So wrote Albert Camus in his great novel, The Plague, and so we are learning its truth as we cower in our shelters from the Coronavirus, spreading the Covid-19 influenza that grips most of the world. We are certainly not free. I and my friends and family, as well as most Americans and it seems a large portion of the world population, are “socially distancing” ourselves from each other in order to avoid catching the virus, and more importantly I suppose, to stop the rapid spread of the disease. In the US, as in Europe, the exponential rate of new cases threatens to overwhelm our hospitals and health care workers, a scenario that almost undid China, and is now undoing Italy. The US got a very late start because of our own government’s fumbling and dissembling.

The Trump administration started in denial as the virus first attacked China. The president first claimed that shutting out all travellers from China would protect the US and there was no threat and then added a few days later that it was a Democratic Party hoax. Remember, this is an election year. While lower level health officials knew from the start that viruses do not respect borders and that a pandemic was surely on its way, it seemed this truth didn’t sink into President Trump’s mind until about two weeks ago. By then, the situation in the states of Washington, California, and New York was at the crisis stage, and state governors were the real leaders in the struggle against the pandemic. It was the governors that pushed their states into the defensive social distancing posture that most of the country is now adopting, closing bars, restaurants, and most businesses in their efforts to slow the rate of new infections.

Experts predict a tidal wave of new cases in the next month, which will at a minimum put tremendous strain on hospitals and other health care facilities and could overwhelm some states, as it has in Italy. The lack of testing capability has meant that health authorities as well as the public have no idea of the dimension of the problem. One estimate I saw is that the number of infections could be as much as 11 times greater than the presently reported number. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC), the primary federal institution charged with defending America against infectious diseases, and an institution with an impeccable reputation until recently, keeps track of the number of infections in the US and worldwide as best it can. Its figures, as of today (Monday, March 23), show the US with the third highest total cases in the world right now: China leads with almost 82,000 (and of course is where the virus seems to have originated and which locked down close to 50 million people to halt its rapid expansion); Italy is second with almost 60,000 cases; and the US is third with over 35,000.

New York, California, and Washington state account for about 2/3 of that number. Those three states are the hotspots, and New York now is reporting the most cases in the US. California is the most populous state (about 40 million) and New York is the fourth largest most densely populated state (about 20 million), so that they are hotspots is understandable. Washington is our 13th largest state and is a hotspot because the outbreak started there being a natural stopping point for visitors from China, and probably had it first infected citizens in early January. We see the geographic variation in the fact that the 2nd and 3rd largest states are still reporting low numbers of infections—Texas (334) and Florida (937). But given the weakness of our testing capacity in all the states, the number of infections is clearly some multiple of the number of reported cases. But that multiple is guesswork at present.

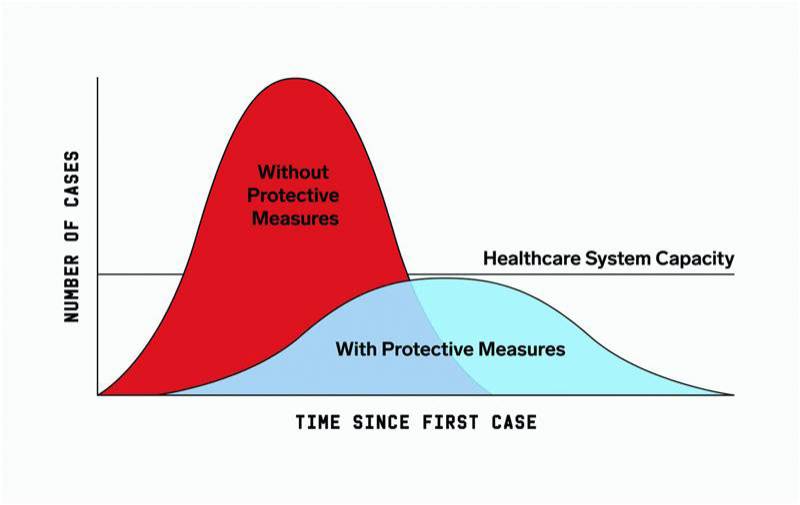

The best strategy to minimize the human cost and the economic damage of pandemics or epidemics is fairly simple intellectually but not simple at all in the real world. The graph above, which most people have seen, illustrates a strategy which most experts term “flattening the curve.” This means simply finding measures to hold below the level of infection to minimize the death toll until prophylactic measures including, hopefully, a vaccine, are developed. One of the most effective measures is the social distancing we are now undertaking. Its basic assumption is that pandemics and epidemics are inevitable and unavoidable. To minimize their impact, we want to shrink the red area in the graph into the blue area.

One basic ingredient of such a strategy must be the foresight to be prepared for pandemics and the wisdom to be completely transparent about their inevitability and the necessary measures to flatten that curve. Clearly, the Trump administration did not do either. It was not alone; Italy also is well behind that curve, and we shall see if other European countries are better prepared and transparent. On the other hand, South Korea, acted strongly and smartly to flatten that curve and did so very successfully. It is now 8th on the CDC list of countries with a large number of cases (almost 9000), but its rate of infection has declined to almost zero, and its total of deaths from the disease (111) is tied with Germany’s, well below the other countries with high numbers of cases. Other Asian countries, Singapore and Taiwan, have also done well in containing the virus.

What about my many friends in South Asia? The latest news I see is that South Asia has just passed over 500 cases of coronavirus. While the CDC list of countries show none for Pakistan, a news report is that there have been over 700 cases confirmed in the last day or two. The same report indicates that while the government has closed schools, colleges and universities, and exhorted the public to avoid public places and crowds (the social distancing needed to flatten that curve of impending infections), there is public resistance and a large degree of skepticism about the government’s concern. If this is true, Pakistan may like Italy not succeed in flattening the curve of infection and its sketchy health care system that the poor majority of the population rely on, may indeed be overrun. It will be that poor majority that pays the price for the fact that government in general has lost is credibility in Pakistan. In Bangladesh, the situation is even more alarming. CDC shows the number of cases as 33, but this is impossibly low, and friends tell me the government is deliberately giving out low numbers. And to make matters worse, Bangladeshis are being criminally misinformed by their leaders: “Coronavirus is not a deadly disease” (Foreign Minister and Health Minister); Bangladesh is “better prepared than the developed countries” (Information Minister); and the whopper of them all by what must be the sycophant of them all, coronavirus “won’t be able to do anything as long as Sheikh Hasina is here” (State Minister for Shipping).

It is instructive to look at history in the pandemic context. It is thought that the coronavirus pandemic may be the worst since the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic which infected about 500 million people around the world, which was about one fourth of the world population. The number of deaths is not known but thought to be between 17 million and 50 million. There are many differences, primarily because viruses were not known then, so comparison is difficult and can lead one astray. But one similarity that I think is important: because it began when the major nations of Europe along with the US were engaged in World War 1, with its terrible carnage, news of the outbreak was heavily censored which gave the public little warning of the coming disaster and clearly made public preparations and reactions even more difficult. It is called the “Spanish Flu” because Spain, was the only major European country not in the war, and the outbreak there was fully reported in the world’s newspapers.

Camus based The Plague on a cholera epidemic that had occurred in Oran in then-French Algeria in the mid-19th century, and on what he had read of previous epidemics in Oran including a Bubonic Plague epidemic in the 17th century. It was meant to be read on several levels including as a metaphor for how pestilence of any form, from the biological like Covid 19 to the psychological like authoritarianism can take over a society and send everybody into hiding.

The writer is a diplomat and is

Senior Policy Scholar at the

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C

The Trump administration started in denial as the virus first attacked China. The president first claimed that shutting out all travellers from China would protect the US and there was no threat and then added a few days later that it was a Democratic Party hoax. Remember, this is an election year. While lower level health officials knew from the start that viruses do not respect borders and that a pandemic was surely on its way, it seemed this truth didn’t sink into President Trump’s mind until about two weeks ago. By then, the situation in the states of Washington, California, and New York was at the crisis stage, and state governors were the real leaders in the struggle against the pandemic. It was the governors that pushed their states into the defensive social distancing posture that most of the country is now adopting, closing bars, restaurants, and most businesses in their efforts to slow the rate of new infections.

Experts predict a tidal wave of new cases in the next month, which will at a minimum put tremendous strain on hospitals and other health care facilities and could overwhelm some states, as it has in Italy. The lack of testing capability has meant that health authorities as well as the public have no idea of the dimension of the problem. One estimate I saw is that the number of infections could be as much as 11 times greater than the presently reported number. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC), the primary federal institution charged with defending America against infectious diseases, and an institution with an impeccable reputation until recently, keeps track of the number of infections in the US and worldwide as best it can. Its figures, as of today (Monday, March 23), show the US with the third highest total cases in the world right now: China leads with almost 82,000 (and of course is where the virus seems to have originated and which locked down close to 50 million people to halt its rapid expansion); Italy is second with almost 60,000 cases; and the US is third with over 35,000.

New York, California, and Washington state account for about 2/3 of that number. Those three states are the hotspots, and New York now is reporting the most cases in the US. California is the most populous state (about 40 million) and New York is the fourth largest most densely populated state (about 20 million), so that they are hotspots is understandable. Washington is our 13th largest state and is a hotspot because the outbreak started there being a natural stopping point for visitors from China, and probably had it first infected citizens in early January. We see the geographic variation in the fact that the 2nd and 3rd largest states are still reporting low numbers of infections—Texas (334) and Florida (937). But given the weakness of our testing capacity in all the states, the number of infections is clearly some multiple of the number of reported cases. But that multiple is guesswork at present.

The best strategy to minimize the human cost and the economic damage of pandemics or epidemics is fairly simple intellectually but not simple at all in the real world. The graph above, which most people have seen, illustrates a strategy which most experts term “flattening the curve.” This means simply finding measures to hold below the level of infection to minimize the death toll until prophylactic measures including, hopefully, a vaccine, are developed. One of the most effective measures is the social distancing we are now undertaking. Its basic assumption is that pandemics and epidemics are inevitable and unavoidable. To minimize their impact, we want to shrink the red area in the graph into the blue area.

One basic ingredient of such a strategy must be the foresight to be prepared for pandemics and the wisdom to be completely transparent about their inevitability and the necessary measures to flatten that curve. Clearly, the Trump administration did not do either. It was not alone; Italy also is well behind that curve, and we shall see if other European countries are better prepared and transparent. On the other hand, South Korea, acted strongly and smartly to flatten that curve and did so very successfully. It is now 8th on the CDC list of countries with a large number of cases (almost 9000), but its rate of infection has declined to almost zero, and its total of deaths from the disease (111) is tied with Germany’s, well below the other countries with high numbers of cases. Other Asian countries, Singapore and Taiwan, have also done well in containing the virus.

What about my many friends in South Asia? The latest news I see is that South Asia has just passed over 500 cases of coronavirus. While the CDC list of countries show none for Pakistan, a news report is that there have been over 700 cases confirmed in the last day or two. The same report indicates that while the government has closed schools, colleges and universities, and exhorted the public to avoid public places and crowds (the social distancing needed to flatten that curve of impending infections), there is public resistance and a large degree of skepticism about the government’s concern. If this is true, Pakistan may like Italy not succeed in flattening the curve of infection and its sketchy health care system that the poor majority of the population rely on, may indeed be overrun. It will be that poor majority that pays the price for the fact that government in general has lost is credibility in Pakistan. In Bangladesh, the situation is even more alarming. CDC shows the number of cases as 33, but this is impossibly low, and friends tell me the government is deliberately giving out low numbers. And to make matters worse, Bangladeshis are being criminally misinformed by their leaders: “Coronavirus is not a deadly disease” (Foreign Minister and Health Minister); Bangladesh is “better prepared than the developed countries” (Information Minister); and the whopper of them all by what must be the sycophant of them all, coronavirus “won’t be able to do anything as long as Sheikh Hasina is here” (State Minister for Shipping).

It is instructive to look at history in the pandemic context. It is thought that the coronavirus pandemic may be the worst since the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic which infected about 500 million people around the world, which was about one fourth of the world population. The number of deaths is not known but thought to be between 17 million and 50 million. There are many differences, primarily because viruses were not known then, so comparison is difficult and can lead one astray. But one similarity that I think is important: because it began when the major nations of Europe along with the US were engaged in World War 1, with its terrible carnage, news of the outbreak was heavily censored which gave the public little warning of the coming disaster and clearly made public preparations and reactions even more difficult. It is called the “Spanish Flu” because Spain, was the only major European country not in the war, and the outbreak there was fully reported in the world’s newspapers.

Camus based The Plague on a cholera epidemic that had occurred in Oran in then-French Algeria in the mid-19th century, and on what he had read of previous epidemics in Oran including a Bubonic Plague epidemic in the 17th century. It was meant to be read on several levels including as a metaphor for how pestilence of any form, from the biological like Covid 19 to the psychological like authoritarianism can take over a society and send everybody into hiding.

The writer is a diplomat and is

Senior Policy Scholar at the

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C