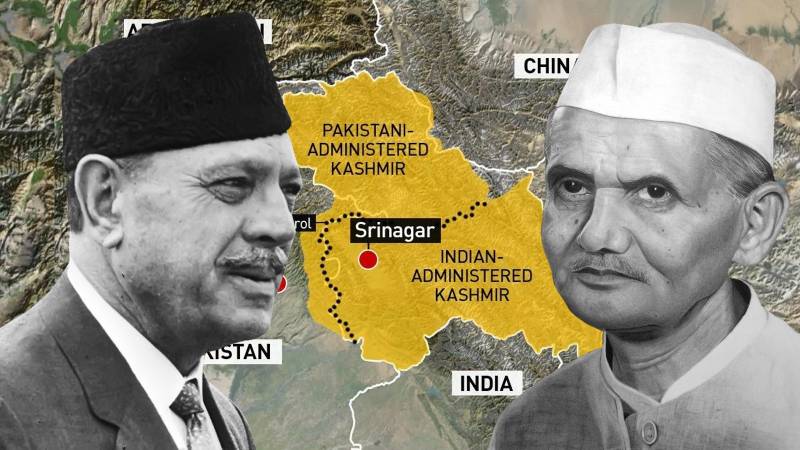

On August 5, 1965, Pakistan’s injection of guerrilla fighters into Indian Kashmir to instigate a rebellion led to a full-scale Indian attack on Lahore on September 6, a month later. That plunged the two countries into a full-scale war which ended abruptly on September 23, just 17 days later, when both countries accepted a UN ceasefire resolution. The short but intense conflict brought home the reality that neither country could prevail in a war over the other.

Pakistan’s President, Field Marshal Ayub Khan, visited the US, which was then led by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The two had similar personalities and clicked almost immediately. Ayub had hoped that he could convince the US to mediate Pakistan’s dispute over Kashmir with India. But, as Sir Morris James, who was the British High Commissioner in Pakistan at that time, writes in his memoirs, Pakistan Chronicle, in Johnson’s view, “Pakistan seemed to believe that America could exercise a great deal of influence on India regarding Kashmir, but this was quite wrong; he exhorted Ayub to get this idea out of his head and Kashmir out of his system.”

Much to Ayub’s surprise, Johnson said the US welcomed the Soviet Union’s offer to mediate in the dispute. The fact of the matter was that the US was getting more deeply involved in Vietnam and had no time to focus on Kashmir. The British, no longer the preeminent power that they once were, were equally uninterested in mediating on Kashmir and had adopted a hands-off policy. Both the US and the UK realized that there was no common ground between the Pakistani and Indian views on Kashmir. Both wanted to acquire all of Kashmir, which clearly was not an attainable objective.

The Soviets, led by Premier Alexei Kosygin, stepped into the fray, partly to contain their former ally, Communist China. Negotiations were held in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, from January 4-10, 1996.

All through the negotiations, which were held at several levels, between the foreign ministers of India and Pakistan, between Kosygin and the respective heads of governments of the two countries, and then bilaterally between the three heads of government, the Indians refused to budge on Kashmir.

The Tashkent Agreement that was signed on January 10, 1966 only made the briefest of references to it, and that too just in the preamble, where it stated that the two sides “had put forth their respective positions” on Kashmir.

It’s worth noting that in Pakistan, the agreement was referred to as a declaration, not an agreement. To further minimize its importance, when Ayub returned to Pakistan, he did not hold a press conference or give a speech on what he had signed in Tashkent. Farooq Bajwa, in his masterful account of the 1965 war and its aftermath, From Kutch to Tashkent, writes: “There is little doubt that the declaration was a diplomatic triumph for India and a defeat for Pakistan.”

There is no appetite for resolving the Kashmir imbroglio in the UN, not even in the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC), or among Pakistan’s closest friends in the Gulf, or in China. The world has moved on. No country wants to jeopardize its economic ties with India, which is emerging as a major world power.

Several points in the Tashkent Agreement were noteworthy. First, it said, “The Prime Minister of India and the President of Pakistan agree that both sides will exert all efforts to create good neighborly relations between India and Pakistan in accordance with the UN Charter. They reaffirm their obligation under the Charter not to have recourse to force and to settle their disputes through peaceful means.” This was to remain a pious hope. It never came to pass.

The second point noted that “all armed personnel of the two countries shall be withdrawn to the positions they held prior to 5 August, 1965.” That seemed to validate India’s position that Pakistan had plunged the two countries into war by injecting guerilla fighters into Indian Kashmir, a month prior to 6 September, which Pakistan had said was when the war began when it attacked Lahore.

Third, that “relations between India and Pakistan shall be based on the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of each other.” This point would be honored more in the breach than in the observance as years would pass.

Fourth, “both sides will discourage any propaganda directed against the other.” This too was honored more in the breach. The “propaganda directed against the other” continues to this day. Both countries continue to accuse the other of atrocious and deceitful conduct.

Fifth, “both Governments shall observe the Vienna Convention of 1961 on Diplomatic Intercourse.” Very little communication has taken place between the two governments via diplomatic channels.

Sixth, both sides “have agreed to consider measures toward the restoration of economic and trade relations, communications, as well as cultural exchanges between India and Pakistan.” To this day, very little trade has taken place between the two countries. There have been brief interludes where cricket teams have played each other on each other’s soil but most of the cricket matches have taken place in other countries.

And, seventh, both sides also agreed to sustain a dialogue with each other by holding meetings “both at the highest and at other levels on matters of direct concern to both countries.” Yes, a few meetings occurred when General Zia visited India to witness a cricket match, or when Prime Minister Vajpayee came to Lahore or when General Musharraf visited India, but they were few and far between.

Thus, the Tashkent Agreement failed to restore normalcy between the two countries. Because of a stroke of luck, Prime Minister Shastri of India died the day it was signed of a massive heart attack, going down in history as a peacemaker between the two countries. Field Marshal Ayub lost his political stature and much of his reputation in Pakistan, where the populace had been misled into thinking Pakistan had won the war.

His foreign minister, Z.A. Bhutto broke away from him and then turned on him, validating the dictum that no enemy is more dangerous than a former friend. In 1967, Bhutto created a new organization, the Pakistan Peoples Party, founded on the principles of what he called was an ideology of Islamic Socialism. After Pakistan’s defeat in the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, which resulted in the secession of East Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh, he was the President.

In that capacity, he travelled to India in 1972 and on July 2, signed the Simla Agreement with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Unlike the Tashkent Agreement where the Soviets acted as the intermediary, no one else was involved in the signing of the Simla Agreement. However, in many ways, it effusively echoed most of the points made in the Tashkent Agreement.

In the agreement, both countries stated that they had resolved to “put an end to the conflict and confrontation that have hitherto marred their relations and work for the promotion of a friendly and harmonious relationship and the establishment of durable peace in the subcontinent so that both countries may henceforth devote their resources and energies to the pressing task of advancing the welfare of their people.”

This was followed by a relentless barrage of platitudes: … the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations shall govern the relations between the two countries…the two countries are resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means…they will refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of each other…[they will not engage in] hostile propaganda each other.

The Simla Agreement went on to say that the two countries will take steps to “resume communications, postal, telegraphic, sea, land, including border posts, and air links, including over flights…Trade and cooperation in economic and other agreed fields will be resumed as far as possible…Exchange in the fields of science and culture will be promoted.”

Notably, the two countries agreed to respect the line of control resulting from the ceasefire of 17 December 1971 and “to refrain from the threat or the use of force in violation of this line.”

Once the Kashmir issue has been resolved, the two neighbors, who share a history that extends for millennia, can focus on peaceful trade and cultural cooperation, to the betterment of the lives of their citizens and those of the globe.

The only concrete result that followed from the Simla Agreement was the return of the prisoners of war from both sides, the vast majority of whom were on the Pakistani side.

In Pakistan, resentment continued to simmer on the issue of Kashmir. The leaders of the country continued to consider it the unfinished legacy of partition, and continued to argue that being a Muslim-majority state, it belonged in Pakistan.

In the spring of 1999, when the Pakistan army was commanded by General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan made yet another attempt to rouse the Muslim population in Indian Kashmir by attacking the outposts at Kargil. They scored some initial successes but eventually were met by the full fury of the Indian military. In a few months, the attack was repulsed and Pakistan forced to withdraw its forces.

Nothing changed on the ground. But the attack brought opprobrium on Pakistan. Even Pakistan’s all-weather friend, China, did not support the incursion in Kargil.

Today, nearly a quarter-century after Kargil, Kashmir remains an elusive issue and continues to bedevil relations between the two countries. Pakistan’s call for a plebiscite under the sponsorship of the UN has fallen on deaf ears. A prerequisite for such a plebiscite is that both countries withdraw their forces from Kashmir, which is something that neither side is willing to do.

There is no appetite for resolving the Kashmir imbroglio in the UN, not even in the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC), or among Pakistan’s closest friends in the Gulf, or in China. The world has moved on. No country wants to jeopardize its economic ties with India, which is emerging as a major world power.

The time has come for Pakistan to rethink the Kashmir issue. That conflict has caused Pakistan and India to spend billions of dollars on an expensive and increasingly dangerous arms race, which threatens not only the existence of the two countries but of much of the neighboring countries. That money would be much better spent on the human development of their peoples.

The economic welfare of nearly 2 billion people is at stake. In 1965, the population of Pakistan was just 100 million and that of India was 500 million, for a total of 600 million. Today, 1,828 million people reside in the subcontinent, consisting of 170 million in Bangladesh, 250 million in Pakistan and 1,408 million in India.

The only way to break the impasse over Kashmir is for Pakistan to accept the line of control as the international border. India will almost certainly accept it. The line of control has served as the de facto border since the first UN ceasefire went into effect on January 1, 1949. In the 74 years since, all other solutions that have been proposed have failed to get the agreement of both countries.

Kashmir has continued to be the quagmire. Pursuing the other solutions prolongs and intensifies the conflict. It also ensures that the Indo-Pakistan arms race will continue indefinitely, threatening the peace and stability of the world, and not just of the subcontinent.

Once the Kashmir issue has been resolved, the two neighbors, who share a history that extends for millennia, can focus on peaceful trade and cultural cooperation, to the betterment of the lives of their citizens and those of the globe. The only ones who will lose are the merchants of death, who make the weapons of mass destruction.