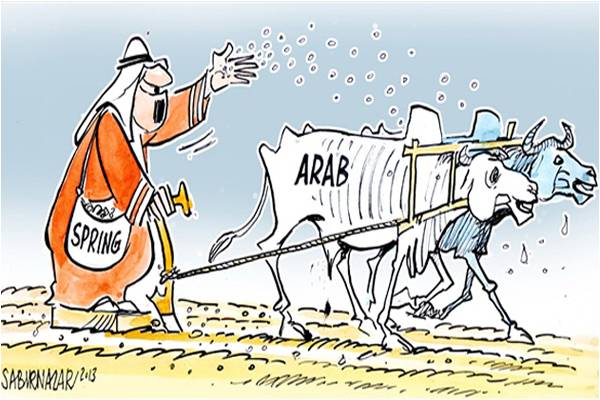

Dr Tahirul Qadri has revived the imagination of the media with talk of a “revolution”. He has triggered panic in the ruling party and government and provoked it to take desperate measures to deal with him. As a consequence, the perennial anti-democracy conspirators have crept out of the woodwork to predict that the end is nigh for the Nawaz Sharif regime. Is this assessment correct?

Dr Qadri is a religio-political maverick with a significant and dedicated following in Pakistan and abroad, thanks to his Grand Fatwa against “radical Islam” that is waging war with the West and its allies. Since his Minhaj ul Quran (MuQ) project took off in the 1990s, he has been trying to carve out a political career for himself in Pakistan by all manner of gimmicks and antics. But his scattered supporters have never been able to harness their excellent organisational skills for electoral purposes in Pakistan’s first-past-the-post system. Consequently, Dr Qadri has made several forays into Pakistan from self-imposed exile in Canada in the last decade and tried to whip up public and institutional support for his unbridled ambitions. Unfortunately, the established parties — religious, ethnic and liberal-centralist — will have no truck with a demagogue like him. Indeed, when his attempt to woo the Supreme Court in 2013 to remove the corrupt PPP government and postpone the elections backfired, he blasted the courts and high-tailed it back to Canada. Now, egged on by pro-military political orphans like the Chaudhries of Gujrat and Sheikh Rashid, he has returned to Pakistan in the expectation that perhaps the military, that is at odds with the Sharif regime for various reasons, will adopt him as its front-man to “save Pakistan” by dethroning the Sharifs.

Dr Qadri’s political histrionics have catapulted him to the top of media headlines. The Sharif government’s panicky response in Lahore, where police reaction led to the deaths of a dozen MuQ activists, and Islamabad, where an international flight bringing Dr Qadri to Pakistan was stupidly diverted to Lahore, have helped to make him temporarily as “the most dangerous threat” to the Sharif regime and added grist to the rumour mills predicting doom for it.

There is no doubt that the military leadership is unhappy, even angry, with Nawaz Sharif for not letting General Musharraf off the hook, siding with GEO instead of the ISI and dragging his feet on launching military operations against the Taliban in North Waziristan — in short, for challenging its historical monopoly on defining and exercising power on critical “national security” issues. But it would be misplaced concreteness to read this as a sign that the military is conspiring to seize power directly or even to install a long-term handpicked caretaker government. The military’s doctrine of “soft power” is aimed at cutting elected civilian regimes down to size and pulling strings behind the scenes, as it did during the Zardari years, rather than ruling directly in the face of the myriad problems that beset Pakistan.

This doctrine is based on a realistic assessment of the ground realities. First, the long-term existential war against terrorism and a separatist insurgency requires a national political consensus comprising political parties, state institutions and the media, which only an elected dispensation can deliver, however imperfectly. This objective neither Dr Qadri nor Imran Khan can deliver alone or collectively so long as the PMLN, PPP, judiciary and independent media remain outside the tent. Second, the economy requires tough and unpopular decisions that the military is loath to take. Third, Imran Khan’s reluctance to join forces with Dr Qadri is born of his refusal to play second fiddle. While Imran is certainly interested in hastening the demise of the Sharif regime followed by fresh elections, he is unlikely to support any extra-constitutional back-door entry along with the likes of Dr Qadri on the back of the military. Fourth, General Raheel Sharif’s soldierly temperament suggests that he is not about to let the ISI run GHQ as in the recent past. He would much rather use the ISI to get a freer hand to deal with national security issues vis a vis the elected government than conspire to seize power directly or enable unpredictable power-hungry people like Dr Qadri or Imran Khan to wield it on the military’s behalf. Indeed, he is also likely to be more focused on easing out the Kayani team in GHQ and ISI that he has inherited and replace it with his handpicked new one in consolidating his power base within the military and between the military and civilians.

However, the situation will remain precipitous for some time to come, with Dr Qadri and Imran Khan hogging the headlines and shaking up the government through demonstrations and marches. In the final analysis, however, it is General Raheel Sharif who will call the shots. And he is not about to wrap up the Sharifs despite the ongoing tension in civil-military relations.

Dr Qadri is a religio-political maverick with a significant and dedicated following in Pakistan and abroad, thanks to his Grand Fatwa against “radical Islam” that is waging war with the West and its allies. Since his Minhaj ul Quran (MuQ) project took off in the 1990s, he has been trying to carve out a political career for himself in Pakistan by all manner of gimmicks and antics. But his scattered supporters have never been able to harness their excellent organisational skills for electoral purposes in Pakistan’s first-past-the-post system. Consequently, Dr Qadri has made several forays into Pakistan from self-imposed exile in Canada in the last decade and tried to whip up public and institutional support for his unbridled ambitions. Unfortunately, the established parties — religious, ethnic and liberal-centralist — will have no truck with a demagogue like him. Indeed, when his attempt to woo the Supreme Court in 2013 to remove the corrupt PPP government and postpone the elections backfired, he blasted the courts and high-tailed it back to Canada. Now, egged on by pro-military political orphans like the Chaudhries of Gujrat and Sheikh Rashid, he has returned to Pakistan in the expectation that perhaps the military, that is at odds with the Sharif regime for various reasons, will adopt him as its front-man to “save Pakistan” by dethroning the Sharifs.

Dr Qadri’s political histrionics have catapulted him to the top of media headlines. The Sharif government’s panicky response in Lahore, where police reaction led to the deaths of a dozen MuQ activists, and Islamabad, where an international flight bringing Dr Qadri to Pakistan was stupidly diverted to Lahore, have helped to make him temporarily as “the most dangerous threat” to the Sharif regime and added grist to the rumour mills predicting doom for it.

There is no doubt that the military leadership is unhappy, even angry, with Nawaz Sharif for not letting General Musharraf off the hook, siding with GEO instead of the ISI and dragging his feet on launching military operations against the Taliban in North Waziristan — in short, for challenging its historical monopoly on defining and exercising power on critical “national security” issues. But it would be misplaced concreteness to read this as a sign that the military is conspiring to seize power directly or even to install a long-term handpicked caretaker government. The military’s doctrine of “soft power” is aimed at cutting elected civilian regimes down to size and pulling strings behind the scenes, as it did during the Zardari years, rather than ruling directly in the face of the myriad problems that beset Pakistan.

This doctrine is based on a realistic assessment of the ground realities. First, the long-term existential war against terrorism and a separatist insurgency requires a national political consensus comprising political parties, state institutions and the media, which only an elected dispensation can deliver, however imperfectly. This objective neither Dr Qadri nor Imran Khan can deliver alone or collectively so long as the PMLN, PPP, judiciary and independent media remain outside the tent. Second, the economy requires tough and unpopular decisions that the military is loath to take. Third, Imran Khan’s reluctance to join forces with Dr Qadri is born of his refusal to play second fiddle. While Imran is certainly interested in hastening the demise of the Sharif regime followed by fresh elections, he is unlikely to support any extra-constitutional back-door entry along with the likes of Dr Qadri on the back of the military. Fourth, General Raheel Sharif’s soldierly temperament suggests that he is not about to let the ISI run GHQ as in the recent past. He would much rather use the ISI to get a freer hand to deal with national security issues vis a vis the elected government than conspire to seize power directly or enable unpredictable power-hungry people like Dr Qadri or Imran Khan to wield it on the military’s behalf. Indeed, he is also likely to be more focused on easing out the Kayani team in GHQ and ISI that he has inherited and replace it with his handpicked new one in consolidating his power base within the military and between the military and civilians.

However, the situation will remain precipitous for some time to come, with Dr Qadri and Imran Khan hogging the headlines and shaking up the government through demonstrations and marches. In the final analysis, however, it is General Raheel Sharif who will call the shots. And he is not about to wrap up the Sharifs despite the ongoing tension in civil-military relations.