We all know about the mendacity of propagandists in Pakistan who have made heroes villains and villains heroes. It was via this monstrous apparatus that great men and women were slandered, their good names besmirched, their lives torn asunder by the brute force of repression. We have depended for too long on this regimen of lies for our information. And while we cannot bring Hassan Nasir, Mian Iftikharuddin, Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy, Ghaus Baksh Bizenjo and many other unsung heroes back to life, we can reiterate the truth for ourselves and hope that it finds an unbiased audience in this age of social media.

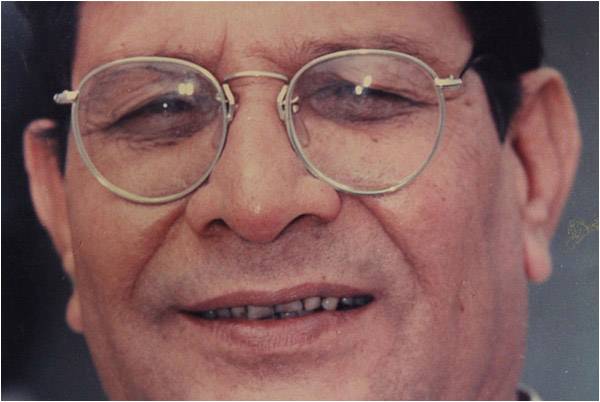

Mairaj Muhammad Khan was one such relentless crusader, whose life was dedicated to making that proverbial difference.

Born in 1938 in Qaimganj, United Provinces, Khan was a warrior by descent, and this General Ayub Khan ought to have known as should have his successors, Bhutto and Zia. The spirit of rebellion was a legacy to Mairaj Muhammad Khan from his Pathan ancestors who lost their fiefs but stood up to the might of the British Raj in 1857. It was not a loss that Khan ever lamented. “We became landless feudals. Successive generations had to earn their living. My grandfather turned to hikmat and passed on the profession to his son, my father. We lived, as we had done since the reign of Emperor Shahjehan, at Qaimganj in the United Provinces. That is where I grew up”. In between, Khan went to the Jamia Millia in Delhi where he remembered Dr Zakir Hussain as the most formative influence upon his young mind. Another was his autocratic father who was at pains to prevent him, a highborn Pathan, from fraternising with the sons of serfs “the rayyat” all around him. Perhaps it was the ghost of this overbearing father that haunted Mairaj Muhammad Khan in the guise of Pakistan’s successive dictators.

A year after the Partition, when he was ten, the family moved to Quetta. Khan was admitted to Sandeman School where he was asked to specify the reasons for the decline of the Mughal empire. He was quick to identify one cause above all, “the intolerance and bigotry of Aurangzeb in multi-religious India”. He related that experience thus: “I was given a severe beating. Worse than that, my teacher had turned on its head everything I had learnt in the liberal, secular milieu of the Jamia Millia. I refused to go back to school”. He matriculated nonetheless and as soon as that was done, fled to Karachi and to the civilised habitat of his older brother, Minhaj Barna, a crusading journalist.

At the Sindh Muslim College, Khan happened to take part in a debate. The oratory which cast a spell wherever he went, came naturally to Khan that day. He stole the show and the hearts and minds of the entire National Students Federation. He was handed over charge of one unit and was told to get on with his revolutionary duty. In those days, the NSF was planning a demonstration against President Eisenhower’s visit to Pakistan. The news leaked and led to Khan’s first acquaintance with jail. There were many more since then. But he emerged from the first one hardened in his socialist resolve.

One day, perhaps a historian will write about how the student movement of the 60s snowballed and culminated in General Ayub Khan’s downfall. For the purpose of this tribute, suffice it to say that Mairaj Muhammad Khan was central to that movement. He was among its brightest stars, its most fearless champions. For his pains, he was elected President of the NSF. And how could he have devoted any time to his studies? The truth is that he did not. Still, gifted as he was, he got through, and this was in the days when “getting through” meant something.

It came as a timely realisation to Khan that he could not remain a student leader all his life. He had to move on. In 1968, he helped form the Pakistan Peoples Party. “For many years, I mistrusted Bhutto. He was a feudal, I thought, who couldn’t possibly be an agent of change. In time, I became acquainted with his other side, the side that was the son of a deprived and spurned woman. He felt deeply for the poor, there is no doubt. But his basic instincts remained feudal. Perhaps that is why he was reluctant to set up a real organisation, tightly knit with grass roots. He wanted the movement to depend on his own myth.

“The first eye opener for me was back in 1968 when we were Mustafa Khar’s guests in Muzaffargarh, on the way to the Multan jalsa. Bhutto’s cronies accompanied us. There was Sadiq Qureshi, Rafi Munir and one or two others. In the evening, there was a mujra. Bhutto turned to Qureshi and said that his land reforms claims were all meant to appease the rabble, that he had no intention of implementing them. At the same time, he turned to me and gave me a broad wink. I left the room and stayed awake thinking about his duplicity. I could hear the sounds of revelry in the other room. Eventually, they all got up and went off with the woman. More than being morally offended, I was horrified that he could indulge himself like that on the eve of our biggest jalsa in Multan. The next morning, I told him how damaging it would be if word got out that he’d been up to no good. Bhutto shrugged his shoulders and changed the subject. This sort of thing caused me much anguish but we were so carried away by the momentum of events...”

Mairaj Muhammad Khan was Bhutto’s cats paw at all mammoth gatherings. No one could match Khan’s oratory. He was the greatest rabble-rouser of them all. But he was not to be remote controlled by Bhutto. At the Hala conference, for instance, Khan let rip a powerful attack on the vaderas in the Party. That Makhdum Talibul Maulah and Abdul Hamid Jatoi stormed out did not deter him. Neither did Mr Bhutto’s ire. “I went further. I told him that his attack on capitalists and traders was going to be counter-productive. They were our natural allies in progress, I said”. Bhutto would have none of that. They disagreed again when Khan says he told him that power must be transferred to Mujibur Rahman after his great electoral victory in East Pakistan. “Bhutto didn’t want that. I could feel it.

“When General Yahya came back from Dhaka and said that Mujib would be Prime Minister, Bhutto became frantic. He began to sow dissension among the anti-Bengali elements in the army. Eventually, at a jalsa in Lahore he said, ‘idhar ham, udhar tum’. Having said that, he returned to the Intercontinental hotel where I was waiting for him. ‘History will never forgive you’, I said. After the debacle, Yahya Khan invited Bhutto to parleys in Islamabad. I went with him. We went to Yahya’s residence and on our way to the room, Bhutto told me to be careful about protocol. When we entered the room, Yahya was sitting back in a chair wearing a pair of shorts and a vest. Nothing else. We began talking. Bhutto mentioned the Peoples Party. Yahya said, ‘Party? What party?’ His tone was insulting. I said, ‘What do you mean?’ Bhutto was very uncomfortable. Then Yahya stuck his tongue out at me, like an insolent child. It was ridiculous. Bhutto paled. We came down. That is when he made the declaration that if anything happened to him, I would be his heir.”

It was a declaration the mercurial Bhutto was quick to disregard. Khan had decided not to take part in the elections, on the misguided advice of his radical friends who had forecast the imminent demise of bourgeois parliamentary politics. For a while, Bhutto honoured his debt by conferring the ministry of labour and students affairs upon Khan. When in 1972, there was a murderous assault on protesting workers, Khan handed in his resignation. At the time, Bhutto denied responsibility and matters came to a head again when he ordered the army into Balochistan. Their parting of ways was final.

A year later, while leading a May Day demo, Khan was nearly killed with a blow to the head from his erstwhile partner’s henchmen. “I’d suffered long periods of torture, humiliation and solitary confinement at the hands of generals Ayub and Yahya. Bhutto’s jail was more distressing”. Mairaj Muhammad Khan must have been as close to a broken man at that time as he was ever likely to be. We also know that his head injury was near fatal and that he was allowed no medical attention by his captors.

Ironically, it was with General Zia’s coup that Khan was released. It is another matter that he was arrested again and released a little before Bhutto’s hanging. By then, his supporters in the PPP and outside, had formed the Qaumi Mahaz-e-Azadi, of which he was declared the leader. Mairaj Muhammad Khan of the relentless zeal helped form the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in 1981 and along with Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, spearheaded the subsequent movement to overthrow General Zia. It was after two years that he was released and that too, upon examination by jail doctors who suggested that he go abroad for treatment.

This, in the mid-80s, was Mairaj Muhammad Khan’s first visit to the West. By then, he was suffering fainting spells and loss of vision, thanks to the old head wound. Everywhere that he went, expatriate Pakistanis feted him, they took care of all his material needs. In the whole of London, there was not one doctor who presented him with a bill. Mairaj Muhammad Khan recovered from his blackouts but he had lost the vision of one eye for the rest of his life. I had asked him, after all that, how his wife and children had managed through it all. “I married in 1968. She and I were students together. She knew that I would be an unconventional husband. But I don’t think she could have imagined the kind of hardship she has had to endure.”

Ever the crusader, Khan allied with Benazir Bhutto and tried to get better sense to prevail. He even supported Nawaz Sharif for a while, thinking he was an agent of progress as a representative of the business classes. But Mairaj Muhammad Khan could not stomach the duplicity of 1990s politics, under constant pressure from the military. His acute frustration finally landed him a berth on Imran Khan’s Tehrik-e-Insaf. He quit the PTI in 2003, citing differences with Imran. Thereafter, Mairaj Muhammad Khan went back to his Communist roots and privately raged against the dying of the light. He died in Karachi last week.

Writing about him is at best a toting up of the small change of a heroic life. The real evaluation of Mairaj Muhammad Khan’s courage, integrity and contribution will come from the future, when a history of Pakistan’s liberation from its post-colonial hangovers is written.

Mairaj Muhammad Khan was one such relentless crusader, whose life was dedicated to making that proverbial difference.

Born in 1938 in Qaimganj, United Provinces, Khan was a warrior by descent, and this General Ayub Khan ought to have known as should have his successors, Bhutto and Zia. The spirit of rebellion was a legacy to Mairaj Muhammad Khan from his Pathan ancestors who lost their fiefs but stood up to the might of the British Raj in 1857. It was not a loss that Khan ever lamented. “We became landless feudals. Successive generations had to earn their living. My grandfather turned to hikmat and passed on the profession to his son, my father. We lived, as we had done since the reign of Emperor Shahjehan, at Qaimganj in the United Provinces. That is where I grew up”. In between, Khan went to the Jamia Millia in Delhi where he remembered Dr Zakir Hussain as the most formative influence upon his young mind. Another was his autocratic father who was at pains to prevent him, a highborn Pathan, from fraternising with the sons of serfs “the rayyat” all around him. Perhaps it was the ghost of this overbearing father that haunted Mairaj Muhammad Khan in the guise of Pakistan’s successive dictators.

A year after the Partition, when he was ten, the family moved to Quetta. Khan was admitted to Sandeman School where he was asked to specify the reasons for the decline of the Mughal empire. He was quick to identify one cause above all, “the intolerance and bigotry of Aurangzeb in multi-religious India”. He related that experience thus: “I was given a severe beating. Worse than that, my teacher had turned on its head everything I had learnt in the liberal, secular milieu of the Jamia Millia. I refused to go back to school”. He matriculated nonetheless and as soon as that was done, fled to Karachi and to the civilised habitat of his older brother, Minhaj Barna, a crusading journalist.

"Yahya Khan invited Bhutto to parleys in Islamabad. I went with him. We went to Yahya's residence and on our way to the room, Bhutto told me to be careful about protocol. When we entered the room, Yahya was sitting back in a chair wearing a pair of shorts and a vest. Nothing else. We began talking. Bhutto mentioned the Peoples Party. Yahya said, 'Party? What party?' His tone was insulting. I said, 'What do you mean?' Bhutto was very uncomfortable. Then Yahya stuck his tongue out at me, like an insolent child. It was ridiculous. Bhutto paled …"

At the Sindh Muslim College, Khan happened to take part in a debate. The oratory which cast a spell wherever he went, came naturally to Khan that day. He stole the show and the hearts and minds of the entire National Students Federation. He was handed over charge of one unit and was told to get on with his revolutionary duty. In those days, the NSF was planning a demonstration against President Eisenhower’s visit to Pakistan. The news leaked and led to Khan’s first acquaintance with jail. There were many more since then. But he emerged from the first one hardened in his socialist resolve.

One day, perhaps a historian will write about how the student movement of the 60s snowballed and culminated in General Ayub Khan’s downfall. For the purpose of this tribute, suffice it to say that Mairaj Muhammad Khan was central to that movement. He was among its brightest stars, its most fearless champions. For his pains, he was elected President of the NSF. And how could he have devoted any time to his studies? The truth is that he did not. Still, gifted as he was, he got through, and this was in the days when “getting through” meant something.

It came as a timely realisation to Khan that he could not remain a student leader all his life. He had to move on. In 1968, he helped form the Pakistan Peoples Party. “For many years, I mistrusted Bhutto. He was a feudal, I thought, who couldn’t possibly be an agent of change. In time, I became acquainted with his other side, the side that was the son of a deprived and spurned woman. He felt deeply for the poor, there is no doubt. But his basic instincts remained feudal. Perhaps that is why he was reluctant to set up a real organisation, tightly knit with grass roots. He wanted the movement to depend on his own myth.

“The first eye opener for me was back in 1968 when we were Mustafa Khar’s guests in Muzaffargarh, on the way to the Multan jalsa. Bhutto’s cronies accompanied us. There was Sadiq Qureshi, Rafi Munir and one or two others. In the evening, there was a mujra. Bhutto turned to Qureshi and said that his land reforms claims were all meant to appease the rabble, that he had no intention of implementing them. At the same time, he turned to me and gave me a broad wink. I left the room and stayed awake thinking about his duplicity. I could hear the sounds of revelry in the other room. Eventually, they all got up and went off with the woman. More than being morally offended, I was horrified that he could indulge himself like that on the eve of our biggest jalsa in Multan. The next morning, I told him how damaging it would be if word got out that he’d been up to no good. Bhutto shrugged his shoulders and changed the subject. This sort of thing caused me much anguish but we were so carried away by the momentum of events...”

Mairaj Muhammad Khan was Bhutto’s cats paw at all mammoth gatherings. No one could match Khan’s oratory. He was the greatest rabble-rouser of them all. But he was not to be remote controlled by Bhutto. At the Hala conference, for instance, Khan let rip a powerful attack on the vaderas in the Party. That Makhdum Talibul Maulah and Abdul Hamid Jatoi stormed out did not deter him. Neither did Mr Bhutto’s ire. “I went further. I told him that his attack on capitalists and traders was going to be counter-productive. They were our natural allies in progress, I said”. Bhutto would have none of that. They disagreed again when Khan says he told him that power must be transferred to Mujibur Rahman after his great electoral victory in East Pakistan. “Bhutto didn’t want that. I could feel it.

“When General Yahya came back from Dhaka and said that Mujib would be Prime Minister, Bhutto became frantic. He began to sow dissension among the anti-Bengali elements in the army. Eventually, at a jalsa in Lahore he said, ‘idhar ham, udhar tum’. Having said that, he returned to the Intercontinental hotel where I was waiting for him. ‘History will never forgive you’, I said. After the debacle, Yahya Khan invited Bhutto to parleys in Islamabad. I went with him. We went to Yahya’s residence and on our way to the room, Bhutto told me to be careful about protocol. When we entered the room, Yahya was sitting back in a chair wearing a pair of shorts and a vest. Nothing else. We began talking. Bhutto mentioned the Peoples Party. Yahya said, ‘Party? What party?’ His tone was insulting. I said, ‘What do you mean?’ Bhutto was very uncomfortable. Then Yahya stuck his tongue out at me, like an insolent child. It was ridiculous. Bhutto paled. We came down. That is when he made the declaration that if anything happened to him, I would be his heir.”

It was a declaration the mercurial Bhutto was quick to disregard. Khan had decided not to take part in the elections, on the misguided advice of his radical friends who had forecast the imminent demise of bourgeois parliamentary politics. For a while, Bhutto honoured his debt by conferring the ministry of labour and students affairs upon Khan. When in 1972, there was a murderous assault on protesting workers, Khan handed in his resignation. At the time, Bhutto denied responsibility and matters came to a head again when he ordered the army into Balochistan. Their parting of ways was final.

A year later, while leading a May Day demo, Khan was nearly killed with a blow to the head from his erstwhile partner’s henchmen. “I’d suffered long periods of torture, humiliation and solitary confinement at the hands of generals Ayub and Yahya. Bhutto’s jail was more distressing”. Mairaj Muhammad Khan must have been as close to a broken man at that time as he was ever likely to be. We also know that his head injury was near fatal and that he was allowed no medical attention by his captors.

Ironically, it was with General Zia’s coup that Khan was released. It is another matter that he was arrested again and released a little before Bhutto’s hanging. By then, his supporters in the PPP and outside, had formed the Qaumi Mahaz-e-Azadi, of which he was declared the leader. Mairaj Muhammad Khan of the relentless zeal helped form the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in 1981 and along with Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, spearheaded the subsequent movement to overthrow General Zia. It was after two years that he was released and that too, upon examination by jail doctors who suggested that he go abroad for treatment.

This, in the mid-80s, was Mairaj Muhammad Khan’s first visit to the West. By then, he was suffering fainting spells and loss of vision, thanks to the old head wound. Everywhere that he went, expatriate Pakistanis feted him, they took care of all his material needs. In the whole of London, there was not one doctor who presented him with a bill. Mairaj Muhammad Khan recovered from his blackouts but he had lost the vision of one eye for the rest of his life. I had asked him, after all that, how his wife and children had managed through it all. “I married in 1968. She and I were students together. She knew that I would be an unconventional husband. But I don’t think she could have imagined the kind of hardship she has had to endure.”

Ever the crusader, Khan allied with Benazir Bhutto and tried to get better sense to prevail. He even supported Nawaz Sharif for a while, thinking he was an agent of progress as a representative of the business classes. But Mairaj Muhammad Khan could not stomach the duplicity of 1990s politics, under constant pressure from the military. His acute frustration finally landed him a berth on Imran Khan’s Tehrik-e-Insaf. He quit the PTI in 2003, citing differences with Imran. Thereafter, Mairaj Muhammad Khan went back to his Communist roots and privately raged against the dying of the light. He died in Karachi last week.

Writing about him is at best a toting up of the small change of a heroic life. The real evaluation of Mairaj Muhammad Khan’s courage, integrity and contribution will come from the future, when a history of Pakistan’s liberation from its post-colonial hangovers is written.