In one of its most laudable démarches, Pakistan honorifically opened doors to a very significant Sikh shrine, Gurudwara Kartarpur Sahib — that was awarded to Pakistan during the perfidiously executed Partition of British India in 1947. This is the first time in 72 years that the shrine will be accessible to the Sikh diaspora outside of Pakistan. Kartarpur is much revered by the Sikhs as this is where Baba Guru Nanak, the founding father of Sikhism, is believed to have spent the ultimate years of his life— preaching to the world about his philosophy of equality, oneness and truthfulness.

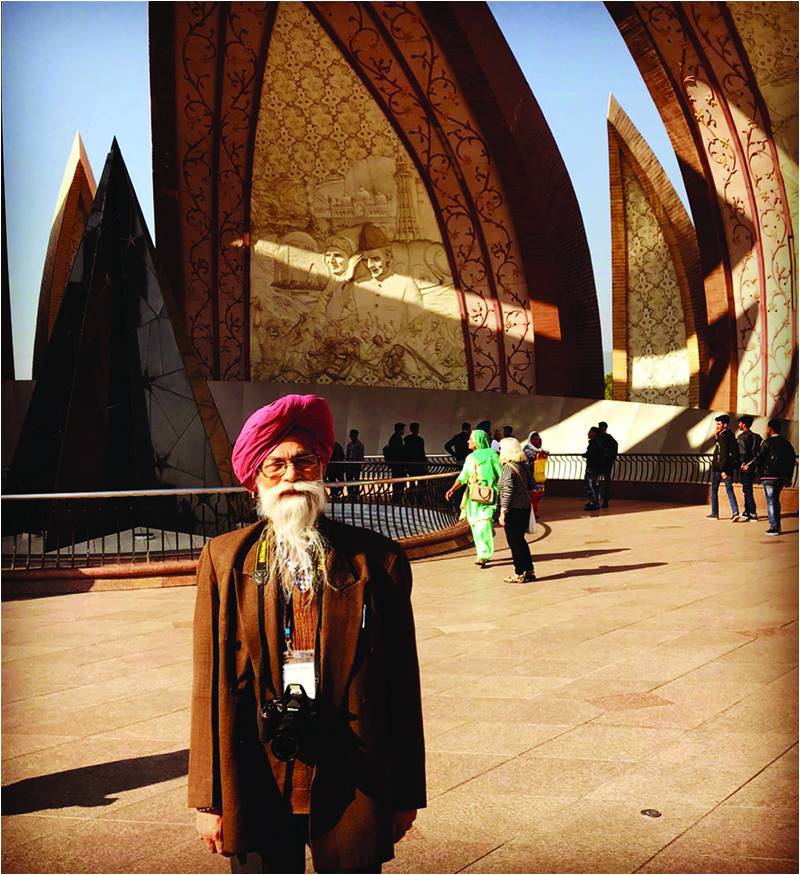

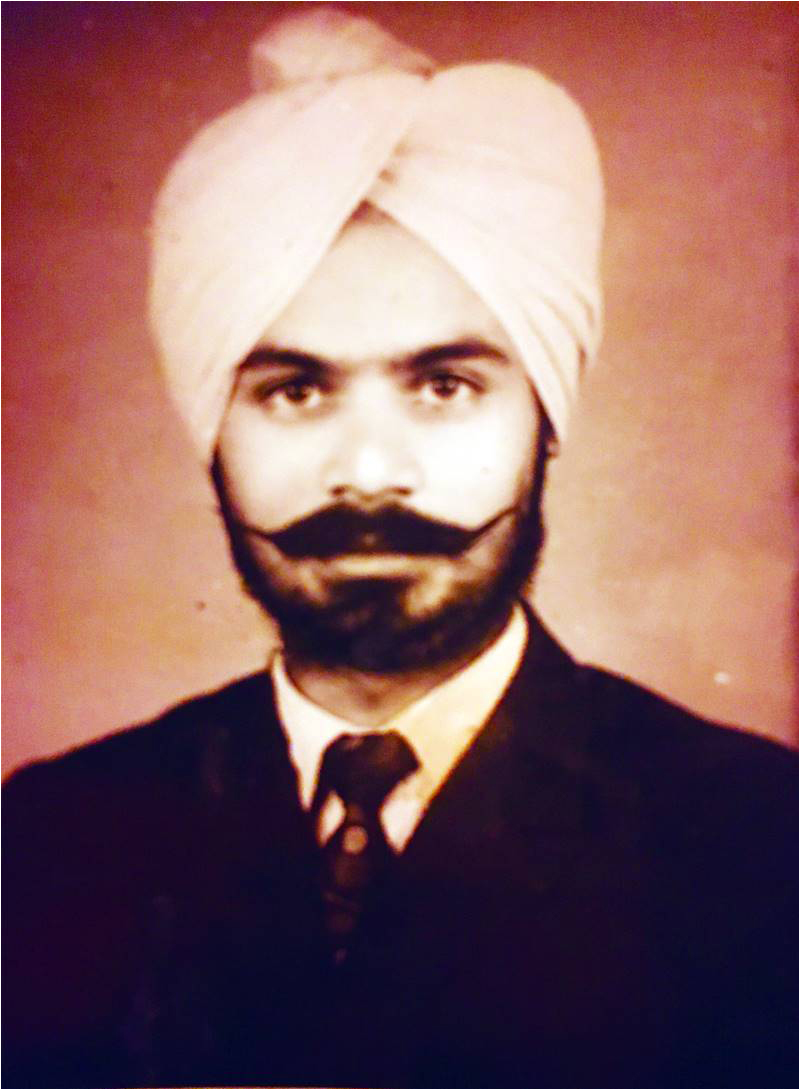

As thousands of Indian-Sikhs crossed the Indo-Pak border on the 9th of November, Onkar Singh was one of the hundreds who travelled overseas (from the US) to take part in the grand Sikh communion in Pakistan where the 550th birth anniversary of Baba Guru Nanak was being celebrated.

“As soon as I got out of the Islamabad airport, there was a huge crew of Pakistanis thronged outside the airport, enthusiastically beating drums. They welcomed us with garlands of flowers and affectionate hugs. I was so touched by their hospitality. What I felt at that moment is indescribable”, Mr. Singh reports, fondly looking back at his time in Pakistan from a month ago.

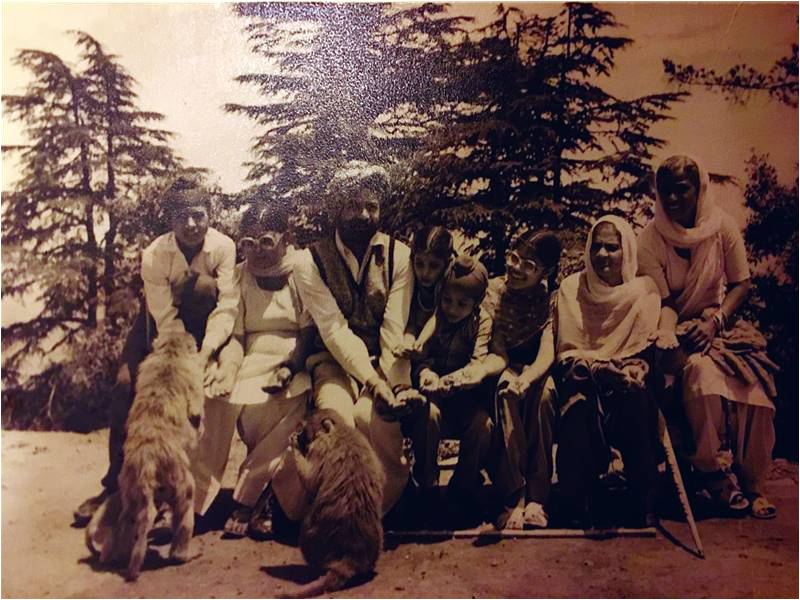

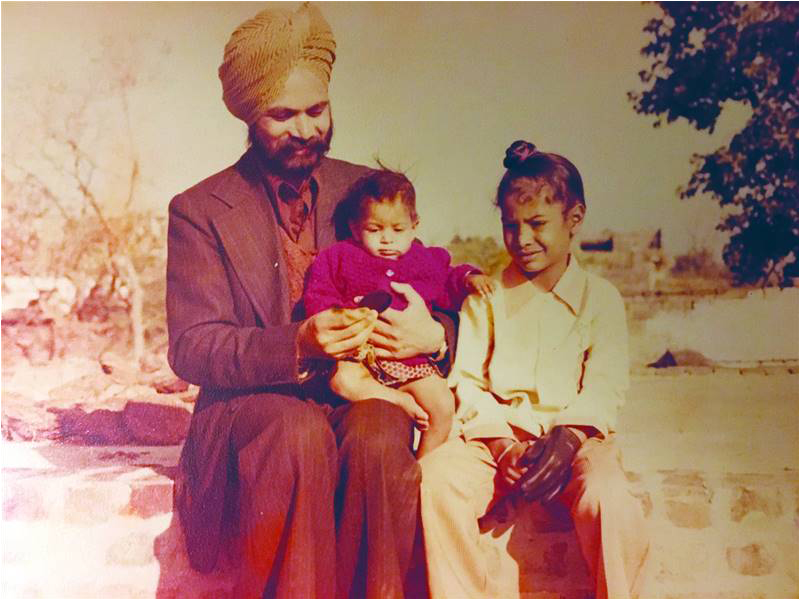

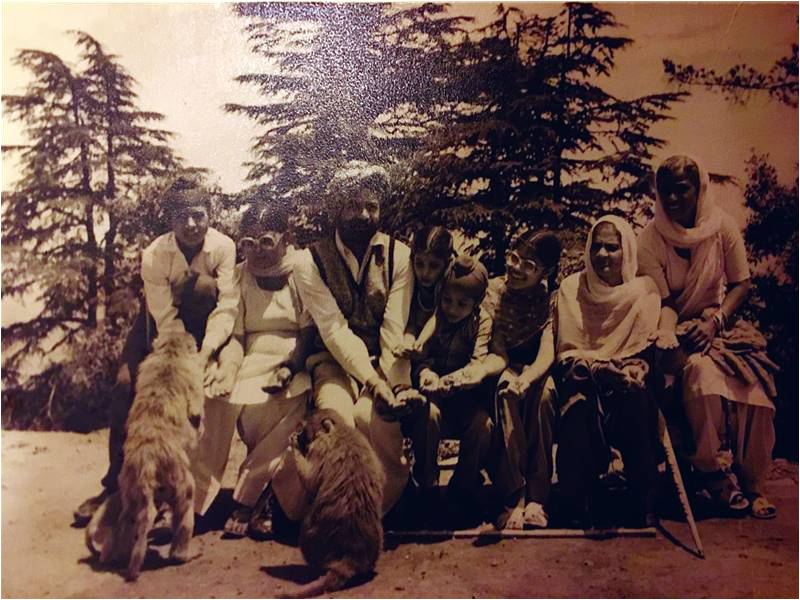

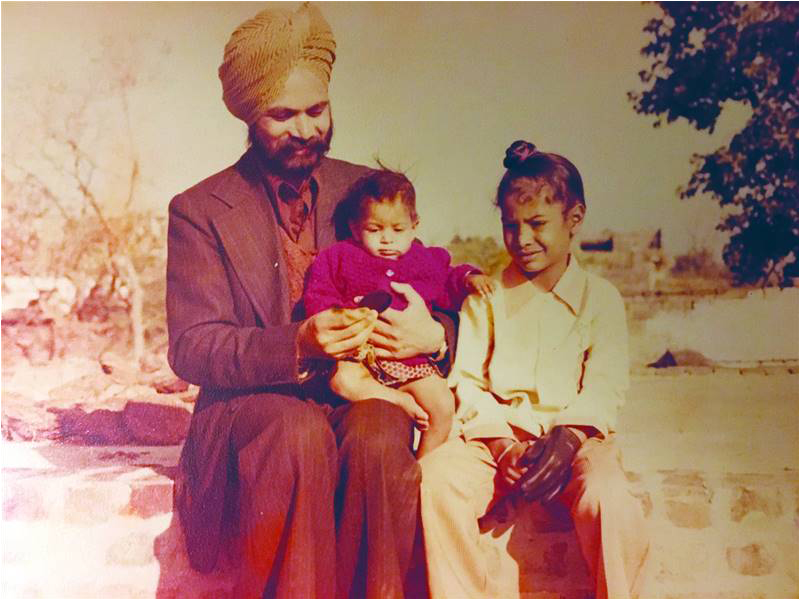

This was not the first time he was on that side of the “border” though. He spent a countable number of his summers in Lahore— before these religiously amorphous borders even existed. He was all of seven or eight years of age when the stark line of Partition was drawn —that divided not just people, but also languages and a shared culture. Teeming with a waft of joyous nostalgia, Onkar reminisces about the time (before the Raj grandiosely collapsed) he would often travel to Lahore from Kapurthala, East Punjab with his youngest sibling, and his Bibi (his mother) to meet his father; who would often take up menial tailoring jobs in Lahore.

“I do not remember much of my Lahori experience. But I remember the deafening whistles of the stationmaster at the Lahore railway station. I remember Bibi’s beautiful Phulkari suits; I remember listening to the most chaste Punjabi in Lahore; I remember looking at the most gorgeous Gori Mems.”

Although his septuagenarian memory is now fading, he faintly recalls Muslims being brutally ousted from their homes and Sikh or Hindu families settling in those spaces. “Many of them migrated to the US, Canada or live in the Queens’ land now” he shares and talks about the traumatic experience of his own migration to the US.

Circa 1960-70: it was the linguistic reorganization of India into different states that led to the abandonment of the Punjabi Suba. People were rendered jobless, militancy was at its peak, the green revolution degraded the soil and caused a lot of agrarian distress.

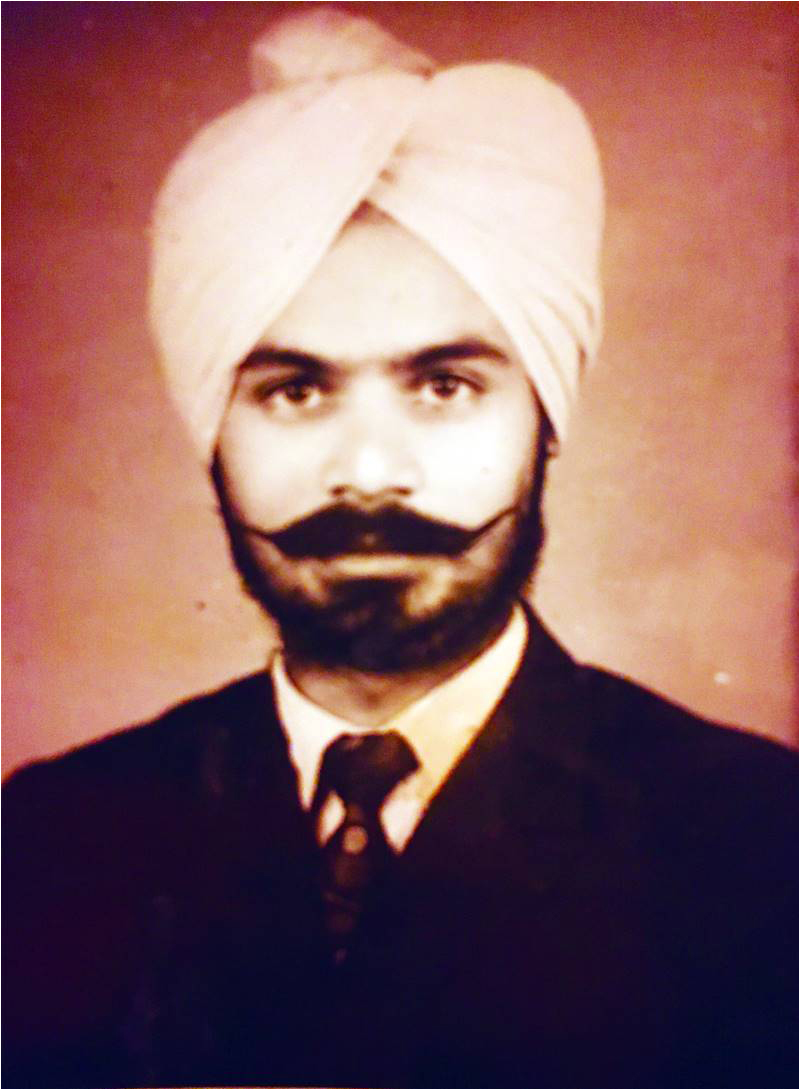

“I settled in Delhi in the early 1960s, married my wife, and was working with the Delhi Electricity Board, but could not redeem myself economically.”

In 1962, Onkar was briefly posted in Qadian, Gurdaspur, and vividly recalls being inside the premises of the site so closely associated with the Ahmadiyya community.

In the mid 1970s, he made his way to Zahedan, Iran, where he worked briefly as an electrical engineer. “There were some who called me a Shah sympathizer and asked me to go back to my country. Then the Shah was overthrown, Iran was dumped into a political tumult and I came back to India” he shares a poignant tale. Meanwhile, the fratricidal events under Indira Gandhi’s regime lead to her assassination and culminated into the marauding killing of the Sikhs in 1984 in New Delhi. At the outset of the 1984 rioting, Onkar Singh lost a child, as he lost a sense of belongingness to his mitti (soil). He migrated to the United States with pint-sized savings in his pocket, and rebuilt a whole new life from scratch.

Today, as he visits what he calls “fantastic pilgrim spots in Pakistan”, he still believes he’s visiting them in a reverie.

Citing a very endearing gesture by Pakistanis he tells, “Most passers-by would pull their cars over, roll their windows down and greet me. Sardaarji, welcome to Pakistan Ji, they’d say”.

“I was so humbled by the manner in which Pakistan and Pakistani people embraced me. Almost every time I went to a shop, the storekeepers would utter to me the most hospitable Sat Sri Akal (a Sikh religious greeting). When I went to Anarkali bazaar in Lahore, I did not have enough cash and the storekeeper refused to accept US dollars. I had just befriended Rizwan, a student from Oriental College Punjab University, who is pursuing a PhD in Sufism under the mentorship of Dr. Asma Qadri. I was at the bazaar with him; he quickly ran to the nearest ATM and came back with 30, 000 PKR cash. It took a lot of cajoling to have him take the money back”.

On the 10th of November as Mr. Singh was inside the premises of the Kartarpur Gurudwara, he genuflected in front of the Guru Granth Sahib with his eyes welling up with tears of divine joy. “During the Ardaas (supplication) that typically lasts about 5–6 minutes, I could not recite the hymns in unison with everyone else. I was so emotionally charged that I could not control my tears” he says.

Asking him about what his thoughts were on the construction of the Kartarpur Corridor and its management, he asserts that the the Auqaf board has done a praiseworthy job at preserving the Sikh shrines in Pakistan. He even visited Gurudwaras away from Lahore, deeper in the interiors that he claims were stunningly well-kept. Dismissing all the criticism being flung at the minimal $20 dollar fee being charged by every pilgrim, Onkar believes that since the facade of the Kartarpur Gurudwara has been expanded manifold, the Pakistani government needs a way to recollect the money that it spent.

“The 20$ service fee is jayaz (justifiable). After all, the Gurudwara compound has been expanded from 4 acres to an area of 42 acres. One also has to take into account the money that goes to pay off the salaries of people deployed to manage the Gurudwara— the immigration officers, the security, the drivers, the janitors, the administrative staff etc.” Onkar, shares his opinion.

Mr Singh, sums up this hopefully not “once in a lifetime” experience, as “Bohot Beautiful” (very beautiful). Now visiting his family in New Delhi, he desires to make another visit to Lahore before returning to New York —that has long been his been his abode, albeit never winning the title of being called “home”.

As thousands of Indian-Sikhs crossed the Indo-Pak border on the 9th of November, Onkar Singh was one of the hundreds who travelled overseas (from the US) to take part in the grand Sikh communion in Pakistan where the 550th birth anniversary of Baba Guru Nanak was being celebrated.

“As soon as I got out of the Islamabad airport, there was a huge crew of Pakistanis thronged outside the airport, enthusiastically beating drums. They welcomed us with garlands of flowers and affectionate hugs. I was so touched by their hospitality. What I felt at that moment is indescribable”, Mr. Singh reports, fondly looking back at his time in Pakistan from a month ago.

This was not the first time he was on that side of the “border” though. He spent a countable number of his summers in Lahore— before these religiously amorphous borders even existed. He was all of seven or eight years of age when the stark line of Partition was drawn —that divided not just people, but also languages and a shared culture. Teeming with a waft of joyous nostalgia, Onkar reminisces about the time (before the Raj grandiosely collapsed) he would often travel to Lahore from Kapurthala, East Punjab with his youngest sibling, and his Bibi (his mother) to meet his father; who would often take up menial tailoring jobs in Lahore.

“I do not remember much of my Lahori experience. But I remember the deafening whistles of the stationmaster at the Lahore railway station. I remember Bibi’s beautiful Phulkari suits; I remember listening to the most chaste Punjabi in Lahore; I remember looking at the most gorgeous Gori Mems.”

Although his septuagenarian memory is now fading, he faintly recalls Muslims being brutally ousted from their homes and Sikh or Hindu families settling in those spaces. “Many of them migrated to the US, Canada or live in the Queens’ land now” he shares and talks about the traumatic experience of his own migration to the US.

Circa 1960-70: it was the linguistic reorganization of India into different states that led to the abandonment of the Punjabi Suba. People were rendered jobless, militancy was at its peak, the green revolution degraded the soil and caused a lot of agrarian distress.

“I settled in Delhi in the early 1960s, married my wife, and was working with the Delhi Electricity Board, but could not redeem myself economically.”

In 1962, Onkar was briefly posted in Qadian, Gurdaspur, and vividly recalls being inside the premises of the site so closely associated with the Ahmadiyya community.

In the mid 1970s, he made his way to Zahedan, Iran, where he worked briefly as an electrical engineer. “There were some who called me a Shah sympathizer and asked me to go back to my country. Then the Shah was overthrown, Iran was dumped into a political tumult and I came back to India” he shares a poignant tale. Meanwhile, the fratricidal events under Indira Gandhi’s regime lead to her assassination and culminated into the marauding killing of the Sikhs in 1984 in New Delhi. At the outset of the 1984 rioting, Onkar Singh lost a child, as he lost a sense of belongingness to his mitti (soil). He migrated to the United States with pint-sized savings in his pocket, and rebuilt a whole new life from scratch.

Today, as he visits what he calls “fantastic pilgrim spots in Pakistan”, he still believes he’s visiting them in a reverie.

Citing a very endearing gesture by Pakistanis he tells, “Most passers-by would pull their cars over, roll their windows down and greet me. Sardaarji, welcome to Pakistan Ji, they’d say”.

“I was so humbled by the manner in which Pakistan and Pakistani people embraced me. Almost every time I went to a shop, the storekeepers would utter to me the most hospitable Sat Sri Akal (a Sikh religious greeting). When I went to Anarkali bazaar in Lahore, I did not have enough cash and the storekeeper refused to accept US dollars. I had just befriended Rizwan, a student from Oriental College Punjab University, who is pursuing a PhD in Sufism under the mentorship of Dr. Asma Qadri. I was at the bazaar with him; he quickly ran to the nearest ATM and came back with 30, 000 PKR cash. It took a lot of cajoling to have him take the money back”.

On the 10th of November as Mr. Singh was inside the premises of the Kartarpur Gurudwara, he genuflected in front of the Guru Granth Sahib with his eyes welling up with tears of divine joy. “During the Ardaas (supplication) that typically lasts about 5–6 minutes, I could not recite the hymns in unison with everyone else. I was so emotionally charged that I could not control my tears” he says.

Asking him about what his thoughts were on the construction of the Kartarpur Corridor and its management, he asserts that the the Auqaf board has done a praiseworthy job at preserving the Sikh shrines in Pakistan. He even visited Gurudwaras away from Lahore, deeper in the interiors that he claims were stunningly well-kept. Dismissing all the criticism being flung at the minimal $20 dollar fee being charged by every pilgrim, Onkar believes that since the facade of the Kartarpur Gurudwara has been expanded manifold, the Pakistani government needs a way to recollect the money that it spent.

“The 20$ service fee is jayaz (justifiable). After all, the Gurudwara compound has been expanded from 4 acres to an area of 42 acres. One also has to take into account the money that goes to pay off the salaries of people deployed to manage the Gurudwara— the immigration officers, the security, the drivers, the janitors, the administrative staff etc.” Onkar, shares his opinion.

Mr Singh, sums up this hopefully not “once in a lifetime” experience, as “Bohot Beautiful” (very beautiful). Now visiting his family in New Delhi, he desires to make another visit to Lahore before returning to New York —that has long been his been his abode, albeit never winning the title of being called “home”.