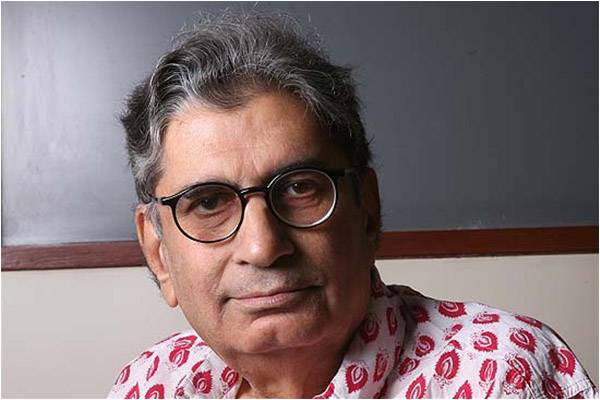

Vinod Mehta would have been flabbergasted. He would never have expected such a turnout at his funeral – the most powerful politicians, journalists, writers, cartoonists, artists, everybody except…well, in that exception possibly lies the secret of his success. The fixers and their patrons were no there.

The attendance at the Lodhi Road crematorium is not the only outpouring. Newspapers, magazines, TV channels across the country have not stopped looking at what now resembles a void. Arnab Goswami went to extraordinary lengths to pay tribute to a regular on his programmes, always waving his arm “Arnab, listen to me, Arnab”. The Times Now channel was kept open the whole morning for phone-ins, with evocative video clips of Vinod as the back drop.

I cannot remember an editor ever seen off with so much adulation.

The area for independent discourse shrank totally after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The tectonic event was marketed not as the victory of freedom but of market forces. Editors became promoters of neo conservative economic policies.

Not so much under Atal Behari Vajpayee’s NDA as under Manmohan Singh’s UPA, a new triangle of power emerged. Earlier, the editor was part of the New Delhi’s power structure. The new triangle sidelined the editor. This consisted of India Inc. in Mumbai, the US ambassador and the Prime Minister’s office. Editors were reduced to fixers. They were out of the loop on major events – unless they became promoters of these events.

What made Vinod’s funeral special, wholesome and popular was the absence of a category most common people are beginning to have a diminishing respect for – Big Business.

In some senses Vinod lived a charmed life. He escaped the dilemma of being identified this or that side of the Emergency. He came on the scene after the event.

And later, when the neo conservative ideal was ordered to be carried on editorial shoulders, Vinod cheerfully found himself an outsider. Every publication of his upto the crowning glory of Outlook, Vinod had virtually built up brick by brick, with his own hands. There was no India Inc, no media tycoon to tower above him. The glory and the brickbats were all his.

Outlook was not his means to power and wealth. In fact it was quite the opposite. It was his means to enjoy his journalism by upholding the classical, adversarial attitude towards political power and its nexus with corporate India.

Like many men of greatness, Vinod was quintessentially self made. His average, middle class family had not bestowed too much on him. Armed with a second class senior Cambridge and a third class BA from Lucknow he turned up in London.

The recycled Oxbridge elite was running out of cash by the 60s. For a new crop of Indian’s, some even from public schools, London still held promise. Would a “vilayati” dhobi mark on a certificate stand the London-bound Indian in good stead? The Kolkata boy, unlike the Lucknow Boy, found his spiritual resting place in Hampstead, demonstrating their mastery over English, despite the brown tint. The Lucknow boy of our narrative settled down in Surbiton, Surrey in the company of one Bukhari from Pakistan who spoke English like Mr Doolittle and Enamul Haq from Bangladesh, always in a dark suit, waiting for weekends when the au pair girls from Esher and Leatherhead transformed Vinod’s house into a night club.

No, London was not working out well for Vinod. In the inside pocket of his doublebreasted corduroy jacket I once found a card which I put back immediately. It was Vinod’s employee ID card for the catering department of the British Railways. I didn’t mention it to Vinod. It was not the sort of job he would like his oldest school friend to know anything about.

The weekend social clubs were his emotional outlet, but week days he caught the train to Waterloo, seeking journalists in the Fleet Street pubs, or pouring over newspapers, desperately dreaming a paper of his own in India.

After so much longing had he found his journalism that he was insecure about losing it. Once he was at the Outlook office, family, friend, party an evening at the moves, nothing would lure him away from the grind. The “parcha”, as he called his magazine, was what he lived for. The sincerity of his professionalism came across to his readers, as was clear at the funeral.

That is why the Editor we said good bye to last week deserved every bit of affection from the profession to which he had given his all without ever expecting a reward.

The attendance at the Lodhi Road crematorium is not the only outpouring. Newspapers, magazines, TV channels across the country have not stopped looking at what now resembles a void. Arnab Goswami went to extraordinary lengths to pay tribute to a regular on his programmes, always waving his arm “Arnab, listen to me, Arnab”. The Times Now channel was kept open the whole morning for phone-ins, with evocative video clips of Vinod as the back drop.

I cannot remember an editor ever seen off with so much adulation.

The area for independent discourse shrank totally after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The tectonic event was marketed not as the victory of freedom but of market forces. Editors became promoters of neo conservative economic policies.

The 'parcha', as he called his magazine, was what he lived for

Not so much under Atal Behari Vajpayee’s NDA as under Manmohan Singh’s UPA, a new triangle of power emerged. Earlier, the editor was part of the New Delhi’s power structure. The new triangle sidelined the editor. This consisted of India Inc. in Mumbai, the US ambassador and the Prime Minister’s office. Editors were reduced to fixers. They were out of the loop on major events – unless they became promoters of these events.

What made Vinod’s funeral special, wholesome and popular was the absence of a category most common people are beginning to have a diminishing respect for – Big Business.

In some senses Vinod lived a charmed life. He escaped the dilemma of being identified this or that side of the Emergency. He came on the scene after the event.

And later, when the neo conservative ideal was ordered to be carried on editorial shoulders, Vinod cheerfully found himself an outsider. Every publication of his upto the crowning glory of Outlook, Vinod had virtually built up brick by brick, with his own hands. There was no India Inc, no media tycoon to tower above him. The glory and the brickbats were all his.

Outlook was not his means to power and wealth. In fact it was quite the opposite. It was his means to enjoy his journalism by upholding the classical, adversarial attitude towards political power and its nexus with corporate India.

Like many men of greatness, Vinod was quintessentially self made. His average, middle class family had not bestowed too much on him. Armed with a second class senior Cambridge and a third class BA from Lucknow he turned up in London.

It was Vinod’s employee ID card for the catering department of the British Railways

The recycled Oxbridge elite was running out of cash by the 60s. For a new crop of Indian’s, some even from public schools, London still held promise. Would a “vilayati” dhobi mark on a certificate stand the London-bound Indian in good stead? The Kolkata boy, unlike the Lucknow Boy, found his spiritual resting place in Hampstead, demonstrating their mastery over English, despite the brown tint. The Lucknow boy of our narrative settled down in Surbiton, Surrey in the company of one Bukhari from Pakistan who spoke English like Mr Doolittle and Enamul Haq from Bangladesh, always in a dark suit, waiting for weekends when the au pair girls from Esher and Leatherhead transformed Vinod’s house into a night club.

No, London was not working out well for Vinod. In the inside pocket of his doublebreasted corduroy jacket I once found a card which I put back immediately. It was Vinod’s employee ID card for the catering department of the British Railways. I didn’t mention it to Vinod. It was not the sort of job he would like his oldest school friend to know anything about.

The weekend social clubs were his emotional outlet, but week days he caught the train to Waterloo, seeking journalists in the Fleet Street pubs, or pouring over newspapers, desperately dreaming a paper of his own in India.

After so much longing had he found his journalism that he was insecure about losing it. Once he was at the Outlook office, family, friend, party an evening at the moves, nothing would lure him away from the grind. The “parcha”, as he called his magazine, was what he lived for. The sincerity of his professionalism came across to his readers, as was clear at the funeral.

That is why the Editor we said good bye to last week deserved every bit of affection from the profession to which he had given his all without ever expecting a reward.