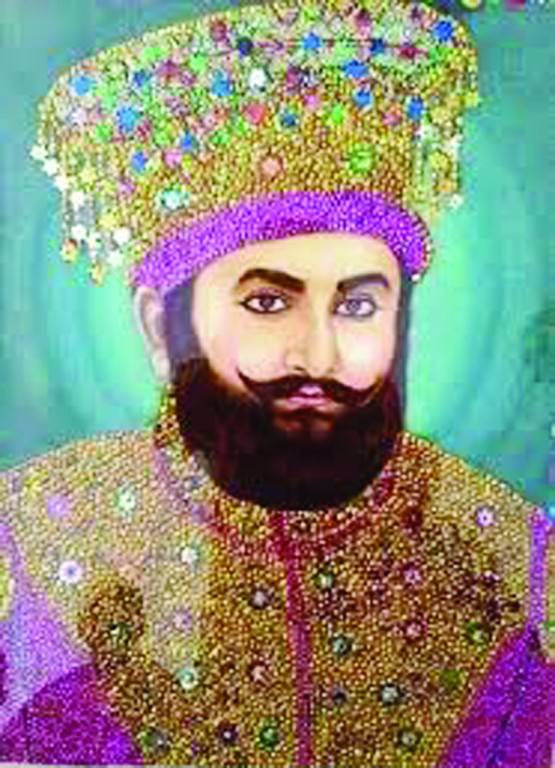

With a 108-year-long history, the Hur Movement in Sindh (1843-1951) is filled with thousands of valorous stories of mujahids (freedom fighters). The movement was initially kicked off by Sibghtullah Shah Badshah against the British colonialists, which was later on continued by his son Sibghtullah II Soreh Badshah, who chanted the famous slogan “Watan ya Kafan, Azadi ya Mout,” meaning “Land or a coffin, freedom or death” - no doubt uttered in his love for his motherland and national identity.

It was March 20, 1943 and the time was early in the morning. And the place was Hyderabad Central Jail. Soreh Badshah was proudly walking towards the gallows. The enmity of the British government against Soreh Badshah was at a peak since the very beginning. In 1930, he was implicated in 8 fake cases including a murder case, in Sukkur court. These cases were cleverly fought on his behalf by the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and he proved Soreh Badshah innocent. But as the British had decided to punish him by any means, they simply went ahead and implicated him in two more fake cases and sent him to a faraway prison, the Ratnagiri Jail. One of those two cases was of closing a man named Ibrahim Kori in a wooden box while the other one was of not possessing licenses for some outdated guns which actually were inoperable and belonged to the era of the Meerani dynasty.

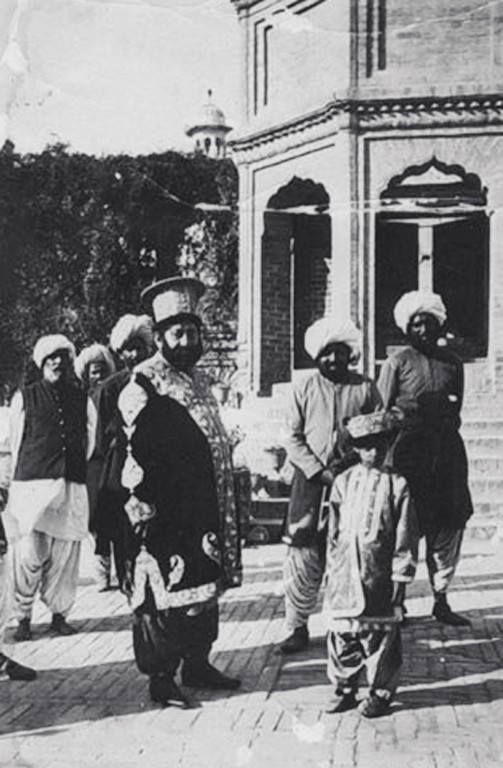

After getting freedom from Ratnagiri and East Bengal jails in 1936, when Soreh Badshah reached Sindh, he was warmly welcomed by his followers and by many of the dignitaries of that time. Such a scene was particularly vexing for the British because they had already come to know that jailing Soreh Badshah was a mistake: it had only won him sympathy among the people of Sindh.

In 1937, the Sindh Assembly election was taking place and so all the political parties of Sindh were busy in preparing for the contest. But Soreh Badshah had something else in his mind. In Pir Jo Gothh (Village of Pir), for the purpose of bringing in social reforms, he established a Panchayat of citizens which consisted of both Hindu and Muslim members. The prime purpose of that Panchayat was to resolve all local level disagreements, conflicts and issues of people without knocking on the doors of the colonial authorities for justice.

Soreh Badshah started a daily named Pir Gothh Gazette from his village Pir Jo Goth which had a Hindu editor. He also established his own power station in Pir Jo Gothh for providing electricity to the local people. The British government had reservations about all such moves by Soreh Badshah so they took it all even more seriously at this time.

Pir Gothh Gazette as a newspaper was disseminating ideas of Hindu-Muslim brotherhood and such a thing was unpalatable for the leaders of newly built Muslim League in Sindh. In 1939-40 they became implicated in the ‘Masjid Manzilgah riots’ in Sukkur, which indicated a policy of exacerbating communal tensions for political reasons. Soreh Badshah, for his part, said that Hindus and Muslims are equal citizens of Sindh so they have equal rights to either go to a Masjid (for Muslims) or Mandir (for Hindus) for their worship. He ordered his followers to safeguard the lives and properties of Hindus in Sindh but it was a late call because by then, the violent Mureeds of a fanatic religious group in Sukkur had killed around 57 Hindus in two days of rioting.

Pir Jo Gothh was situated in the Khairpur state, which was fairly subservient to the colonialists. The British had sent the state’s ruler Mir Faiz Muhammad Khan II to a mental hospital in Lucknow by declaring him a mental patient while his son Mir Ali Murad Khan II was deceitfully sent to England for studies. When all the hurdles were cleared, they brought in a strange man from Lucknow to rule Khairpur Riyasat.

During the rule of that puppet ruler, propaganda started against Soreh Badshah: that he was planning to occupy the Khairpur state and wanted to be a king in Sindh. The British political agents of Khairpur kept sending fake reports against him to Sindh’s governor Sir Lancelot Graham on a monthly basis but he kept ignoring such reports while he remained governor. When Sir Lancelot Graham was replaced by a new governor Sir Hugh Dow, the circumstances became different as he issued orders to the British colonial state apparatus to take serious action against Soreh Badshah.

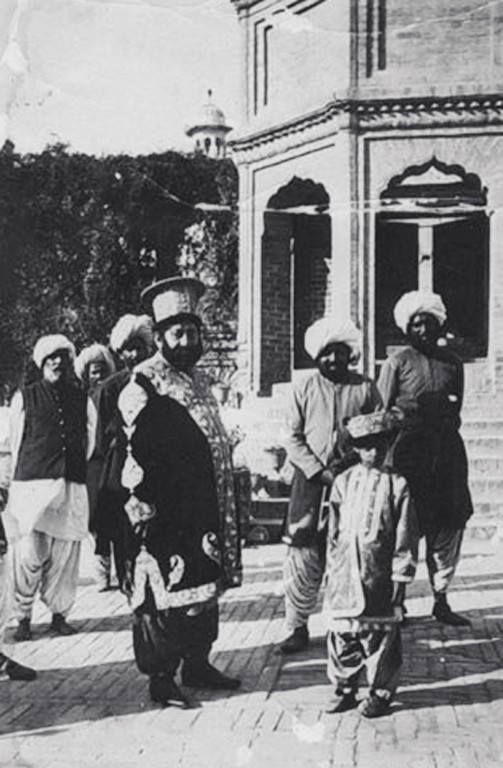

In such circumstances, Soreh Badshah decided to meet Sir Hugh Dow so he dressed up in his distinctive gadi-nasheen garb and was accompanied by the chief minister of the Sindh cabinet. He went to Karachi to meet the governor. In that one-to-one meeting, Dow said to him “You are recruiting fighters for rebellion against us” while Soreh Badshah replied “Our fighters are also social volunteers like Congress has - and they are here to help the society in times of natural disasters.”

After that meeting Hugh Dow sent a report to Viceroy Lord Linlithgow in which he wrote that the amount of pure gold and precious jewels that he saw in Badshah’s dress and crown were greater than even those of the British crown prince – and so this Pir (Soreh Badshah) wanted to be king in Sindh.

Soreh Badshah along with his family shifted to Ghirrang Banglow near Sanghar. This story did not end there. Now the people of Bugti State in Sanghar who were loyal to the British government started writing lettersin which they mentioned the presence of Soreh Badshah in Sanghar as a risk for them. On the basis of such misreporting, Hugh Dow passed orders that the Pir must leave Sanghar at once and move to Karachi alone. Soreh Badshah obeyed such orders. He went to Karachi and started living there in a bungalow.

During his stay in Karachi, Soreh Badshah continuously kept questioning the authorities. He wanted to know under which act/law he had been parted from his family. One day he asked the governor to permit him to go to meet his family but was refused. He then left for Sanghar and Pir Jo Gothh without informing anyone. On this, an angry governor ordered the Superintendent of Police Sukkur to arrest Soreh Badshah and sent him back to Karachi.

October 14, 1941, was the day when Sukkur police arrested the Pir when he was on his way to his lands. He was sent to Karachi by rail and detained in Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah’s residency, who was a minister in that time’s Sindh cabinet.

He was jailed there till January 14, 1943, and then a case of rebellion against the British government was lodged against him. Eventually, he was declared a rebel and hanged in Hyderabad jail on March 20, 1943.

The writer is a freelance contributor and may be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com

It was March 20, 1943 and the time was early in the morning. And the place was Hyderabad Central Jail. Soreh Badshah was proudly walking towards the gallows. The enmity of the British government against Soreh Badshah was at a peak since the very beginning. In 1930, he was implicated in 8 fake cases including a murder case, in Sukkur court. These cases were cleverly fought on his behalf by the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and he proved Soreh Badshah innocent. But as the British had decided to punish him by any means, they simply went ahead and implicated him in two more fake cases and sent him to a faraway prison, the Ratnagiri Jail. One of those two cases was of closing a man named Ibrahim Kori in a wooden box while the other one was of not possessing licenses for some outdated guns which actually were inoperable and belonged to the era of the Meerani dynasty.

After getting freedom from Ratnagiri and East Bengal jails in 1936, when Soreh Badshah reached Sindh, he was warmly welcomed by his followers and by many of the dignitaries of that time. Such a scene was particularly vexing for the British because they had already come to know that jailing Soreh Badshah was a mistake: it had only won him sympathy among the people of Sindh.

In 1937, the Sindh Assembly election was taking place and so all the political parties of Sindh were busy in preparing for the contest. But Soreh Badshah had something else in his mind. In Pir Jo Gothh (Village of Pir), for the purpose of bringing in social reforms, he established a Panchayat of citizens which consisted of both Hindu and Muslim members. The prime purpose of that Panchayat was to resolve all local level disagreements, conflicts and issues of people without knocking on the doors of the colonial authorities for justice.

Soreh Badshah started a daily named Pir Gothh Gazette from his village Pir Jo Goth which had a Hindu editor. He also established his own power station in Pir Jo Gothh for providing electricity to the local people. The British government had reservations about all such moves by Soreh Badshah so they took it all even more seriously at this time.

Pir Gothh Gazette as a newspaper was disseminating ideas of Hindu-Muslim brotherhood and such a thing was unpalatable for the leaders of newly built Muslim League in Sindh. In 1939-40 they became implicated in the ‘Masjid Manzilgah riots’ in Sukkur, which indicated a policy of exacerbating communal tensions for political reasons. Soreh Badshah, for his part, said that Hindus and Muslims are equal citizens of Sindh so they have equal rights to either go to a Masjid (for Muslims) or Mandir (for Hindus) for their worship. He ordered his followers to safeguard the lives and properties of Hindus in Sindh but it was a late call because by then, the violent Mureeds of a fanatic religious group in Sukkur had killed around 57 Hindus in two days of rioting.

Pir Jo Gothh was situated in the Khairpur state, which was fairly subservient to the colonialists. The British had sent the state’s ruler Mir Faiz Muhammad Khan II to a mental hospital in Lucknow by declaring him a mental patient while his son Mir Ali Murad Khan II was deceitfully sent to England for studies. When all the hurdles were cleared, they brought in a strange man from Lucknow to rule Khairpur Riyasat.

During the rule of that puppet ruler, propaganda started against Soreh Badshah: that he was planning to occupy the Khairpur state and wanted to be a king in Sindh. The British political agents of Khairpur kept sending fake reports against him to Sindh’s governor Sir Lancelot Graham on a monthly basis but he kept ignoring such reports while he remained governor. When Sir Lancelot Graham was replaced by a new governor Sir Hugh Dow, the circumstances became different as he issued orders to the British colonial state apparatus to take serious action against Soreh Badshah.

In such circumstances, Soreh Badshah decided to meet Sir Hugh Dow so he dressed up in his distinctive gadi-nasheen garb and was accompanied by the chief minister of the Sindh cabinet. He went to Karachi to meet the governor. In that one-to-one meeting, Dow said to him “You are recruiting fighters for rebellion against us” while Soreh Badshah replied “Our fighters are also social volunteers like Congress has - and they are here to help the society in times of natural disasters.”

After that meeting Hugh Dow sent a report to Viceroy Lord Linlithgow in which he wrote that the amount of pure gold and precious jewels that he saw in Badshah’s dress and crown were greater than even those of the British crown prince – and so this Pir (Soreh Badshah) wanted to be king in Sindh.

The cases were cleverly fought on his behalf by the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and he proved Soreh Badshah innocent. But as the British had decided to punish him by any means, they simply went ahead and implicated him in two

more fake cases

Soreh Badshah along with his family shifted to Ghirrang Banglow near Sanghar. This story did not end there. Now the people of Bugti State in Sanghar who were loyal to the British government started writing lettersin which they mentioned the presence of Soreh Badshah in Sanghar as a risk for them. On the basis of such misreporting, Hugh Dow passed orders that the Pir must leave Sanghar at once and move to Karachi alone. Soreh Badshah obeyed such orders. He went to Karachi and started living there in a bungalow.

During his stay in Karachi, Soreh Badshah continuously kept questioning the authorities. He wanted to know under which act/law he had been parted from his family. One day he asked the governor to permit him to go to meet his family but was refused. He then left for Sanghar and Pir Jo Gothh without informing anyone. On this, an angry governor ordered the Superintendent of Police Sukkur to arrest Soreh Badshah and sent him back to Karachi.

October 14, 1941, was the day when Sukkur police arrested the Pir when he was on his way to his lands. He was sent to Karachi by rail and detained in Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah’s residency, who was a minister in that time’s Sindh cabinet.

He was jailed there till January 14, 1943, and then a case of rebellion against the British government was lodged against him. Eventually, he was declared a rebel and hanged in Hyderabad jail on March 20, 1943.

The writer is a freelance contributor and may be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com