[Bukhari fell into an abandoned well in the gardens of Delhi Radio. On being pulled out, he was pronounced dead by five doctors in succession but was saved by the sixth, Dr Sagheer Hashmi of Karachi. For his recovery from the fall, he and Fielden went to a sanctuary in Almora, a hill station in Northern India.]

The accident had softened my disposition but the silent air of Almora and its meditating monks enchanted me into a state of ecstasy. I wanted to fall in love with everything around me. I felt as if “Everything is Him”.

Our host, Boshi Sen, was an eminent scientist of the time but a holy man at heart. He conducted his scientific experiments alongside his meditation. His English wife meditated with him in the deer park. Fielden lost himself to music; he would seek out his favourite records from Boshi Sen’s library and play them gently on the gramophone.

I felt as if I was treading lightly on a cloudy path to a nameless destination

I felt as if I was treading lightly on a cloudy path to a nameless destination. The cinders of radio’s frenzy and Delhi’s avarice died out. My heart was being drawn out almost magnetically towards Fielden. I thought to myself then - as I still do now - how I could possibly thank this stranger, a foreigner, an Englishman for his services. A person who tends to forget his good deeds can be only be thanked in silence with a heavy heart.

When I returned to Delhi, I became a devoted follower of Fielden. From the upkeep of the garden in his house to the supervision of his household staff, I undertook the care of all his personal chores. At this, some people called me a sycophant and whatnot, but, from my point of view, I couldn’t careless for their views in this delicate matter of love.

The majority in India condemned me for being Muslim yet Fielden’s right hand. The Brits suspected me to be the root cause of anarchy on account of corrupting “one of them” into befriending the dark-skinned. God knows this is a strange world: you are good if you hate someone but bad if you love.

The fact of the matter was the British had realised that they were gradually losing grip over India and that the Hindus and Muslims of India were beating them at their own game. The Brits no longer came here to write books, learn Urdu and Farsi, run the College of Fort William, compile dictionaries, etc. At the time, we had people hailing from the British equivalent of Lal Kurti rote learning their way through an exam to come here and govern the dark-skinned. These latest administrators hardly possessed the wisdom and grace to govern the Muslims who had ruled over the same land for eight hundred years before them.

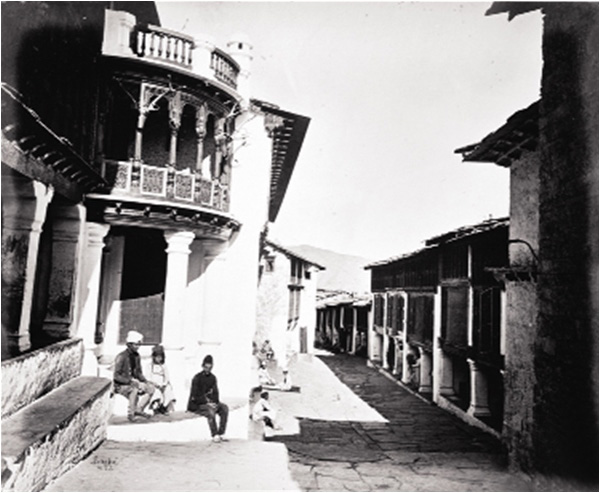

Recall the havelis in which the Muslim nobility used to live and compare them with the tin-roof bungalows of the suburban gentlemen built on tender by the Public Works Department along the main road. Imagine the delicacies enjoyed by the Muslim rulers and compare them with the hodgepodge the Brits here call dinner. Consider the hareer and deeba, atlas and zarbaft that our courtiers used to wear and compare them with the ruling Brits’ flannel trousers and hunter jackets, which hardly deserve to be called an attire.

Despite being the rulers, the Brits felt humiliated and this mental turmoil made them do stupid things

The British were overawed not only by this cultural comparison but also by the relative success of the native youth in the civil service examination once they were allowed to take it. Consequently, despite being the rulers, the Brits felt humiliated and this mental turmoil made them do stupid things.

The spirit of freedom displayed by the Muslims in 1857, the meeting of the Agha Khan-led Muslim delegation with Lord Minto in 1906, the ensuing acknowledgement of Muslims’ political significance, the establishment of the Muslim League, the enactment of Minto-Morley scheme, the entry of Muslims in the political arena upon the withdrawal of Bengal’s division, the capitulation of the Congress before Muslims during the First World War and the signing of the Lucknow Pact, the acceptance of Muslims’ demands in the Montagu-Chelmsford scheme, the enactment of the Rowlett Act for the fear of Maulana Muhammad Ali’s voice in the Khilafat Movement, the universal condemnation of the barbarism of martial law in Punjab, the return trips for the Round Table Conferences, the failure of the Simon Commission and the Nehru Report, the dazzling impact of Qauid-e-Azam’s Fourteen Points on Indian politics, the enactment of the Government of India Act in 1935, and Quaid-e-Azam becoming the president of Muslim League – the British could not forget all this. The spirit of freedom had taken root among Indians in general and among Indian Muslims in particular. Muslims could not accept the slavery of the British nor of a people they had ruled over for eight hundred years.

CID opened and read all our letters and listened to all our telephone calls

The Second World War seemed awfully imminent by 1935, and that prompted the British to set up radio in India so as to improve the government’s image. But unfortunately for the government, the reins of radio fell into the hands of a freedom-loving freethinker like Fielden, who in turn was helped by people motivated by the spirit of freedom instead of fear. Consequently, the government started keeping a close eye on us: we were interrogated and threatened with dismissal from our jobs all the time; CID opened and read all our letters and listened to all our telephone calls. In short, the government and the radio became a scourge for each other.

We could not help our yearning for liberty and the government could not help its urge to rule. Neither did they surrender, nor we. We did not have the heart to reduce ourselves to mere clay puppets. The government wanted the radio-wallahs to sing hymns of praise for the government but we had to take our microphone to the court of our countrymen, that is, our fellow slaves. The British were packing up to leave and therefore did not care. But we had to stay here; we had to live and die with our people.

But there was another difficulty for the Muslims, that is, we had to fight on two fronts: the British and the Congress. Here the trouble was that Fielden was inclined to favour Congress. Needless to say, Congress at the time had people who possessed several virtuous personal attributes regardless of their politics. We accompanied Fielden when he went to see Brother Asaf Ali (independent India’s first ambassador to the United States), Dr. Zakir Hussain (independent India’s first Muslim president), Pandat Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajgopal Achariya (the last governor-general of independent India) and Gandhi ji.

I fell utterly in love with Sarojini Naidu

I fell utterly in love with Sarojini Naidu: she enriched every gathering she joined. Maulan Abul Kalam Azad had come to Peshawar with Ali Brothers when his magazine Al-Hilal was still in print: he was delicate as a branch of jasmine and so fair as to be visible in darkness; arrha pajama with folds up to the middle of his calves, black patent leather pumps, white silken round turban with two to three folds and exquisite embroidery at the loose end, a small gold watch on the wrist, glasses with thin gold frame, but voice so loud and clear that his speech at the Muslim Club echoed in the Qissa Khwani Bazaar. Microphones were not yet in vogue and only people with true conviction could rule a public gathering. I remained in touch with Maulana when he was in Calcutta and later in Delhi as well.

I fell utterly in love with Sarojini Naidu: she enriched every gathering she joined. Maulan Abul Kalam Azad had come to Peshawar with Ali Brothers when his magazine Al-Hilal was still in print: he was delicate as a branch of jasmine and so fair as to be visible in darkness; arrha pajama with folds up to the middle of his calves, black patent leather pumps, white silken round turban with two to three folds and exquisite embroidery at the loose end, a small gold watch on the wrist, glasses with thin gold frame, but voice so loud and clear that his speech at the Muslim Club echoed in the Qissa Khwani Bazaar. Microphones were not yet in vogue and only people with true conviction could rule a public gathering. I remained in touch with Maulana when he was in Calcutta and later in Delhi as well.All these people were rebels against the government, so naturally the government did not like Fielden or I seeing these people. It was constantly looking for a way to separate Fielden and I but it could not think of a way to kill the snake without breaking the stick.

King George V passed away around that time. We were ordered to shut down all our programmes and broadcast only news and classical Western music. We were further instructed to read news without a hint of glee as if one of our own had died.

I appointed a worker to play Western music all day long and designated Agha Ashraf to read the news. Our studio apparatus had a knob that relayed the announcer’s voice when turned right and the programme of the music studio when turned left. Agha Ashraf was coughing acutely that day but sat down in that state to read the news of His Highness’ illness and passing away. He started off alright but after reading, “Five minutes before his demise, His Exalted Lordship said...” he had another fit of coughing and instantly turned the knob left to relay the music studio. There tabla player Baba Malang Khan was shouting this: “What bastard has taken away my hammer?”

The listeners heard this: “Five minutes before his demise, His Exalted Lordship said, ‘What bastard has taken away my hammer?’”

Nothing could be done about what happened, but the added misery was that the government’s furious inquiries only gave us fits of hysterical laughter.

Thankfully, [Government’s finance member] Sir James Grigg and [Viceroy] Lord Willingdon stepped in to dissipate the tension and ensure my continued stay in Delhi.