The details of the project for reconstruction and settlement of the affected areas were kept secret so it is not possible now to analyze their benefit. But one thing was clear: that this project was prepared by government officials, whether they were from then-East Pakistan or from West Pakistan. There was no intervention of the will of the representatives from East Pakistan or the affected areas in the preparation of this plan. As for the competence and dutifulness of the government officials, the President himself did not appear to be satisfied with it - otherwise why would he have said that he was seriously thinking about giving this work over to the Army?

The indirect manner in which General Yahya Khan had expressed a lack of confidence upon the government officials had also been the experience of the whole nation in the prior 22 years. In this situation, could one have said with certainty that the settlement plan which these gentlemen had prepared would really benefit the affected areas? And was it not possible to consult also the political leaders, social workers and the representatives of the medical associations, engineering associations and teachers associations of East Pakistan? These people were much more informed of the local conditions than government officials. They knew well about which things the people needed and how suitable it would have been to spend what amount upon which account. Perhaps the expenses could have been reduced, as well as conveniences created in work with the cooperation of these groups of people.

But it was not to be.

As far as handing over this work to the army was concerned, no patriotic Pakistani could have denied that the Pakistani military had accomplished many things in the past. But it was also true that the reconstruction and settlement of the affected areas was such a huge task that one group alone could not complete it – however much “prepared and honest” they could be. For this, the practical cooperation of the whole country was needed.

If memory serves correctly, perhaps there also used to be a Flood Commission in Pakistan in those days. The members of this Commission had visited China and many other countries, where the destructions of floods and cyclones had been overcome with the cooperation of the people. Their reports must have reached the eyes of the authorities. Now it is absurd to ask why those reports were not acted upon at that time but if they contained a few recommendations for public cooperation, it would have been suitable to reflect upon them. After all, it was with public cooperation indeed that China was able to redirect the rivers and end the force of its flooding problem.

Till that time, the basic weakness of construction projects in Pakistan had been that the planners made do with merely the performance of the official staff and did not consider worthy of attention the cooperation of people for whom all those projects were made. The gulf of suspicion and mistrust between the bureaucracy and the people became wider with time. The people remained aloof thinking that these were not questions of public interest but were the pastimes of the kings and the courts – what did they have to do with them?

The bureaucracy considered the people and their representatives as illiterate and foolish; or they worried that if the latter were included in the work, then the paths of personal gain would be obstructed, so they thought it an insult even to consult the ordinary people.

President Yahya Khan used to say in those days that he was not “hungry for political power” but wanted to transfer the law and order of the country to the representatives chosen by the people as soon as possible. In this situation, it was indeed more necessary to consult the authentic representatives of the people so that the continuity of the works was not broken and nobody could present the excuse after taking power that since they were not consulted in the implementation of this project, they would not run it.

At that time many – not just on the Left - had proposed that in order to make the reconstruction project of then-East Pakistan successful, an empowered joint committee of political leaders, social workers, engineers, teachers, doctors, students, journalists and labour and peasant leaders of various schools of thought be made. This committee would also include representatives of the army and the government and all the powers of settlement as well as the responsibilities would be handed over to it. Had the government wanted that every class, sect and group in the country consider the settlement of the afflicted their national duty; that a feeling of participation in the construction project be created within every person; that the articles received in aid be spared from loot and plunder by selfish elements and reach the deserving; that the government officials were not made the target of hate and reproach – it would have composed such a joint committee at the national level.

It is also now hard to disagree with what the President said at that time: i.e. the destruction in East Pakistan should not be used as political football. But in this respect one is forced to reflect in hindsight upon the news of little-known activities of a few foreign powers which were published in newspapers of those days, which created great apprehension. For example the engagements of the then-US ambassador to Pakistan. The political leaders of East Pakistan also objected to the presence of British forces. The Dhaka newspaper Azad revealed at the time that the American government was ready to give aid for the control of floods and cyclones and other development projects but was desirous of establishing a naval base at Chittagong in lieu of it.

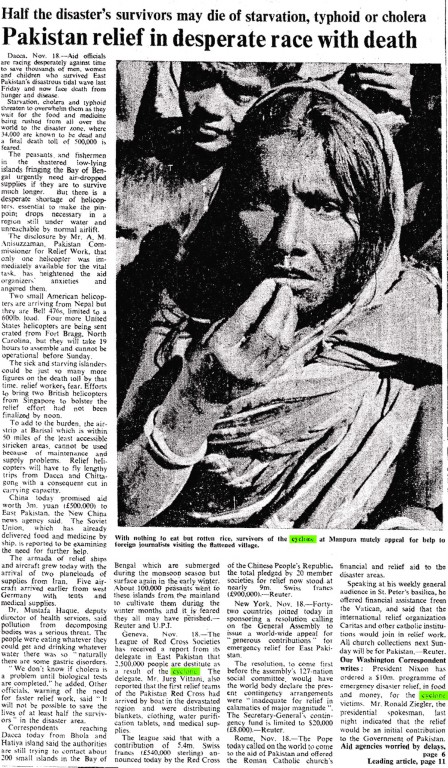

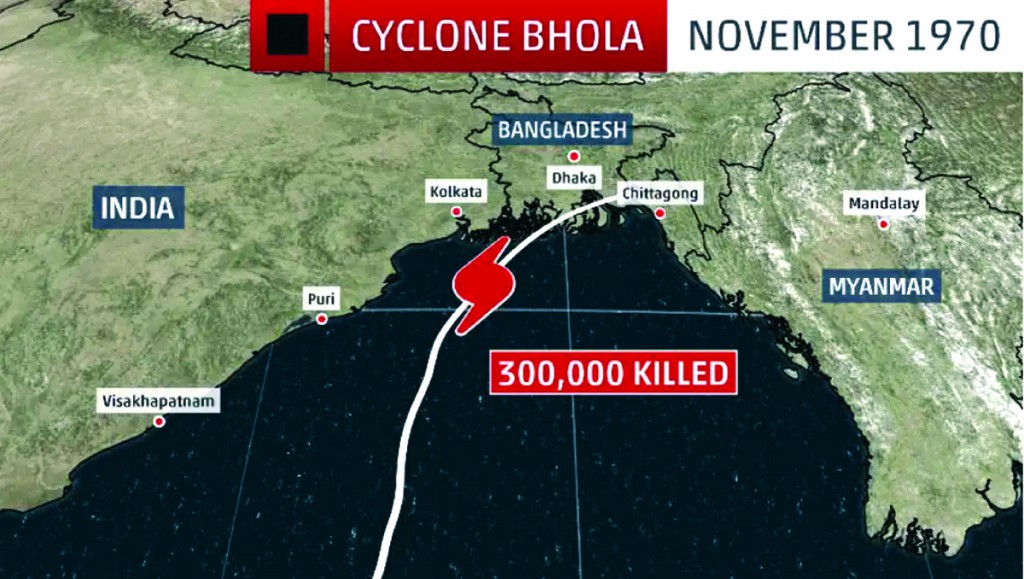

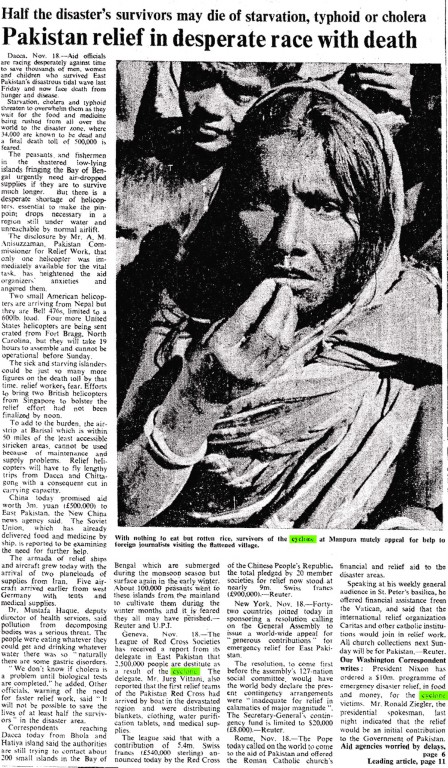

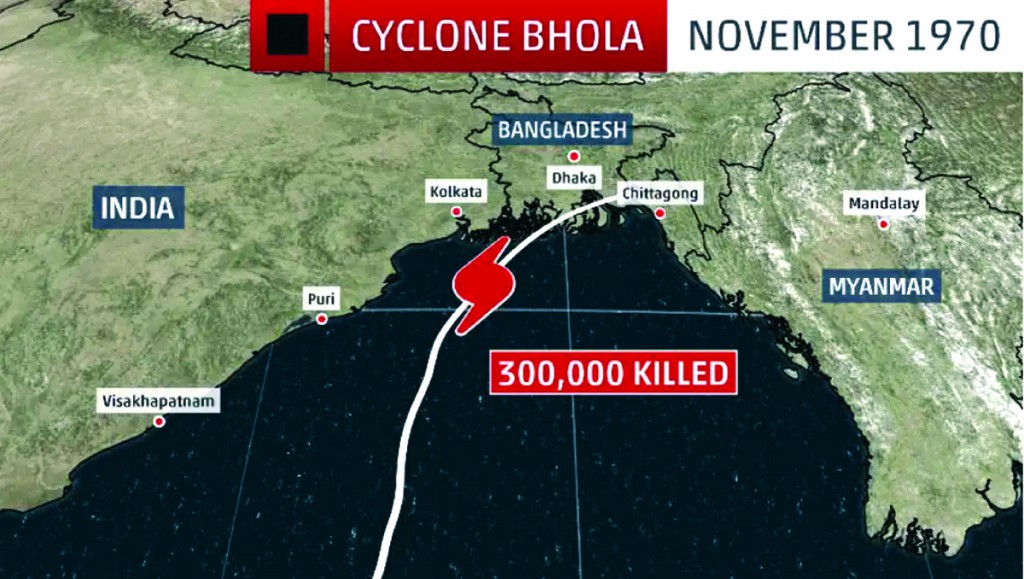

However all of this came to naught as the Awami League, headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, swept to a landslide victory in the national elections on December 7, 1970, in part because of dissatisfaction over failure of the relief efforts by the national government. The elections for nine national assembly and eighteen provincial assembly seats had to be postponed until January 18, 1971 as a result of the storm.

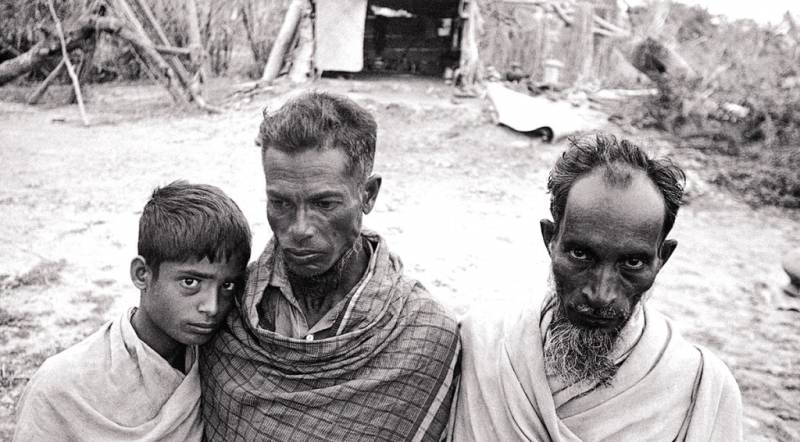

The government’s handling of the relief efforts helped exacerbate the bitterness felt in then-East Pakistan, swelling the resistance movement there. Funds only slowly got through, and transport was slow in bringing supplies to the devastated regions. As tensions increased in March 1971, foreign personnel evacuated because of fears of violence. The situation deteriorated further and developed into a liberation struggle in March. This conflict widened into the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 in December and concluded with the creation of Bangladesh. This was one of the first times that a natural event helped to trigger a civil war.

Meanwhile it was left to Ghulam Muhammad Qasir, the 29 year old Pashtun Urdu poet from Dera Ismail Khan to pen a dirge for the hapless victims of ‘Noah’s Flood’:

Maut voh Nooh ka toofaan hai ke jis ke aage

Zeest kohsaar ki choti ke sivaa kuch bhi nahi

Khamushi goonje toa phir saut-o-sadaa kuch bhi nahi

Zeest ki jins-e-garaan maut ki tehveel mein hai

Lashkar-e-umar-e-ravaan rahguzar-e-Neel mein hai

(Death is that Noah’s flood before which

Life is nothing but a mountain peak

If silence echoes, nothing are the sound and the shriek

The costly article of life is in death’s custody

Within the Nile’s pathway lies the passing life’s army)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

The indirect manner in which General Yahya Khan had expressed a lack of confidence upon the government officials had also been the experience of the whole nation in the prior 22 years. In this situation, could one have said with certainty that the settlement plan which these gentlemen had prepared would really benefit the affected areas? And was it not possible to consult also the political leaders, social workers and the representatives of the medical associations, engineering associations and teachers associations of East Pakistan? These people were much more informed of the local conditions than government officials. They knew well about which things the people needed and how suitable it would have been to spend what amount upon which account. Perhaps the expenses could have been reduced, as well as conveniences created in work with the cooperation of these groups of people.

But it was not to be.

As far as handing over this work to the army was concerned, no patriotic Pakistani could have denied that the Pakistani military had accomplished many things in the past. But it was also true that the reconstruction and settlement of the affected areas was such a huge task that one group alone could not complete it – however much “prepared and honest” they could be. For this, the practical cooperation of the whole country was needed.

The bureaucracy considered the people and their representatives as illiterate and foolish; or they worried that if the latter were included in the work, then the paths of personal gain would be obstructed

If memory serves correctly, perhaps there also used to be a Flood Commission in Pakistan in those days. The members of this Commission had visited China and many other countries, where the destructions of floods and cyclones had been overcome with the cooperation of the people. Their reports must have reached the eyes of the authorities. Now it is absurd to ask why those reports were not acted upon at that time but if they contained a few recommendations for public cooperation, it would have been suitable to reflect upon them. After all, it was with public cooperation indeed that China was able to redirect the rivers and end the force of its flooding problem.

Till that time, the basic weakness of construction projects in Pakistan had been that the planners made do with merely the performance of the official staff and did not consider worthy of attention the cooperation of people for whom all those projects were made. The gulf of suspicion and mistrust between the bureaucracy and the people became wider with time. The people remained aloof thinking that these were not questions of public interest but were the pastimes of the kings and the courts – what did they have to do with them?

The bureaucracy considered the people and their representatives as illiterate and foolish; or they worried that if the latter were included in the work, then the paths of personal gain would be obstructed, so they thought it an insult even to consult the ordinary people.

President Yahya Khan used to say in those days that he was not “hungry for political power” but wanted to transfer the law and order of the country to the representatives chosen by the people as soon as possible. In this situation, it was indeed more necessary to consult the authentic representatives of the people so that the continuity of the works was not broken and nobody could present the excuse after taking power that since they were not consulted in the implementation of this project, they would not run it.

At that time many – not just on the Left - had proposed that in order to make the reconstruction project of then-East Pakistan successful, an empowered joint committee of political leaders, social workers, engineers, teachers, doctors, students, journalists and labour and peasant leaders of various schools of thought be made. This committee would also include representatives of the army and the government and all the powers of settlement as well as the responsibilities would be handed over to it. Had the government wanted that every class, sect and group in the country consider the settlement of the afflicted their national duty; that a feeling of participation in the construction project be created within every person; that the articles received in aid be spared from loot and plunder by selfish elements and reach the deserving; that the government officials were not made the target of hate and reproach – it would have composed such a joint committee at the national level.

It is also now hard to disagree with what the President said at that time: i.e. the destruction in East Pakistan should not be used as political football. But in this respect one is forced to reflect in hindsight upon the news of little-known activities of a few foreign powers which were published in newspapers of those days, which created great apprehension. For example the engagements of the then-US ambassador to Pakistan. The political leaders of East Pakistan also objected to the presence of British forces. The Dhaka newspaper Azad revealed at the time that the American government was ready to give aid for the control of floods and cyclones and other development projects but was desirous of establishing a naval base at Chittagong in lieu of it.

However all of this came to naught as the Awami League, headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, swept to a landslide victory in the national elections on December 7, 1970, in part because of dissatisfaction over failure of the relief efforts by the national government. The elections for nine national assembly and eighteen provincial assembly seats had to be postponed until January 18, 1971 as a result of the storm.

The government’s handling of the relief efforts helped exacerbate the bitterness felt in then-East Pakistan, swelling the resistance movement there. Funds only slowly got through, and transport was slow in bringing supplies to the devastated regions. As tensions increased in March 1971, foreign personnel evacuated because of fears of violence. The situation deteriorated further and developed into a liberation struggle in March. This conflict widened into the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 in December and concluded with the creation of Bangladesh. This was one of the first times that a natural event helped to trigger a civil war.

Meanwhile it was left to Ghulam Muhammad Qasir, the 29 year old Pashtun Urdu poet from Dera Ismail Khan to pen a dirge for the hapless victims of ‘Noah’s Flood’:

Maut voh Nooh ka toofaan hai ke jis ke aage

Zeest kohsaar ki choti ke sivaa kuch bhi nahi

Khamushi goonje toa phir saut-o-sadaa kuch bhi nahi

Zeest ki jins-e-garaan maut ki tehveel mein hai

Lashkar-e-umar-e-ravaan rahguzar-e-Neel mein hai

(Death is that Noah’s flood before which

Life is nothing but a mountain peak

If silence echoes, nothing are the sound and the shriek

The costly article of life is in death’s custody

Within the Nile’s pathway lies the passing life’s army)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com