The conclusion of COP28 in Dubai marks a critical moment in the ongoing fight against climate change. In the aftermath of COP28, two contrasting narratives emerged: one celebrates significant progress and calls for collective action, while the other is clouded by disappointment and a conflict of interest.

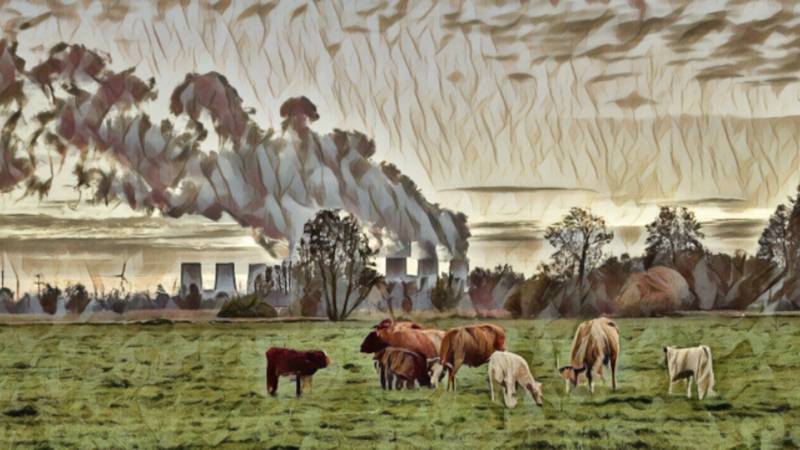

The clash between fossil fuel proponents and decarbonisation advocates highlights a clear conflict of interests, raising concerns about their ability to effectively address the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions. To reach the goal of keeping global warming within 1.5°C, rapid decarbonisation is essential, which necessitates a swift transition to clean energy form both the demand and supply sides. However, the influence of carbon culprits on climate policies may hinder this transition.

Throughout the course of history, the clash between scientific advancements and vested interests has been a symbol of societal discord. Visionaries like Copernicus and Galileo, who brought forth groundbreaking scientific discoveries, faced opposition and criticism from followers of religious doctrines. In today's world, the urgent warnings raised by climate science are met with denial and resistance from those driven by financial gain and influence.

The struggles faced by Copernicus and Galileo echo in the challenges faced by present-day climate activists. The fossil fuel industry, akin to outdated beliefs, assumes the role of the 'Carbon Culprit,' wielding power and greed that endanger our planet. Despite being aware of the catastrophic consequences, they persist in prioritising personal profit over the well-being of our global home. This unwavering pursuit of financial gain puts the future of planet at risk, particularly endangering vulnerable communities already grappling with the impacts of climate change.

Carbon culprits are unlikely to advocate against their own self-interests, further complicating the situation

Reflect on this harsh truth: the actions of a small group of carbon emitters impact the vast majority of the world's population. This irony becomes clear when we consider that it has taken almost 30 years to acknowledge the significance of carbon emissions, especially in relation to fossil fuels within the COP agenda. This extended journey towards recognising this fundamental fact raises the question: how much longer will it take for us to break free from our dependence on fossil fuels? Are we facing another couple of centuries or even more? Given the current pace, achieving the ambitious goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 seems daunting, casting doubt on our collective ability to effectively address this urgent global crisis.

The COP28 agreement's call for a "transition away" from fossil fuels contains troubling contradictions. Its vague language offers nations room to prolong coal, oil, and gas use while claiming compliance. This ambiguity allows fossil fuel advocates to appear as climate allies while maintaining the status quo.

Celebrations by figures like Al Jaber highlight the deep-seated issue of greenwashing in climate politics. This misleading narrative masks reality, enabling fossil fuel interests to manipulate discourse. The text's ambiguity, including transitional fuels like methane gas, paradoxically escalates greenhouse gas emissions, hindering net-zero goals. It underscores the challenge in deciphering climate politics, urging a critical view to distinguish genuine action from industry manipulation. This disparity between rhetoric and action demands clarity and concrete steps to genuinely transition away from fossil fuels.

The financial commitments stood at a mere $85 billion, a notably modest sum given the enormity of the climate crisis. To contextualise, a single company's staggering $150 billion investment aimed at escalating greenhouse gas production vastly overshadowed the funds dedicated to combating climate change

It is indeed a perplexing challenge to address the issue of climate policies when carbon profiteers play a significant role. The conflicting interests of these different groups make it difficult to find a common ground. Unfortunately, decision-making within influential circles tends to favour those who are already in power, which only adds to the problem. What makes it even more disheartening is the fact that carbon culprits are unlikely to advocate against their own self-interests, further complicating the situation.

Dr Sultan Al Jabar, the president of COP28 and a prominent figure in climate discussions, has brought forth a glaring contradiction. Despite his role as the chief executive of ADNOC, the national oil and gas company of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Al Jabar has expressed scepticism regarding the scientific foundation behind the push for a fossil fuel phase-out. Paradoxically, he, at the eve of COP28, has also unveiled plans of a substantial $150 billion investment in oil and gas aiming to sustain current production levels. This contradiction raises significant concern and starkly highlights the disparity between climate policy rhetoric and actual actions taken.

The COP 28 Presidency aimed to accelerate a just transition to clean energy, address climate finance challenges, prioritise people's well-being, and ensure inclusivity across initiatives. However, the financial commitments stood at a mere $85 billion, a notably modest sum given the enormity of the climate crisis. To contextualise, a single company's staggering $150 billion investment aimed at escalating greenhouse gas production vastly overshadowed the funds dedicated to combating climate change. Furthermore, the USA's expenditure of approximately $20 trillion from 2001 to 2023 on various regional wars significantly contributed to increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite this, a detailed examination of the financial allocations revealed during COP28 unveiled five distinct financial channels aimed at tackling the challenges posed by climate change. These channels encompassed commitments like the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) amounting to $792 million, the Adaptation Fund (AF) with $134 million, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) with $129 million, and the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) pledging $31 million, resulting in a total pledge of $1,086 million. Additionally, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) emerged as the largest contributor, pledging a substantial $3.5 billion. However, the remaining funds were directed towards areas such as Energy, Finance, Lives and Livelihoods, and Inclusion.

In the wake of COP28, amidst the maze of contradictions and challenges, a glimmer of opportunity emerges. While the conference outcomes reveal the daunting gap between ambition and action, they also spotlight the urgent need for resolute and transparent measures. The establishment of financial channels, though modest in scale, signals a step toward addressing climate change. However, the need for transformative action remains paramount. This pivotal moment calls for unwavering dedication, collaborative efforts, and a recalibration of priorities among nations and stakeholders. Climate activists, vital watchdogs of progress and accountability, must closely monitor pledged commitments and corresponding actions.

Relying on carbon culprits, who primarily safeguard their interests, is insufficient. Instead, every climate activist must play a proactive role, fostering a culture of collective responsibility and driving authentic change toward a thriving, sustainable planet.