With crevices on brows and red flags hoisted aloft, university students appeared on the city squares of Pakistan to raise their concerns. Clad in red, they were chanting – nay singing – in rhythmic notes the chunks from poems of rebel poets whose poetry disseminates a message of revolution.

The posture of the students amazed many. Some called them socialists, while others termed them liberals.

Many ask whose agenda they are on – or whether they are truly ideologically motivated. Regardless, they have managed to resuscitate the debate on the political symbolism of the colour red.

But there is confusion as to what political beliefs these students are exhibiting – are they liberals, communists or socialists? Let us strive to clear the dust gathered around the thought being propounded.

To simplify, there is a need to clarify the terms like liberalism, communism and socialism.

Liberalism is a philosophy which promotes endeavours to remove obstacles – poverty, ignorance, disease and discrimination – that impede an individual’s will to live freely. In so doing, liberalism may remain within the ambit of a capitalist polity having a free competitive market.

Communism requires disbanding the capitalist structure which produces unevenness in society. In contrast, socialism is more flexible – it readily adjusts itself under a capitalist format. Thus, socialism does not necessarily endorse collision with capitalism. That is why a number of left-wing political parties in Pakistan have been nurturing a socialist agenda, speaking for the rights of the labouring class.

The seeds of socialism can be traced even before the Partition of the Subcontinent. The ideology sneaked into the region along with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. The Peshawar Conspiracy Cases that were pursued by the colonial regime between 1922 to 1927 and the Kanpur Bolshevik Case of May 1924 provide sufficient proof for the efforts of activists to resort to socialist and communist ideas in revolt against British imperialism.

After Pakistan came into being, the Pakistan Socialist Party (PSP) could not create ripples in the face of conservative parties which had just supported the creation of Pakistan on the basis of religion.

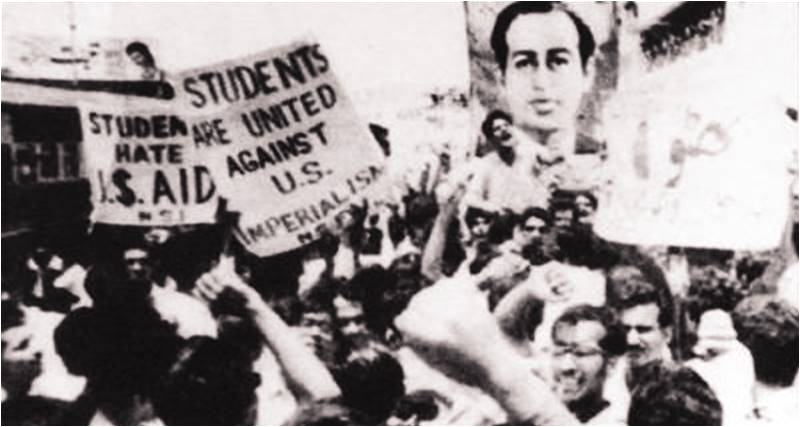

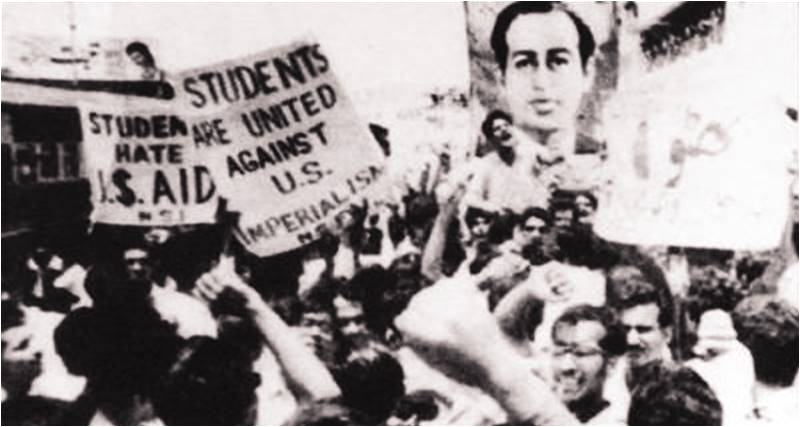

The Communist Party, in contrast, was able to win over the farmers and the labourers as it participated actively in labour strikes and language protests in early 1950s. In the wake of clashes between police and the Communist Party, Iskander Mirza imposed the first martial law on the 7th of October, 1958.

During the Ayub Khan era, the dissenting voices were considerably curbed. But following the Tashkent Declaration, the atmosphere in Pakistan turned antagonistic to President Ayub. Socialist elements again woke up from their snooze. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was shrewd enough to capture the direction of the veering winds, and thus he founded Pakistan Peoples Party whose manifesto, “Islam is our religion, democracy is our politics, socialism is our economy, power lies with the people”, was written by a Bengali communist, J.A. Rahim.

The PPP’s massive land reforms, nationalization campaign and efforts to abolish feudalism pleased the working class which joined the party in flocks.

Despite having similar ideologies, the PPP could not get close to the “Red Shirts” movement of Abdul Ghaffar Khan because of his looking at Pakistan through what was then seen as the prism of Afghanistan.

In General Zia-ul-Haq’s epoch, the left wing activists formed a “Struggle Group” to resist the repression of the military government. The group, soon, started publishing a magazine, Jaddojehad, which carried the revolutionary poems of Habib Jalib, Ahmad Faraz and Faiz Ahmad Faiz. In 1984, the poem, Main Baghi Hun written by Khalid Javed Jan became a symbol of struggle against the dictatorial reign of General Zia.

On the heels of 9/11 and Pakistan joining up as the front-line ally of the US, the socialist strain made its presence felt at the art and cultural platforms through theatres, peace conferences, songs and literature. Literary festivals at Karachi Arts Council and Alhamra Hall in Lahore apprised the people of the work of poets and writers who have spurred the masses for social reforms away from the shackles of right-wing politics.

The recent rise of students’ activities is not an outcome of some abrupt outpouring. It is, in fact, the continuation of a current of socialist thought that has been appearing in every political phase of Pakistan.

But where does the problem lie? Why does these students’ ideology not have acceptance in our society?

The answer is that there has always been the idea of socialism being anti-religion. People often underestimate the extent to which socialism can make adjustments with already existing frameworks.

Another reason for not having acceptability is the culture of free mixing of both genders in the students’ demonstrations. The optics of girls and boys shouting “revolution” being in proximity leads to outrage amongst many in Pakistan which still is dominated by conservative attitudes.

Last but not least, in rising for the rights of the working class, the current movement’s biggest error may be to get aligned – or be seen as getting aligned – with tendencies which are seen by the Powers That Be as “anti-state”. Lessons could be learned from the posture of the nascent PPP in the 1970s. It distanced itself from the National Awami Party’s perceived pro-Afghan maneuverings. Moreover, it raised the slogan of “Islamic Socialism” to create its acceptability in an otherwise orthodox society.

If these issues are properly dealt with, the current movement can make inroads in Pakistan’s social milieu. But it faces the danger of meeting the same fate as other such upsurges have experienced in the past.

The writer is an educationist and historian

The posture of the students amazed many. Some called them socialists, while others termed them liberals.

Many ask whose agenda they are on – or whether they are truly ideologically motivated. Regardless, they have managed to resuscitate the debate on the political symbolism of the colour red.

But there is confusion as to what political beliefs these students are exhibiting – are they liberals, communists or socialists? Let us strive to clear the dust gathered around the thought being propounded.

To simplify, there is a need to clarify the terms like liberalism, communism and socialism.

Liberalism is a philosophy which promotes endeavours to remove obstacles – poverty, ignorance, disease and discrimination – that impede an individual’s will to live freely. In so doing, liberalism may remain within the ambit of a capitalist polity having a free competitive market.

Communism requires disbanding the capitalist structure which produces unevenness in society. In contrast, socialism is more flexible – it readily adjusts itself under a capitalist format. Thus, socialism does not necessarily endorse collision with capitalism. That is why a number of left-wing political parties in Pakistan have been nurturing a socialist agenda, speaking for the rights of the labouring class.

The seeds of socialism can be traced even before the Partition of the Subcontinent. The ideology sneaked into the region along with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. The Peshawar Conspiracy Cases that were pursued by the colonial regime between 1922 to 1927 and the Kanpur Bolshevik Case of May 1924 provide sufficient proof for the efforts of activists to resort to socialist and communist ideas in revolt against British imperialism.

After Pakistan came into being, the Pakistan Socialist Party (PSP) could not create ripples in the face of conservative parties which had just supported the creation of Pakistan on the basis of religion.

The Communist Party, in contrast, was able to win over the farmers and the labourers as it participated actively in labour strikes and language protests in early 1950s. In the wake of clashes between police and the Communist Party, Iskander Mirza imposed the first martial law on the 7th of October, 1958.

During the Ayub Khan era, the dissenting voices were considerably curbed. But following the Tashkent Declaration, the atmosphere in Pakistan turned antagonistic to President Ayub. Socialist elements again woke up from their snooze. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was shrewd enough to capture the direction of the veering winds, and thus he founded Pakistan Peoples Party whose manifesto, “Islam is our religion, democracy is our politics, socialism is our economy, power lies with the people”, was written by a Bengali communist, J.A. Rahim.

The PPP’s massive land reforms, nationalization campaign and efforts to abolish feudalism pleased the working class which joined the party in flocks.

Despite having similar ideologies, the PPP could not get close to the “Red Shirts” movement of Abdul Ghaffar Khan because of his looking at Pakistan through what was then seen as the prism of Afghanistan.

In General Zia-ul-Haq’s epoch, the left wing activists formed a “Struggle Group” to resist the repression of the military government. The group, soon, started publishing a magazine, Jaddojehad, which carried the revolutionary poems of Habib Jalib, Ahmad Faraz and Faiz Ahmad Faiz. In 1984, the poem, Main Baghi Hun written by Khalid Javed Jan became a symbol of struggle against the dictatorial reign of General Zia.

On the heels of 9/11 and Pakistan joining up as the front-line ally of the US, the socialist strain made its presence felt at the art and cultural platforms through theatres, peace conferences, songs and literature. Literary festivals at Karachi Arts Council and Alhamra Hall in Lahore apprised the people of the work of poets and writers who have spurred the masses for social reforms away from the shackles of right-wing politics.

The recent rise of students’ activities is not an outcome of some abrupt outpouring. It is, in fact, the continuation of a current of socialist thought that has been appearing in every political phase of Pakistan.

But where does the problem lie? Why does these students’ ideology not have acceptance in our society?

The answer is that there has always been the idea of socialism being anti-religion. People often underestimate the extent to which socialism can make adjustments with already existing frameworks.

Another reason for not having acceptability is the culture of free mixing of both genders in the students’ demonstrations. The optics of girls and boys shouting “revolution” being in proximity leads to outrage amongst many in Pakistan which still is dominated by conservative attitudes.

Last but not least, in rising for the rights of the working class, the current movement’s biggest error may be to get aligned – or be seen as getting aligned – with tendencies which are seen by the Powers That Be as “anti-state”. Lessons could be learned from the posture of the nascent PPP in the 1970s. It distanced itself from the National Awami Party’s perceived pro-Afghan maneuverings. Moreover, it raised the slogan of “Islamic Socialism” to create its acceptability in an otherwise orthodox society.

If these issues are properly dealt with, the current movement can make inroads in Pakistan’s social milieu. But it faces the danger of meeting the same fate as other such upsurges have experienced in the past.

The writer is an educationist and historian