Those who opposed the war before it was fought had said it numerous times. It took 16 years for the US military to confess that Iran won the war.

This admission is contained in a two-volume report that was issued by the US Army in 2019. The report was largely ignored but is finally in the news.

Iraq and Iran had a long history of rivalry. It reached its peak when the two countries went to war in 1980, a year after Ayatollah Khomeini took over the reins of power in Tehran. Iraq was governed by Saddam Hussain. He had a tough childhood, had never served in the military, and was a lawyer by training.

Concerned that a theocratic Iran may foment a rebellion among the Shia in Iraq, which accounted for a majority of the population, he attacked Iran. The bitter enemies fought for eight years. More than a million people were killed in the Iraq-Iran War but it had an inconclusive ending.

Iraq ran up a debt in billions and attacked Kuwait in 1990 to seize its oil field, precipitating the Gulf War. The US, concerned that after grabbing Kuwait’s oil fields, he will go after the Saudi Arabian oil fields, created a coalition of forces to drive him out.

The coalition was successful, despite the firing of SCUD missiles by Saddam into Saudi Arabia. I remember visiting Dhahran in Saudi Arabia in 1994 and seeing remnants of the Patriot missiles on display in a hotel lobby.

An uneasy calm returned to the region. It was shattered when 9/11 happened. In retaliation and self-defense, the US attacked the Taliban in Afghanistan, since they were found to be giving refuge to the al-Qaeda forces led by Osama bin Laden. The Taliban were deposed in a couple of months.

But the fear and anger that had been roused in the US was not quelled. Two years after 9/11, the US decided to hit Iraq with its full strength, claiming that Iraq was linked with al-Qaeda which had carried out the 9/11 attacks and further claiming that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction which posed an imminent danger to the West. At the time, 72 percent Americans supported the invasion.

On March 20, 2003, the US hit Iraq with bombs and missiles from all directions and invaded it with 130,000 troops. Unable to handle all this “Shock and Awe,” Baghdad fell in just 21 days.

In a symbolic gesture that reverberated around the globe, US troops toppled Saddam’s statue at Firdous Square in Baghdad on April 9.

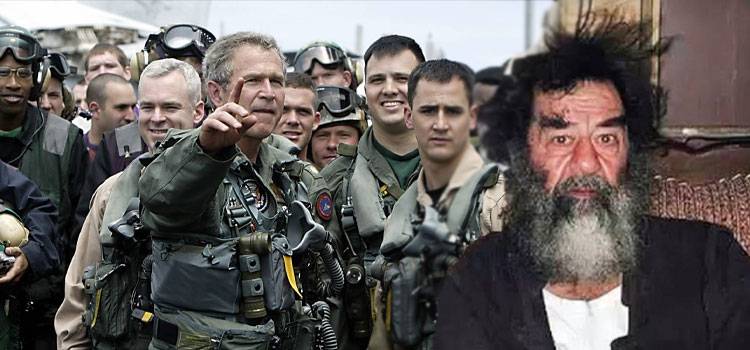

On May 1, President George W. Bush flew onto the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in a Lockheed S-3 Viking, 35 miles off the coast of San Diego. Under a “Mission Impossible” banner, he declared that major combat operations were over.

Unlike its military operations during the Gulf War of 1991, where a coalition of countries had joined hands with the US, this time the US was prepared to go in alone. As a formality, it sent General Colin Powell, the US Secretary of State, to the UN to prove that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and that those weapons posed a threat to the West. His speech did not convince anyone except the UK.

At home, large rallies were held in February 2003 in multiple cities to prevent the US from going to war. Along with hundreds of thousands of others, my wife and I participated in a large rally in San Francisco in front of City Hall to stop the war from taking place.

According to TIME magazine, the largest coordinated protests were held in February in several major cities of the world.

But Bush, working hand-in-glove with Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice, was not listening. Richard Clarke, the National Security Council’s counterterrorism coordinator was dumbfounded. He said that attacking Iraq when it had nothing to do with 9/11 was just as nonsensical as invading Mexico after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 12/7 in 1941.

As far back as August 2002, sensing an imminent invasion, Brent Scowcroft had published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal. He wrote presciently, “Our nation is presently engaged in a debate about whether to launch a war against Iraq. Leaks of various strategies for an attack on Iraq appear with regularity…[but] there is scant evidence to tie Saddam to terrorist organisations, and even less to the Sept 11 attacks. Indeed, Saddam’s goals have little in common with the terrorists who threaten us, and there is little incentive for him to make common cause with them…The United States could certainly defeat the Iraqi military and destroy Saddam’s regime. But it would not be a cakewalk. On the contrary, it undoubtedly would be very expensive – with serious consequences for the US and global economy –and could as well be bloody.”

The Iraq War damaged the reputation of the US throughout the globe, most notably in the Arab World. I was in Riyadh just a few months after the war. One uniformed officer asked me, “When is the cowboy going to get out of Iraq?” George W. Bush had come to symbolise the American cowboy in the Arab mind.

Two decades after the war started, the Iraq war is considered an unmitigated disaster in the US, both in terms of treasure and lives. The financial cost for the US has been estimated by experts at Harvard University at $3 trillion, sufficient to completely wipe out the US budget deficit for two years. Nearly 4,500 Americans died in the war and 32,000 were wounded.

Americans who fought in the war have been speaking against the war, saying they were sent into a country of which they neither knew the culture nor the terrain.

For Iraq, the devastation was beyond comprehension. Experts at Brown University estimate that more than 800,000 people died as a direct result of fighting. Of those, more than 335,000 were civilians. Worse, “another 21 million people have been displaced due to violence.” Today, just about everyone in Iraq has lost someone due to the US invasion.

Law and order have disappeared from a country that was once considered the safest Arab state. Chaos reigns on the streets. Two large cities – Mosul and Fallujah – are largely destroyed and damage is visible in almost every major city in central and northern Iraq.

Corruption is widespread, with Iraq ranking 157th among 180 countries in the corruption index developed by Transparency International. One third of the young are unemployed, according to the World Bank and the International Labor Organization.

The ultimate mea culpa comes from Max Boot, one of the strongest advocates of the war. He writes, “I would never have supported military action had I known that he was not actually building weapons of mass destruction, but what I really wanted was to get rid of Iraq’s cruel dictator, not just his purported weapons program. One of the central arguments that I and other supporters of an invasion made was that regime change could trigger a broader democratic transformation in the Middle East. I now cringe when I read some of the articles I wrote at the time. ‘This could be the chance to right the scales, to establish the first Arab democracy, and to show the Arab people that America is as committed to freedom for them as we were for the people of Eastern Europe’.”

Like many analysts, he believed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. He also believed that democracy could be imposed by force. He forgot that democratic institutions did not exist in Iraq nor could they be created overnight. Iran had been ruled by dictators and absolute monarchs for decades. To add to its woes, the US demolished the two institutions that had kept Iraq together, the Baath Party and the Army.

Andrew Bacevich, Professor Emeritus at Boston University, notes that the Iraq War was “the acme of American military folly,” right after the Vietnam War. It was launched on the naïve assumption that American troops would be welcomed as liberators not just in Iraq but in the entire Arab world.

Bacevich writes: “Operation Iraqi Freedom instead produced a mournful legacy of death and destruction that destabilised the region. For a time, supporters of the war consoled themselves with the thought that the removal from power of the Iraqi tyrant Saddam Hussein had made the world a better place. Today, no amount of sophistry can sustain that claim.”

Melvyn Leffler, Professor Emeritus at Virginia University, concludes in his new book that the invasion was based on fear and hubris. Fear born out of the 9/11 attacks, the first on US soil since Pearl Harbor, and hubris, arising from its self-assessment of its preeminence in the globe.

Peter Bergen, in an opinion piece for CNN, recently interviewed George Piro, the FBI agent who interrogated Saddam Hussain after he had been captured. Bergen writes: “The dictator’s discussions with Piro confirmed that the Iraq War was America’s original sin during the dawn of the 21st century — a war fought under false assumptions, a conflict that killed thousands of American troops and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.”

George Piro, a young Lebanese American who worked in the FBI, stated that Saddam felt his biggest enemy was Iran. All his talk about his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) was designed to scare Iran. His biggest fear was that if Iran discovered how weak he was, they would invade southern Iraq and take it.

The reality is that whatever WMDs were in Iraq’s possession were destroyed by the UN inspectors. Saddam knew that Iraq, despite his boastful rhetoric, did not have the capacity to fight the US. He was neither a strategist or a tactician. Thus, he severely misjudged US intentions.

The US was convinced it could depose Saddam militarily in a matter of weeks and free the Iraqis from his despotic and tyrannical rule. After that, it felt that it would create a democratic dispensation which would make Iraq a beacon of freedom in the entire Arab world.

It did not realise that deposing Saddam and the Baath Party would open a Pandora’s Box. It did not heed the warning by Egypt’s foreign minister, who was the head of the Arab League, that invading Iraq “would open the gates of hell.”

Far from being a “slam dunk,” as one US leader had predicted it would be, the war turned out to be an impossible assignment, political as well as military. The US army history of the Iraq War, on page 653 of Volume 1, provides this stark assessment of how the situation deteriorated in a manner that no one in the US military had anticipated.

“From December 2003 to December 2006, the war in Iraq evolved from a relatively loose insurgency against the U.S.-led coalition into a horrific ethno-sectarian civil war that tore at the fabric of Iraqi society and threatened Iraq’s very existence as a unitary state. This 3-year period, which began with the false hope that Saddam Hussein’s capture in December 2003 would cause the insurgency to evaporate, quickly entered a demoralising stage caused by the April 2004 uprisings and the Abu Ghraib prison scandal. Had it not been for the response of the departing 1st Armored Division as an unplanned operational reserve, the coalition might well have suffered a strategic defeat along the lines of the 1968 Tet offensive in Vietnam.”

Once Saddam had been deposed, in-fighting broke out all over Iraq, with sinister sectarian and ethnic overtones, the likes of which Iraq had not seen in decades. Out of the carnage arose a new threat, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

It left al-Qaeda behind in the dust. An unknown man, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, rose to become the head of ISIS. He declared himself the caliph of the global Muslim nation or Ummah.

It wasn’t just the creation of ISIS that stunned the world. The US invasion had given birth to a new jihadist movement. The cruelty with which people were tortured and murdered, and their beheadings captured on videos, left the world stunned and bewildered. A depression set in. Iraqis began to reminisce and yearn for the days when Saddam ruled Iraq.

Iran was the only country left smiling after the Iraq War. Its main rival had been demolished by another rival, without it having to fire a single shot, lose a single soldier, or spend a dime.

Writing in TIME magazine, the authors of the official US report on the Iraq War say, “Iranian-backed militias, on the Iraqi payroll, now outnumber the Iraqi Army. The Ministry of Defense now includes officers and generals who are designated terrorists. Iranian aligned militias have captured state resources through political representation in Parliament and by controlling key posts in lucrative ministries. Iran’s influence now waxes in an uninterrupted arc from Tehran to the Mediterranean, traipsing across Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.”

Iraq’s largest trading partner is now Iran and the two countries have friendly ties. Their leaders have begun visiting each other.

President Bush did not accomplish his mission. He ended up accomplishing the opposite, letting Iran establish primacy over Iraq and the region. The Iraq War is yet another validation of the Law of Unintended Consequences which runs throughout history.

The US army’s history of the war ends with this damning conclusion: “In a way, it would be reassuring to believe that the mistakes the United States made in the Iraq War were the result of unintelligent leaders making poor decisions. If that were so, then the United States could be assured of avoiding similar mistakes in the future simply by selecting better, more intelligent leaders. However, this is not the case. The overwhelming majority of decisions in the Iraq War were made by highly intelligent, highly experienced leaders whose choices, often in consensus, seemed reasonable at the time they were made, but nonetheless added up over time to a failure to achieve our strategic objectives.”

The lessons of the Iraq War need to be learned by military leaders throughout the world, not just those in the US.

This admission is contained in a two-volume report that was issued by the US Army in 2019. The report was largely ignored but is finally in the news.

Iraq and Iran had a long history of rivalry. It reached its peak when the two countries went to war in 1980, a year after Ayatollah Khomeini took over the reins of power in Tehran. Iraq was governed by Saddam Hussain. He had a tough childhood, had never served in the military, and was a lawyer by training.

Concerned that a theocratic Iran may foment a rebellion among the Shia in Iraq, which accounted for a majority of the population, he attacked Iran. The bitter enemies fought for eight years. More than a million people were killed in the Iraq-Iran War but it had an inconclusive ending.

Iraq ran up a debt in billions and attacked Kuwait in 1990 to seize its oil field, precipitating the Gulf War. The US, concerned that after grabbing Kuwait’s oil fields, he will go after the Saudi Arabian oil fields, created a coalition of forces to drive him out.

The coalition was successful, despite the firing of SCUD missiles by Saddam into Saudi Arabia. I remember visiting Dhahran in Saudi Arabia in 1994 and seeing remnants of the Patriot missiles on display in a hotel lobby.

An uneasy calm returned to the region. It was shattered when 9/11 happened. In retaliation and self-defense, the US attacked the Taliban in Afghanistan, since they were found to be giving refuge to the al-Qaeda forces led by Osama bin Laden. The Taliban were deposed in a couple of months.

But the fear and anger that had been roused in the US was not quelled. Two years after 9/11, the US decided to hit Iraq with its full strength, claiming that Iraq was linked with al-Qaeda which had carried out the 9/11 attacks and further claiming that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction which posed an imminent danger to the West. At the time, 72 percent Americans supported the invasion.

On March 20, 2003, the US hit Iraq with bombs and missiles from all directions and invaded it with 130,000 troops. Unable to handle all this “Shock and Awe,” Baghdad fell in just 21 days.

In a symbolic gesture that reverberated around the globe, US troops toppled Saddam’s statue at Firdous Square in Baghdad on April 9.

The Iraq War damaged the reputation of the US throughout the globe, most notably in the Arab World. I was in Riyadh just a few months after the war. One uniformed officer asked me, “When is the cowboy going to get out of Iraq?” George W. Bush had come to symbolise the American cowboy in the Arab mind.

On May 1, President George W. Bush flew onto the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in a Lockheed S-3 Viking, 35 miles off the coast of San Diego. Under a “Mission Impossible” banner, he declared that major combat operations were over.

Unlike its military operations during the Gulf War of 1991, where a coalition of countries had joined hands with the US, this time the US was prepared to go in alone. As a formality, it sent General Colin Powell, the US Secretary of State, to the UN to prove that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and that those weapons posed a threat to the West. His speech did not convince anyone except the UK.

At home, large rallies were held in February 2003 in multiple cities to prevent the US from going to war. Along with hundreds of thousands of others, my wife and I participated in a large rally in San Francisco in front of City Hall to stop the war from taking place.

According to TIME magazine, the largest coordinated protests were held in February in several major cities of the world.

But Bush, working hand-in-glove with Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice, was not listening. Richard Clarke, the National Security Council’s counterterrorism coordinator was dumbfounded. He said that attacking Iraq when it had nothing to do with 9/11 was just as nonsensical as invading Mexico after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 12/7 in 1941.

As far back as August 2002, sensing an imminent invasion, Brent Scowcroft had published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal. He wrote presciently, “Our nation is presently engaged in a debate about whether to launch a war against Iraq. Leaks of various strategies for an attack on Iraq appear with regularity…[but] there is scant evidence to tie Saddam to terrorist organisations, and even less to the Sept 11 attacks. Indeed, Saddam’s goals have little in common with the terrorists who threaten us, and there is little incentive for him to make common cause with them…The United States could certainly defeat the Iraqi military and destroy Saddam’s regime. But it would not be a cakewalk. On the contrary, it undoubtedly would be very expensive – with serious consequences for the US and global economy –and could as well be bloody.”

The Iraq War damaged the reputation of the US throughout the globe, most notably in the Arab World. I was in Riyadh just a few months after the war. One uniformed officer asked me, “When is the cowboy going to get out of Iraq?” George W. Bush had come to symbolise the American cowboy in the Arab mind.

Two decades after the war started, the Iraq war is considered an unmitigated disaster in the US, both in terms of treasure and lives. The financial cost for the US has been estimated by experts at Harvard University at $3 trillion, sufficient to completely wipe out the US budget deficit for two years. Nearly 4,500 Americans died in the war and 32,000 were wounded.

Americans who fought in the war have been speaking against the war, saying they were sent into a country of which they neither knew the culture nor the terrain.

For Iraq, the devastation was beyond comprehension. Experts at Brown University estimate that more than 800,000 people died as a direct result of fighting. Of those, more than 335,000 were civilians. Worse, “another 21 million people have been displaced due to violence.” Today, just about everyone in Iraq has lost someone due to the US invasion.

Law and order have disappeared from a country that was once considered the safest Arab state. Chaos reigns on the streets. Two large cities – Mosul and Fallujah – are largely destroyed and damage is visible in almost every major city in central and northern Iraq.

Corruption is widespread, with Iraq ranking 157th among 180 countries in the corruption index developed by Transparency International. One third of the young are unemployed, according to the World Bank and the International Labor Organization.

George Piro, a young Lebanese American who worked in the FBI, stated that Saddam felt his biggest enemy was Iran. All his talk about his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) was designed to scare Iran. His biggest fear was that if Iran discovered how weak he was, they would invade southern Iraq and take it.

The ultimate mea culpa comes from Max Boot, one of the strongest advocates of the war. He writes, “I would never have supported military action had I known that he was not actually building weapons of mass destruction, but what I really wanted was to get rid of Iraq’s cruel dictator, not just his purported weapons program. One of the central arguments that I and other supporters of an invasion made was that regime change could trigger a broader democratic transformation in the Middle East. I now cringe when I read some of the articles I wrote at the time. ‘This could be the chance to right the scales, to establish the first Arab democracy, and to show the Arab people that America is as committed to freedom for them as we were for the people of Eastern Europe’.”

Like many analysts, he believed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. He also believed that democracy could be imposed by force. He forgot that democratic institutions did not exist in Iraq nor could they be created overnight. Iran had been ruled by dictators and absolute monarchs for decades. To add to its woes, the US demolished the two institutions that had kept Iraq together, the Baath Party and the Army.

Andrew Bacevich, Professor Emeritus at Boston University, notes that the Iraq War was “the acme of American military folly,” right after the Vietnam War. It was launched on the naïve assumption that American troops would be welcomed as liberators not just in Iraq but in the entire Arab world.

Bacevich writes: “Operation Iraqi Freedom instead produced a mournful legacy of death and destruction that destabilised the region. For a time, supporters of the war consoled themselves with the thought that the removal from power of the Iraqi tyrant Saddam Hussein had made the world a better place. Today, no amount of sophistry can sustain that claim.”

Melvyn Leffler, Professor Emeritus at Virginia University, concludes in his new book that the invasion was based on fear and hubris. Fear born out of the 9/11 attacks, the first on US soil since Pearl Harbor, and hubris, arising from its self-assessment of its preeminence in the globe.

Peter Bergen, in an opinion piece for CNN, recently interviewed George Piro, the FBI agent who interrogated Saddam Hussain after he had been captured. Bergen writes: “The dictator’s discussions with Piro confirmed that the Iraq War was America’s original sin during the dawn of the 21st century — a war fought under false assumptions, a conflict that killed thousands of American troops and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.”

George Piro, a young Lebanese American who worked in the FBI, stated that Saddam felt his biggest enemy was Iran. All his talk about his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) was designed to scare Iran. His biggest fear was that if Iran discovered how weak he was, they would invade southern Iraq and take it.

The reality is that whatever WMDs were in Iraq’s possession were destroyed by the UN inspectors. Saddam knew that Iraq, despite his boastful rhetoric, did not have the capacity to fight the US. He was neither a strategist or a tactician. Thus, he severely misjudged US intentions.

The US was convinced it could depose Saddam militarily in a matter of weeks and free the Iraqis from his despotic and tyrannical rule. After that, it felt that it would create a democratic dispensation which would make Iraq a beacon of freedom in the entire Arab world.

It did not realise that deposing Saddam and the Baath Party would open a Pandora’s Box. It did not heed the warning by Egypt’s foreign minister, who was the head of the Arab League, that invading Iraq “would open the gates of hell.”

Far from being a “slam dunk,” as one US leader had predicted it would be, the war turned out to be an impossible assignment, political as well as military. The US army history of the Iraq War, on page 653 of Volume 1, provides this stark assessment of how the situation deteriorated in a manner that no one in the US military had anticipated.

“From December 2003 to December 2006, the war in Iraq evolved from a relatively loose insurgency against the U.S.-led coalition into a horrific ethno-sectarian civil war that tore at the fabric of Iraqi society and threatened Iraq’s very existence as a unitary state. This 3-year period, which began with the false hope that Saddam Hussein’s capture in December 2003 would cause the insurgency to evaporate, quickly entered a demoralising stage caused by the April 2004 uprisings and the Abu Ghraib prison scandal. Had it not been for the response of the departing 1st Armored Division as an unplanned operational reserve, the coalition might well have suffered a strategic defeat along the lines of the 1968 Tet offensive in Vietnam.”

Once Saddam had been deposed, in-fighting broke out all over Iraq, with sinister sectarian and ethnic overtones, the likes of which Iraq had not seen in decades. Out of the carnage arose a new threat, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

It left al-Qaeda behind in the dust. An unknown man, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, rose to become the head of ISIS. He declared himself the caliph of the global Muslim nation or Ummah.

It wasn’t just the creation of ISIS that stunned the world. The US invasion had given birth to a new jihadist movement. The cruelty with which people were tortured and murdered, and their beheadings captured on videos, left the world stunned and bewildered. A depression set in. Iraqis began to reminisce and yearn for the days when Saddam ruled Iraq.

Iran was the only country left smiling after the Iraq War. Its main rival had been demolished by another rival, without it having to fire a single shot, lose a single soldier, or spend a dime.

Writing in TIME magazine, the authors of the official US report on the Iraq War say, “Iranian-backed militias, on the Iraqi payroll, now outnumber the Iraqi Army. The Ministry of Defense now includes officers and generals who are designated terrorists. Iranian aligned militias have captured state resources through political representation in Parliament and by controlling key posts in lucrative ministries. Iran’s influence now waxes in an uninterrupted arc from Tehran to the Mediterranean, traipsing across Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.”

Iraq’s largest trading partner is now Iran and the two countries have friendly ties. Their leaders have begun visiting each other.

President Bush did not accomplish his mission. He ended up accomplishing the opposite, letting Iran establish primacy over Iraq and the region. The Iraq War is yet another validation of the Law of Unintended Consequences which runs throughout history.

The US army’s history of the war ends with this damning conclusion: “In a way, it would be reassuring to believe that the mistakes the United States made in the Iraq War were the result of unintelligent leaders making poor decisions. If that were so, then the United States could be assured of avoiding similar mistakes in the future simply by selecting better, more intelligent leaders. However, this is not the case. The overwhelming majority of decisions in the Iraq War were made by highly intelligent, highly experienced leaders whose choices, often in consensus, seemed reasonable at the time they were made, but nonetheless added up over time to a failure to achieve our strategic objectives.”

The lessons of the Iraq War need to be learned by military leaders throughout the world, not just those in the US.