I have been learning about transitions these days. Change is constant and completely to be expected but even as mature adults, change can be overwhelming and even paralysing.

This year, we have more change than most in our family – a high school graduate, an international relocation and so much more. In the face of all of this, my first instinct is to lie in bed until it is all over. Clearly that is not an option but it has made me reflect on how can one equip oneself to embrace change and benefit from it?

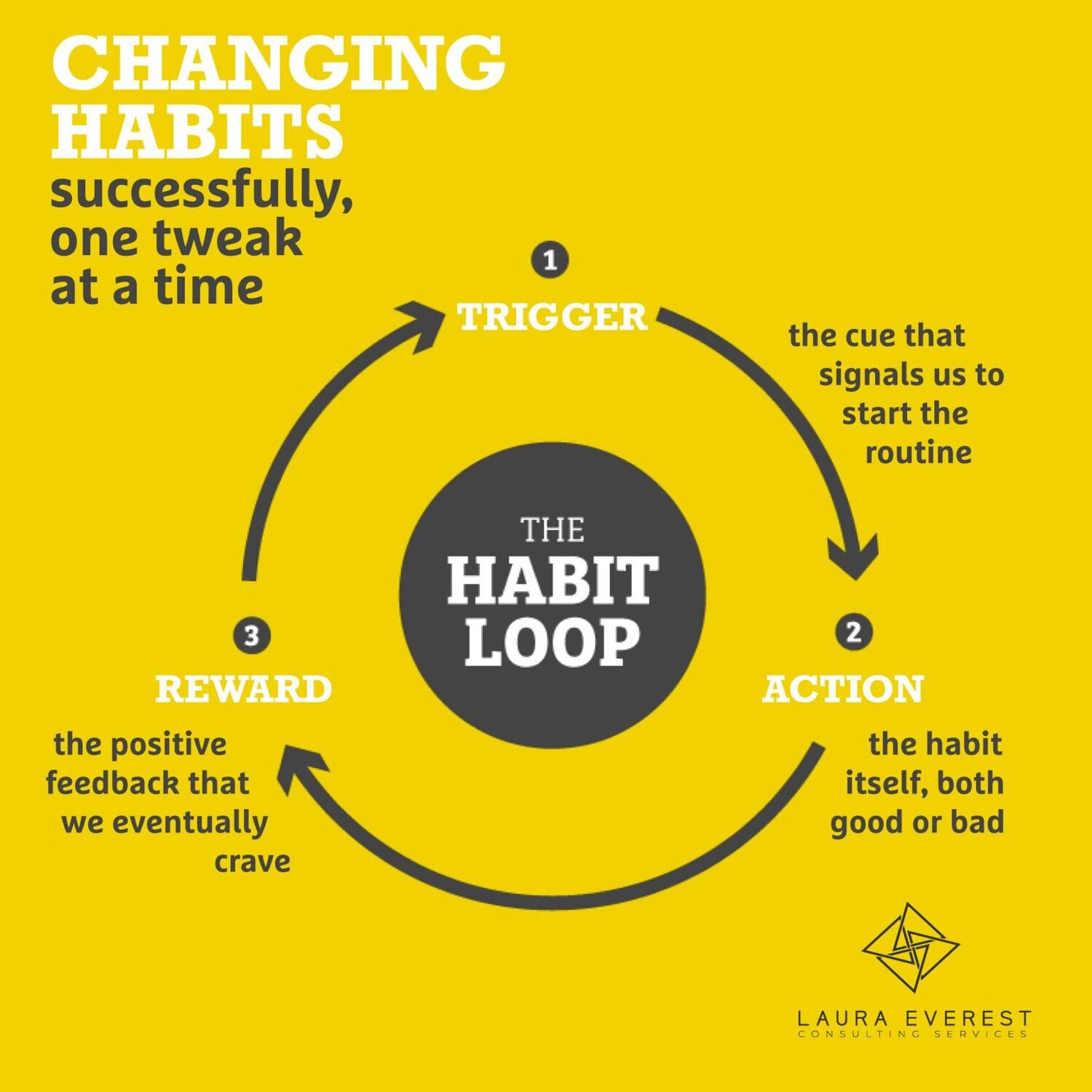

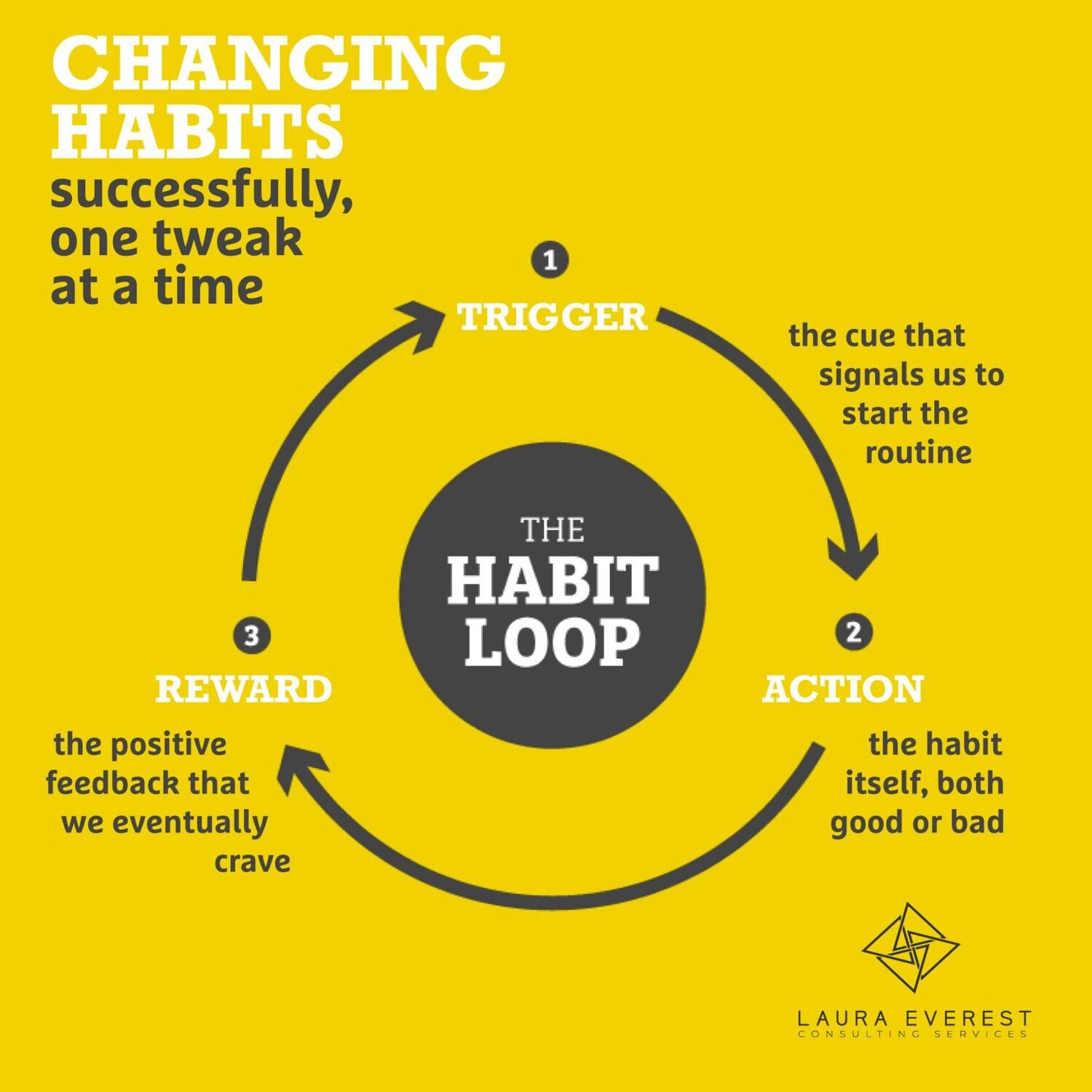

There is now a growing amount of literature on habits and routines which makes for fascinating analysis in managing change. As human beings, we are prone to habits which develop into routines, and then routines fill up our days. As Anne Dillard said in her wonderful book The Writing Life, how we spend our days is how we spend our lives.

James Clear, a leading expert on habit formation and author of international best seller Atomic Habits studied neuroscience, psychology and biological instincts to draw conclusions about good and bad habits.

We all know them: days that start off well with exercise, some quiet time and perhaps some form of spiritual or meditative practice are better than those when your alarm fails to ring and you get out of bed groggy and miserable.

Clear’s thesis is simple: we rise to the levels of our goals by the systems we create. By creating new systems designed to succeed, we can rise to the top of our fields. Even 1 percent consistently a day is better than nothing every day. A case in point is where a woman decided to read all of Shakespeare’s works in a year. It took her 20 minutes a day. Breaking down every target into attainable elements allows one to transform one’s habits and lead to achievement of one’s aims.

Small manageable habits allow you to fulfill your potential, be it becoming an athlete, building a business, writing a story, or being able to study for exams.

Human behavior may change over time but the essentials of human behavior do not. Our ancestors also felt love, fear, anxiety and anger. Our nervous systems are built around that - the flight or fear response, happiness when one is doing things for others, endorphins when we move our bodies, and so on.

We learn from others. In my home, my parents had very different habits. My father woke at 5 am and took two hours of quiet time to walk, read, write and reflect. He managed his life with clock work efficiency, which allowed him to write over 24 books in addition to sustaining a professional career and being a hands-on parent. My mother would rise later but stay up late into the night spending time with family, friends and work. She found her creativity after the family was asleep and ended up translating and abridging 12 volumes of Persian folklore into a single tome – having spent a decade working on it incrementally every day.

They modelled themselves into a sequential sort of relationship, following their individual habits and routines – each reflecting their goals of health, productivity and relationships. One or the other of them was almost always awake around the clock which served us well as a family of night owls and early rising fowl.

They modelled themselves into a sequential sort of relationship, following their individual habits and routines – each reflecting their goals of health, productivity and relationships. One or the other of them was almost always awake around the clock which served us well as a family of night owls and early rising fowl.

At work, I am surrounded by those who wake up at 5 am and run 5 miles, cycle to work or meditate before coming to the office. This means they are usually much calmer and in control of their day, compared to those who roll out of bed late, are habitually late to meetings, and spend the rest of the day catching up like a headless chicken. It is great fun to observe the two camps especially if you play in both.

It is hard to achieve change. Too often, we convince ourselves that defining moments require massive action, whether cramming for an exam, losing weight through quick fix diets, working on a paper overnight before the deadline. That it can only be done by making a palpable change which others will notice. It is far harder to put into practice a daily routine which is incremental where results are not noticeable immediately.

The logic applies widely – one scoffs at the idea of reducing calorie intake by 200 calories a day, but over seven days that compounds to an additional 1400 calories. That applies equally to learning a language, walking so much further, or being able to save a little more money.

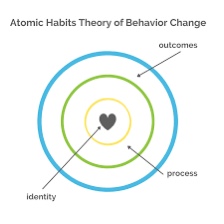

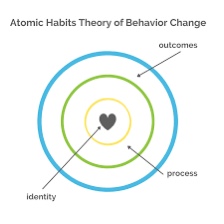

Intrinsic motivation plays a role. In leadership exercises, one is often taught to identify who you want to become, what characteristics you observe in any leader, and how to become one yourself. President Barack Obama, for instance, was known for his rational pragmatism as well as commitment to daily practices of exercise and reading; President Donald Trump for his direct and effective messaging and time at the golf course, the queen of television Oprah Winfrey for her ability to connect with her audiences. They were not born with these skills. They honed them over time. Your goals therefore shape your identity. Becoming a reader or reading twenty minutes a day allows you to read a book, walking twenty minutes a day allows you to become a walker, and practicing piano allows you to become a musician. This allows us to become who we say we want to be – and can also impact our ability to change – whether to be better at waking up in the mornings, being good with technology or even simply being early or late.

At the local gym, my trainer revealed how it is always the same people who are consistently late or early, not because of traffic or the weather patterns but there are those for whom time has value.

If identity is tied up with our thoughts and actions, whether at an individual, team or societal level, habits can be too. Think for a moment about the difference between the value of time between Japan and closer to home in Pakistan.

What habits do we cultivate or pay homage to? Identity itself is fascinating in its linguistic roots – coming from Latin root of essentitas or being and identidem – essentially that our identity is our repeated beingness. In real life that means, the process of building habits means that we become who we are.

This is a lesson I feel like I am learning late in life. I wish someone had sat me down in early adulthood to explain these truths. But, as I have discovered, it is never too late as no single instance is not the definition of the whole of our life.

In the end, as the author James Clear articulates, habits are not about having something or the external validation of what may come from better habits. They are the channels through and through which you develop yourself – you become your habits.

In my case, it is about navigating change and transition with presence and grace rather than trepidation and fear. In your case, it may be vastly different but I certainly hope that these habits work for you rather than against you.

This year, we have more change than most in our family – a high school graduate, an international relocation and so much more. In the face of all of this, my first instinct is to lie in bed until it is all over. Clearly that is not an option but it has made me reflect on how can one equip oneself to embrace change and benefit from it?

There is now a growing amount of literature on habits and routines which makes for fascinating analysis in managing change. As human beings, we are prone to habits which develop into routines, and then routines fill up our days. As Anne Dillard said in her wonderful book The Writing Life, how we spend our days is how we spend our lives.

James Clear, a leading expert on habit formation and author of international best seller Atomic Habits studied neuroscience, psychology and biological instincts to draw conclusions about good and bad habits.

We all know them: days that start off well with exercise, some quiet time and perhaps some form of spiritual or meditative practice are better than those when your alarm fails to ring and you get out of bed groggy and miserable.

Clear’s thesis is simple: we rise to the levels of our goals by the systems we create. By creating new systems designed to succeed, we can rise to the top of our fields. Even 1 percent consistently a day is better than nothing every day. A case in point is where a woman decided to read all of Shakespeare’s works in a year. It took her 20 minutes a day. Breaking down every target into attainable elements allows one to transform one’s habits and lead to achievement of one’s aims.

Small manageable habits allow you to fulfill your potential, be it becoming an athlete, building a business, writing a story, or being able to study for exams.

Human behavior may change over time but the essentials of human behavior do not. Our ancestors also felt love, fear, anxiety and anger. Our nervous systems are built around that - the flight or fear response, happiness when one is doing things for others, endorphins when we move our bodies, and so on.

We learn from others. In my home, my parents had very different habits. My father woke at 5 am and took two hours of quiet time to walk, read, write and reflect. He managed his life with clock work efficiency, which allowed him to write over 24 books in addition to sustaining a professional career and being a hands-on parent. My mother would rise later but stay up late into the night spending time with family, friends and work. She found her creativity after the family was asleep and ended up translating and abridging 12 volumes of Persian folklore into a single tome – having spent a decade working on it incrementally every day.

They modelled themselves into a sequential sort of relationship, following their individual habits and routines – each reflecting their goals of health, productivity and relationships. One or the other of them was almost always awake around the clock which served us well as a family of night owls and early rising fowl.

They modelled themselves into a sequential sort of relationship, following their individual habits and routines – each reflecting their goals of health, productivity and relationships. One or the other of them was almost always awake around the clock which served us well as a family of night owls and early rising fowl.At work, I am surrounded by those who wake up at 5 am and run 5 miles, cycle to work or meditate before coming to the office. This means they are usually much calmer and in control of their day, compared to those who roll out of bed late, are habitually late to meetings, and spend the rest of the day catching up like a headless chicken. It is great fun to observe the two camps especially if you play in both.

It is hard to achieve change. Too often, we convince ourselves that defining moments require massive action, whether cramming for an exam, losing weight through quick fix diets, working on a paper overnight before the deadline. That it can only be done by making a palpable change which others will notice. It is far harder to put into practice a daily routine which is incremental where results are not noticeable immediately.

The logic applies widely – one scoffs at the idea of reducing calorie intake by 200 calories a day, but over seven days that compounds to an additional 1400 calories. That applies equally to learning a language, walking so much further, or being able to save a little more money.

Intrinsic motivation plays a role. In leadership exercises, one is often taught to identify who you want to become, what characteristics you observe in any leader, and how to become one yourself. President Barack Obama, for instance, was known for his rational pragmatism as well as commitment to daily practices of exercise and reading; President Donald Trump for his direct and effective messaging and time at the golf course, the queen of television Oprah Winfrey for her ability to connect with her audiences. They were not born with these skills. They honed them over time. Your goals therefore shape your identity. Becoming a reader or reading twenty minutes a day allows you to read a book, walking twenty minutes a day allows you to become a walker, and practicing piano allows you to become a musician. This allows us to become who we say we want to be – and can also impact our ability to change – whether to be better at waking up in the mornings, being good with technology or even simply being early or late.

At the local gym, my trainer revealed how it is always the same people who are consistently late or early, not because of traffic or the weather patterns but there are those for whom time has value.

If identity is tied up with our thoughts and actions, whether at an individual, team or societal level, habits can be too. Think for a moment about the difference between the value of time between Japan and closer to home in Pakistan.

What habits do we cultivate or pay homage to? Identity itself is fascinating in its linguistic roots – coming from Latin root of essentitas or being and identidem – essentially that our identity is our repeated beingness. In real life that means, the process of building habits means that we become who we are.

This is a lesson I feel like I am learning late in life. I wish someone had sat me down in early adulthood to explain these truths. But, as I have discovered, it is never too late as no single instance is not the definition of the whole of our life.

In the end, as the author James Clear articulates, habits are not about having something or the external validation of what may come from better habits. They are the channels through and through which you develop yourself – you become your habits.

In my case, it is about navigating change and transition with presence and grace rather than trepidation and fear. In your case, it may be vastly different but I certainly hope that these habits work for you rather than against you.