These are unprecedentedly gloomy times. Cinemas have been shut down. Many countries around the world are under lockdown – others to follow – and social distancing is being globally preached.

That means those looking for entertainment – which has almost reached therapeutic proportions for those of us privileged enough to afford it – are resorting entirely to online streaming services, even more so than before.

Again, in these dystopian circumstances celebrating silver linings can appear to be inappropriate as well. Touching any other subject that doesn’t factor in the global pandemic seems to be a self-defeating exercise.

Even so, the show must go on, and Netflix is where a lot of it is at. And it is there that Pakistan can rejoice at its first ever Netflix original.

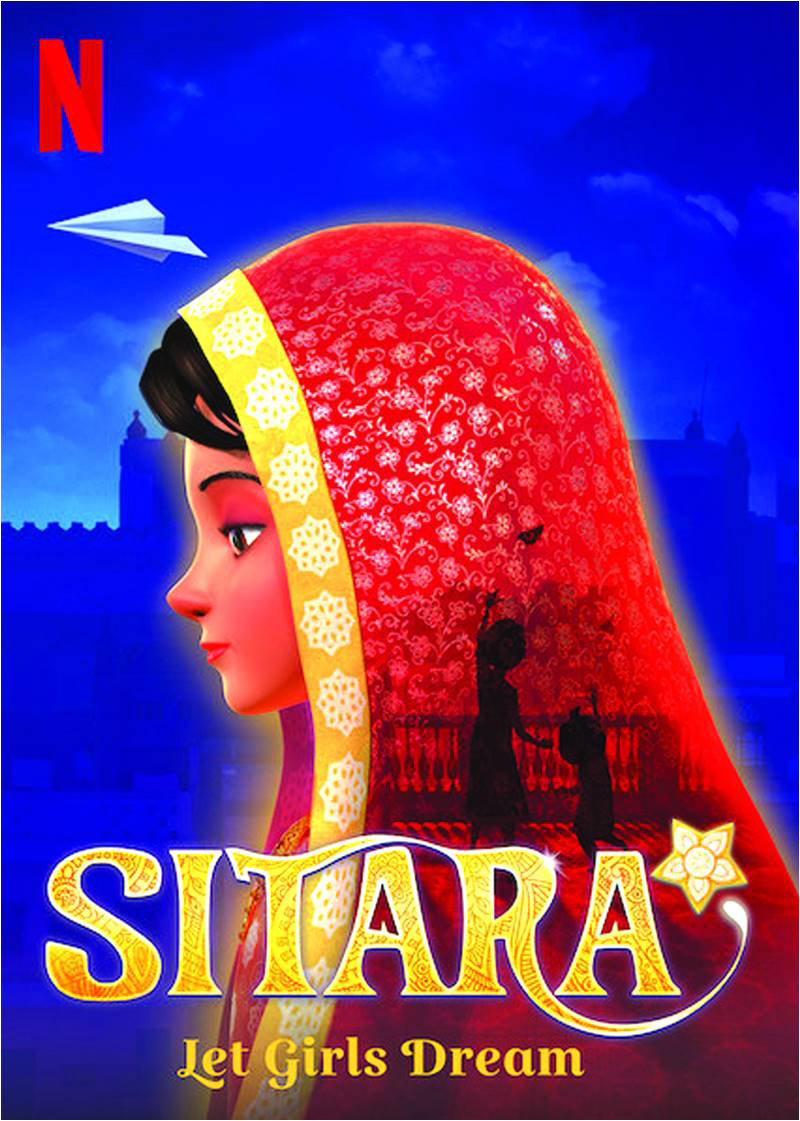

Sitara – Let Girls Dream is directed by multiple Academy and Emmy awards winning director Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, who needs absolutely no introduction as a warrior striving for women’s rights, taking on some of the ugliest aspects of Pakistan’s patriarchal status quo.

Her Oscar winning documentaries Saving Face and A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness highlighted the gruesome episodes of acid attacks and honour killings in the country.

More recently, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy has garnered local success through the animated films 3 Bahadur – which after its initial release in 2015 as Pakistan’s first computer animated feature film has since evolved into a three-part franchise that merges children entertainment with social messaging.

In Sitara, Obaid-Chinoy looks to merge feminism with animation, blending her themes on women’s rights with a message centering on children – this time unearthing a gory reality.

The 15-minute animated film is themed around child marriage, and how, in our neck of the woods, dreams of young girls are brutally squashed. Underage marriages, like many other subjects taken up by Obaid-Chinoy, is yet another ugly – and still mass prevalent – reality in the country, and like other topics centering around women and girls’ rights, the filmmaker deserves plaudits for delineating the reality.

And yet, one can’t help but be underwhelmed by a project that not only had abundance of promise, but was centered around an idea with almost unmatched relevance.

As far as art production and themes go, there would be few more pertinent than an animated film that deals with child marriage. Given the gruesomeness of the reality, handling the theme with care so as to be accessible to children was going to be a major challenge, which Sitara sets out to deal with effectively.

Narrating the story of a 14-year-old girl, Pari, who aspires to be a pilot and shares her dreams with her six-year-old sister Mehr, there are many questions that viewers might have regarding Sitara, many of which only the filmmakers can answer best.

For instance, why merely 15 minutes for a story that could have been better narrated in an hour and a half? That leads in an uncharacteristic and unrealistic change of heart at the end of the first part – in a matter of seconds – with the second part of the film being run parallel with the two-minute end credits.

Similarly, it might have been a better idea for the film to have dialogues, and not be silent. But if the filmmakers were going to take that route, then they should have shared storylines entirely through visuals – again, an ominous challenge within 15 minutes. The names and ages of the girls, for instance, are revealed in texts that aren’t actually a part of the film itself.

Furthermore, the film is set in the 1970s. Given the fact that it underlines an ill that still persists in the society, perhaps the best way to deal with it would’ve been to keep the story contemporary.

The setting of 1970s’ Old Lahore is, unquestionably, a visual treat. In that regard, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s Waadi Animations deserve the thumbs-up for another masterfully executed project.

For the rest, again, one can’t help but wonder how big the film could have been, had it not looked to squeeze in everything within 15 minutes. Given the gravity of the subject, perhaps one should expect an entirely new, thoroughly executed project by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy in the future. For this one, about dreams of flying sky-high, remains taxiing on the runway and never quite takes off.

That means those looking for entertainment – which has almost reached therapeutic proportions for those of us privileged enough to afford it – are resorting entirely to online streaming services, even more so than before.

Again, in these dystopian circumstances celebrating silver linings can appear to be inappropriate as well. Touching any other subject that doesn’t factor in the global pandemic seems to be a self-defeating exercise.

Even so, the show must go on, and Netflix is where a lot of it is at. And it is there that Pakistan can rejoice at its first ever Netflix original.

Sitara – Let Girls Dream is directed by multiple Academy and Emmy awards winning director Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, who needs absolutely no introduction as a warrior striving for women’s rights, taking on some of the ugliest aspects of Pakistan’s patriarchal status quo.

Her Oscar winning documentaries Saving Face and A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness highlighted the gruesome episodes of acid attacks and honour killings in the country.

More recently, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy has garnered local success through the animated films 3 Bahadur – which after its initial release in 2015 as Pakistan’s first computer animated feature film has since evolved into a three-part franchise that merges children entertainment with social messaging.

In Sitara, Obaid-Chinoy looks to merge feminism with animation, blending her themes on women’s rights with a message centering on children – this time unearthing a gory reality.

The setting of 1970s’ Old Lahore is, unquestionably, a visual treat

The 15-minute animated film is themed around child marriage, and how, in our neck of the woods, dreams of young girls are brutally squashed. Underage marriages, like many other subjects taken up by Obaid-Chinoy, is yet another ugly – and still mass prevalent – reality in the country, and like other topics centering around women and girls’ rights, the filmmaker deserves plaudits for delineating the reality.

And yet, one can’t help but be underwhelmed by a project that not only had abundance of promise, but was centered around an idea with almost unmatched relevance.

As far as art production and themes go, there would be few more pertinent than an animated film that deals with child marriage. Given the gruesomeness of the reality, handling the theme with care so as to be accessible to children was going to be a major challenge, which Sitara sets out to deal with effectively.

Narrating the story of a 14-year-old girl, Pari, who aspires to be a pilot and shares her dreams with her six-year-old sister Mehr, there are many questions that viewers might have regarding Sitara, many of which only the filmmakers can answer best.

For instance, why merely 15 minutes for a story that could have been better narrated in an hour and a half? That leads in an uncharacteristic and unrealistic change of heart at the end of the first part – in a matter of seconds – with the second part of the film being run parallel with the two-minute end credits.

Similarly, it might have been a better idea for the film to have dialogues, and not be silent. But if the filmmakers were going to take that route, then they should have shared storylines entirely through visuals – again, an ominous challenge within 15 minutes. The names and ages of the girls, for instance, are revealed in texts that aren’t actually a part of the film itself.

Furthermore, the film is set in the 1970s. Given the fact that it underlines an ill that still persists in the society, perhaps the best way to deal with it would’ve been to keep the story contemporary.

The setting of 1970s’ Old Lahore is, unquestionably, a visual treat. In that regard, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s Waadi Animations deserve the thumbs-up for another masterfully executed project.

For the rest, again, one can’t help but wonder how big the film could have been, had it not looked to squeeze in everything within 15 minutes. Given the gravity of the subject, perhaps one should expect an entirely new, thoroughly executed project by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy in the future. For this one, about dreams of flying sky-high, remains taxiing on the runway and never quite takes off.