A casual observer of Pakistani culture would be fooled into believing that just a handful of languages are spoken the country – all of them being Indo-European, such as Urdu, Punjabi and Pashto. The country, however, has 74 living languages, including Hindko, Marwari and Sansi. A 2011 report published by UNESCO stated that 27 languages in the country are vulnerable, including Pakistan’s unique Dravidian language Brahui, which is mostly spoken in Balochistan.

As a fan of Tamil culture and literature, and armed with a decent understanding of the India’s great Dravidian language, this writer was keen to hear spoken Brahui, in an attempt to at least decode a few words. Unfortunately for such an exercise, the language that now – according to estimates – has two million speakers, has a lot of Baloch and Urdu loanwords which have replaced the original Dravidian words.

International linguists and historians have devoted a lot of time and energy into studying Brahui since the 19th century. According to the revised edition of the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, compiled by Thomas Burrow and Murray B. Emeneau, there are more than 300 cognates (words that have a common etymological origin) of Tamil and Brahui.

Franklin Southworth, American linguist and Professor Emeritus of South Asian Linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania is slightly more cautious when it comes to Brahui’s connections with a proto-Dravidian language. “Brahui shares just over 300 lexical items with the rest of Dravidian (and not all of these are unquestioned cognates), but the relationship of Brahui to Dravidian is not doubted by serious scholars these days,” Southworth wrote in a essay in a book titled The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity.

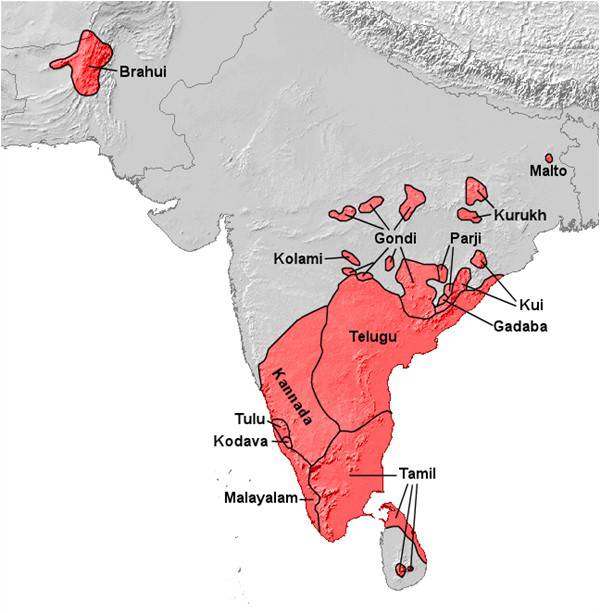

He adds: “Thus when we say that Tamil, Telugu, Toda, Kolami, Gondi, Malto, Brahui etc. are related, we are saying that we consider it proven that there was at some time in the past a single speech community (which we usually call Proto-Dravidian), and that each of these modern languages represents a historical continuation of some portion of that earlier community – since we know of no other circumstances which could give rise to the linguistic similarities among these languages.”

Conflicting histories

The very existence of Brahui is used as an excuse to justify conflicting histories. While the debate over the Aryan Invasion Theory does not look like it will end any time in the near future, some historians claim that Dravidians themselves invaded the Indian subcontinent and Brahui speakers are those who managed to stay behind in modern-day Balochistan and not move on to southern India. Others claim that there was a migration of Dravidian speakers to the area from southern India (or even what is now Maharashtra) in the 11th century.

Nazir Shakir Brahui, a historian and one of Pakistan’s most passionate Brahui activists, has written that the language originated in Balochistan and is the parent language of modern Dravidian and even Sindhi. The claim on the language of Sindh is not taken seriously by most linguists and historians.Many scholars do agree that Brahui is a northern Dravidian language and that Brahui speakers are indigenous to Balochistan, but it is difficult to understand the absence of related languages in this family in the vast stretch of land between the Pakistani province and southern India.

Russian scholar of Brahui

The greatest foreign scholar of Pakistan’s Dravidian language actually hailed from Russia. Mikhail Sergeyevich Andronov, a product of the now-defunct Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, took a great interest in South Asian languages, starting with Bengali before he moved on Dravidian languages.

Andronov studied at the University of Madras in the late 1950s and was one of the first European scholars to master Dravidian languages. In 1962 his first book titled Conversational Tamil and its Dialects was published in the Soviet Union. He would go on to publish Russian-Tamil, Russian-Malayalam and Russian-Kannada dictionaries, before writing books on the Malayalam language. While mastering Dravidian languages, Andronov also learned Brahui and published a Russian-Brahui dictionary.

His book A Grammar of the Brahui Language in Comparative Treatment is by far the most comprehensive look at Pakistan’s Dravidian language. Andronov was of the firm belief that Dravidian tribes migrated further towards India from 3,000 BC, but the Brahui-speakers stayed in modern-day Balochistan. He attributes subsequent foreign invasions as the reason that the Brahui diverged from other Dravidian languages.

At the time Andronov was working on his book titled The Brahui Language, he came across a small community of Brahui speakers who migrated to what was then the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic. The community managed to maintain their language in the Soviet Union. Andronov’s last book Dravidian Historical Lingusitics looks at the connections between Brahui and its sister languages including Tamil.

The future of Brahui in Pakistan

While Mikhail Andronov’s efforts were instrumental in helping to formalise the study of Brahui, the language’s future in its land of origin seems bleak. Songs in the language add to the country’s diverse musical heritage and there have been some televsion productions in Brahui, but it has almost no official patronage.

Native speakers of Brahui complain that the language is not amongst the regional languages in Pakistan’s Central Superior Services examination.There is a clear danger that the language may not survive the next few generations without official support in the country.

Saving ancient languages should be treated on par with protecting natural and historical heritage sites. Besides being an integral part of Pakistan’s diverse cultural heritage, Brahui can also serve as a link with southern India and become a much-needed bridge in a region where vested interests ensure that an environment of suspicion and mistrust prevails.

Ajay Kamalakaran is a writer based in Mumbai. His first work of fiction Globetrotting for Love and Other Stories from Sakhalin Island was published in 2017.

As a fan of Tamil culture and literature, and armed with a decent understanding of the India’s great Dravidian language, this writer was keen to hear spoken Brahui, in an attempt to at least decode a few words. Unfortunately for such an exercise, the language that now – according to estimates – has two million speakers, has a lot of Baloch and Urdu loanwords which have replaced the original Dravidian words.

International linguists and historians have devoted a lot of time and energy into studying Brahui since the 19th century. According to the revised edition of the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, compiled by Thomas Burrow and Murray B. Emeneau, there are more than 300 cognates (words that have a common etymological origin) of Tamil and Brahui.

Franklin Southworth, American linguist and Professor Emeritus of South Asian Linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania is slightly more cautious when it comes to Brahui’s connections with a proto-Dravidian language. “Brahui shares just over 300 lexical items with the rest of Dravidian (and not all of these are unquestioned cognates), but the relationship of Brahui to Dravidian is not doubted by serious scholars these days,” Southworth wrote in a essay in a book titled The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity.

He adds: “Thus when we say that Tamil, Telugu, Toda, Kolami, Gondi, Malto, Brahui etc. are related, we are saying that we consider it proven that there was at some time in the past a single speech community (which we usually call Proto-Dravidian), and that each of these modern languages represents a historical continuation of some portion of that earlier community – since we know of no other circumstances which could give rise to the linguistic similarities among these languages.”

Conflicting histories

The very existence of Brahui is used as an excuse to justify conflicting histories. While the debate over the Aryan Invasion Theory does not look like it will end any time in the near future, some historians claim that Dravidians themselves invaded the Indian subcontinent and Brahui speakers are those who managed to stay behind in modern-day Balochistan and not move on to southern India. Others claim that there was a migration of Dravidian speakers to the area from southern India (or even what is now Maharashtra) in the 11th century.

Nazir Shakir Brahui, a historian and one of Pakistan’s most passionate Brahui activists, has written that the language originated in Balochistan and is the parent language of modern Dravidian and even Sindhi. The claim on the language of Sindh is not taken seriously by most linguists and historians.Many scholars do agree that Brahui is a northern Dravidian language and that Brahui speakers are indigenous to Balochistan, but it is difficult to understand the absence of related languages in this family in the vast stretch of land between the Pakistani province and southern India.

Native speakers of Brahui complain that the language is not amongst the regional languages in Pakistan’s Central Superior Services examination. There is a clear danger that the language may not survive the next few generations without official support in the country

Russian scholar of Brahui

The greatest foreign scholar of Pakistan’s Dravidian language actually hailed from Russia. Mikhail Sergeyevich Andronov, a product of the now-defunct Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, took a great interest in South Asian languages, starting with Bengali before he moved on Dravidian languages.

Andronov studied at the University of Madras in the late 1950s and was one of the first European scholars to master Dravidian languages. In 1962 his first book titled Conversational Tamil and its Dialects was published in the Soviet Union. He would go on to publish Russian-Tamil, Russian-Malayalam and Russian-Kannada dictionaries, before writing books on the Malayalam language. While mastering Dravidian languages, Andronov also learned Brahui and published a Russian-Brahui dictionary.

His book A Grammar of the Brahui Language in Comparative Treatment is by far the most comprehensive look at Pakistan’s Dravidian language. Andronov was of the firm belief that Dravidian tribes migrated further towards India from 3,000 BC, but the Brahui-speakers stayed in modern-day Balochistan. He attributes subsequent foreign invasions as the reason that the Brahui diverged from other Dravidian languages.

At the time Andronov was working on his book titled The Brahui Language, he came across a small community of Brahui speakers who migrated to what was then the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic. The community managed to maintain their language in the Soviet Union. Andronov’s last book Dravidian Historical Lingusitics looks at the connections between Brahui and its sister languages including Tamil.

The future of Brahui in Pakistan

While Mikhail Andronov’s efforts were instrumental in helping to formalise the study of Brahui, the language’s future in its land of origin seems bleak. Songs in the language add to the country’s diverse musical heritage and there have been some televsion productions in Brahui, but it has almost no official patronage.

Native speakers of Brahui complain that the language is not amongst the regional languages in Pakistan’s Central Superior Services examination.There is a clear danger that the language may not survive the next few generations without official support in the country.

Saving ancient languages should be treated on par with protecting natural and historical heritage sites. Besides being an integral part of Pakistan’s diverse cultural heritage, Brahui can also serve as a link with southern India and become a much-needed bridge in a region where vested interests ensure that an environment of suspicion and mistrust prevails.

Ajay Kamalakaran is a writer based in Mumbai. His first work of fiction Globetrotting for Love and Other Stories from Sakhalin Island was published in 2017.