Athar did but they did not understand the charm and heightened emotion which I attach to it. For me, as I have just mentioned, it had a magic charm such as comes only rarely in life. There was also another mosque, the Iliasi mosque near Nawanshehr, to which I took my friends. We also took all our guests to this lovely mosque since there was a fountain in it and the water flowed right into it and collected in a pool outside. The water was clear and freezing cold and the sound of its flow and falling from one level to another gave it a captivating beauty which I enjoyed. However, though I appreciated all this, I never experienced the magic, the enchantment, the elevated mood, I experienced in that trip to the little mosque on the mountain above Kakul village. Once or twice, I persuaded the more adventurous among my friends—I believe Khalid, Abid, Javed and Tariq Ahsan—to accompany me to far- off Thandiani. We started in the morning and came back at dusk. The thick pine forest was so cool that we felt chilly in the summer. We ate voraciously and then started to climb down to PMA.

As I have mentioned before, I did not play any organized game ever in my life and, what is more, I actively disliked and discouraged such games and even persuaded my friends to give them up. I remember I called them battles in the guise of sports and joked that, instead of running after one ball, the players should be given a ball each. I also made fun of team spirit which always remained an unfelt emotion as far as I was concerned. Now that I have given this a thought, I have come to the conclusion that I probably hated the tension which competition and the team spirit created. Another reason could be that I might have a mild form of dyspraxia which was never diagnosed. I say this because I am exceptionally bad at catching or hitting a ball with either a bat, a racquet or a hockey stick. I am also pretty inept at parking and reversing cars. However, whereas one’s language skills are adversely affected by this condition, I was always above the average in reading, writing and speaking. Thus, maybe my self-diagnosis of dyspraxia is not correct after all. But, luckily for my self-esteem, this inability to play games did not bother me. It was not perceived as lack of something desirable by me. Instead, I was firmly convinced that the urge to play organized games was stupid and that I was quite rightly above it. Thus, I was self-righteous though miserable when my friends got the cricket bout or the football bug or something of the sort. I always thought it was weakness and silliness of some sort and mostly persuaded them to give up on these ‘silly’ pursuits of the ball and again take up the games and sports I myself enjoyed. I also never watched games or heard commentaries on the cricket matches which so mesmerized others. I too heard names like Kardar, Haneef and Imran Khan but I never watched them play nor did I have any interest in India-Pakistan matches. While my friends swooned about the performance of some player in cricket, I was indifferent and bored.

And what were the games I advocated to my friends? They were hide and seek and climbing trees. The hide and seek came into two versions. The first had a den in which one caught the captives i.e. players of the opposing team. I was very good at this game because I ran very fast and dared climb trees which others avoided. The second one, which I had invented was more bizarre and everybody called it ‘Torture’. If one was caught, they would have their hands twisted and head cuffed till they surrendered. Girls generally did not play this version of the game, but if they did, they were spared this ignoble treatment. But I did not hold everyone in my thrall as far as torture was concerned. Soon enough everybody rebelled against me and this game was abandoned.

(to be continued)