“We do not want to have two dead bodies coming out of our home,” they said. A young girl had been killed by her brother and the family was insisting on closing the matter. It was an open-and-shut case with the weapon of crime seized and the accused confessing rather boastfully. “Do you not love your daughter?” the bereaving mother was asked. Her tears gave away the answer, but she did not want to lose her son after losing her daughter, even though he was her killer.

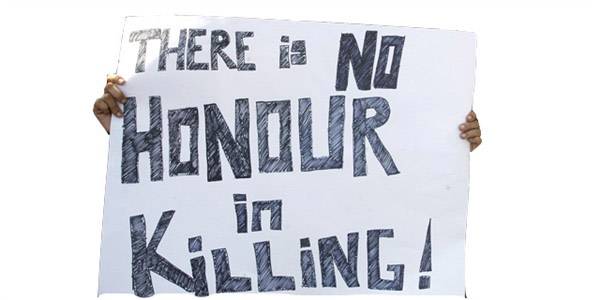

The story is painful but familiar, and often repeated. In the last five and half years, around 1,500 women and girls have been killed in the name of honour in the province of Punjab. The annual number is in the range of 300 to 375. This means a woman is killed in the name of honour almost every day. But such murders are not restricted to women. A large number of women are killed along with their life partners – the men they had chosen to spend their lives with, against the will and wishes of their family. The figure is however far lower – 88 in 2014 and 46 in 2015 as compared to 312 and 347 respectively for women.

Murder cases are contested vigorously in Pakistan. Many do end in compromises, as per Islamic law, but a large percentage of ordinary murder suspects spend years in prisons waiting for the victim’s family to pardon them. The pardon usually comes at a heavy price, often involving millions of rupees, and that too after lot of entreating. One in four cases end in death sentences, with appeals taking years.

But no such vigor is shown in honour killing cases. There have been only 79 convictions in such cases in the last five and half years – a tiny 5 percent of the total. The rest of the suspects were exonerated at various stages. In 2014, for example, 145 out of the total 390 registered cases were decided, and a majority of the accused were acquitted, either due to a compromise, or because the witnesses backed off. Only seven of the cases ended in convictions by trial courts. One of those seven cases was the murder of Farzana Parveen, which made headlines because it happened right outside the gates of Lahore High Court. Four members of her family were sentenced to death, only because her husband fought the case and refused to compromise.

Qandeel Baloch’s death has shaken us all, but even in that case, predictably, her father Muhammad Azeem was made the complainant. He is the eyewitness, and her mother Anwar Bibi is only a co-witness. Both her brothers are the accused. The investigation has led to the apprehension of a male cousin as well. The state, which initially left the matters of prosecution in the hands of her beleaguered parents, has now become involved with the addition of Section 311 of Pakistan Penal Code – a provision that is supposed to prevent a religious compromise or pardon.

But past record tells us that this would hardly be enough. The exit options for honour killers are too many. The courts have been blind to out-of-court settlements and pressures on the witnesses, over the years. In this case, even if there is no public pardoning, the parents will only have to change their statements and the accused would go free. How long they are going to hold ground can be anybody’s guess.

The state has promised new legislation, which would ensure that the accused in honour killings are not allowed the benefits of pardon under religious law, and judges would treat such cases as ‘fasad fil arz’, or social unrest. But those judges are still bound by the prevalent rules of evidence, which provide an opportunity of a legal exit for the accused. The state and the prosecution would be interested in a case as long as it is in the news, which is never more than few weeks.

Honour killings have been consistent in the last decade, despite the fact that the overall homicide rate is falling (with a marked decline after the resumption of death penalty executions). This menace cannot be stopped until we can protect women from their so-called protectors, and punish the perpetrators who are invariably closest relatives. This is not possible unless a separate, independent and empowered institutional structure is set up for the prosecution of such cases, just like there are special laws and institutions to deal with corruption, narcotics and terrorism. The state owes this to Qandeel Baloch and hundreds of other women.

The story is painful but familiar, and often repeated. In the last five and half years, around 1,500 women and girls have been killed in the name of honour in the province of Punjab. The annual number is in the range of 300 to 375. This means a woman is killed in the name of honour almost every day. But such murders are not restricted to women. A large number of women are killed along with their life partners – the men they had chosen to spend their lives with, against the will and wishes of their family. The figure is however far lower – 88 in 2014 and 46 in 2015 as compared to 312 and 347 respectively for women.

Murder cases are contested vigorously in Pakistan. Many do end in compromises, as per Islamic law, but a large percentage of ordinary murder suspects spend years in prisons waiting for the victim’s family to pardon them. The pardon usually comes at a heavy price, often involving millions of rupees, and that too after lot of entreating. One in four cases end in death sentences, with appeals taking years.

But no such vigor is shown in honour killing cases. There have been only 79 convictions in such cases in the last five and half years – a tiny 5 percent of the total. The rest of the suspects were exonerated at various stages. In 2014, for example, 145 out of the total 390 registered cases were decided, and a majority of the accused were acquitted, either due to a compromise, or because the witnesses backed off. Only seven of the cases ended in convictions by trial courts. One of those seven cases was the murder of Farzana Parveen, which made headlines because it happened right outside the gates of Lahore High Court. Four members of her family were sentenced to death, only because her husband fought the case and refused to compromise.

Judges are bound by prevalent rules of evidence

Qandeel Baloch’s death has shaken us all, but even in that case, predictably, her father Muhammad Azeem was made the complainant. He is the eyewitness, and her mother Anwar Bibi is only a co-witness. Both her brothers are the accused. The investigation has led to the apprehension of a male cousin as well. The state, which initially left the matters of prosecution in the hands of her beleaguered parents, has now become involved with the addition of Section 311 of Pakistan Penal Code – a provision that is supposed to prevent a religious compromise or pardon.

But past record tells us that this would hardly be enough. The exit options for honour killers are too many. The courts have been blind to out-of-court settlements and pressures on the witnesses, over the years. In this case, even if there is no public pardoning, the parents will only have to change their statements and the accused would go free. How long they are going to hold ground can be anybody’s guess.

The state has promised new legislation, which would ensure that the accused in honour killings are not allowed the benefits of pardon under religious law, and judges would treat such cases as ‘fasad fil arz’, or social unrest. But those judges are still bound by the prevalent rules of evidence, which provide an opportunity of a legal exit for the accused. The state and the prosecution would be interested in a case as long as it is in the news, which is never more than few weeks.

Honour killings have been consistent in the last decade, despite the fact that the overall homicide rate is falling (with a marked decline after the resumption of death penalty executions). This menace cannot be stopped until we can protect women from their so-called protectors, and punish the perpetrators who are invariably closest relatives. This is not possible unless a separate, independent and empowered institutional structure is set up for the prosecution of such cases, just like there are special laws and institutions to deal with corruption, narcotics and terrorism. The state owes this to Qandeel Baloch and hundreds of other women.