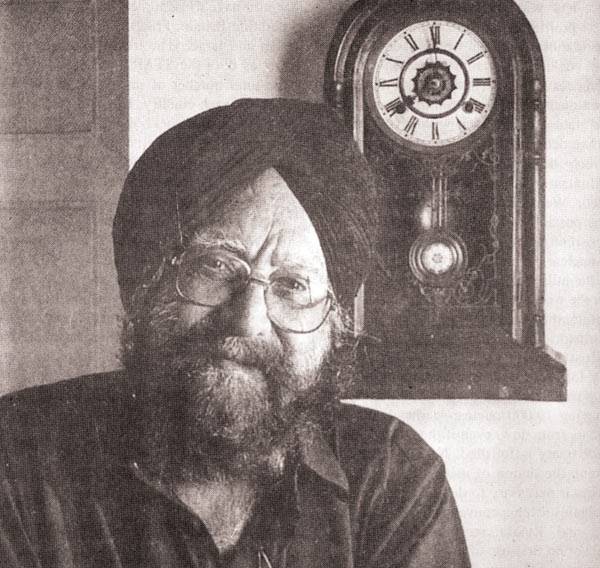

Khushwant Singh has done it again. The 84-year-old sardar has written yet another book on sexual fantasies called ‘In the company of Women’. Due later this month, this is Singh’s new novel after a nearly decade long hiatus. Though the tag of “dirty old man” is still firmly attached to his public persona, Singh suggests a more appropriate euphemism: “I am simply an old man with a dirty mind”.

Khushwant Singh’s irreverence is amply displayed in his writings, be it in his vast, erotic magnum opus on iris home city titled Delhi or in his syndicated columns that regularly make their appearance in the Indian and international press. I had the opportunity to sample the octogenarian’s wicked humour when I met him at his Sujan Singh Park apartment in New Delhi. “Look at this”, he said as he thrust a piece a paper at me. A newspaper clipping informed me that Singh had been adjudged “honest man of the year” by an Indian organisation for his sincerity of opinion and courage to stick to the truth. “What is even more hilarious is that they want to present me with a cheque for Rs 10 lakh and a gold watch”, chuckled Singh. “When the BBC people called me for comment I said that in a country of the blind the one-eyed is king!”. In saying this, the sardar was translating a famous Punjabi proverb, which is widely used both sides of the Indo-Pakistan border.

It therefore came as no surprise to me that this man of many talents, who has been a lawyer, bureaucrat, editor, academic, scholar and a member of the Rajya Sabha, hails from Lahore. “I studied at Government College, Lahore,from 1932-34 and then returned in’39 to practice law and stayed there till August 47’’, recalls Singh. His wedding in 1939 was attended by none other than Mr Jinnah whose Delhi residence sat across the road from the 1 Janpath house that belonged to Singh’s father. “Jinnah was mobbed by his admirers while myself and Kaval (his wife) were relegated to the sidelines”, he remembers. Even in 1947 when Singh had to leave Lahore due to the Partition riots he never thought that he was leaving for good. “I left my house in the keeping of my good friend, Manzur Qadir, convinced that this was a temporary move”. But for Singh, as well as countless others, Partition ended up dividing forever the soul of a nation. “Manzur would be more embarrassed than myself when greeting me at my Lawrence Road house whenever I used to visit Lahore”.

The bloodshed that Singh witnessed on both sides of the border together with personal accounts from other sources formed the basis of his tour de force Train to Pakistan, his moll successful novel to date, currently in its thirteenth reprint. ‘No work of fiction no matter which side it comes from has been written without tears of blood. You have Sadat Hassan Manto and Ghulam Abbas in Pakistan who wrote so movingly about Partition white in India countless writers acknowledged the pain of Partition and the deep scars it left”.

For Singh the attachment to Lahore is fast fading. “Most of my old friends have passed away and each time I return to Lahore it gets less and less recognisable”. Still old loves die hard which is precisely the reason why Singh dedicated his first collection of short stories, published in England in the 50s, to his friends Asghari and Manzur Qadir and “to my beloved city of Lahore”. It was in Lahore that Singh began writing as part of a literary circle that used to meet once a week at his house. “We would each of us read out a poem or a short story written by ourselves But it so happened that only my work was picked up by the publishers”.

Singh received rave reviews for his short stories and by the 50s was being talked of in the same company of distinguished Indian writers as R K Narayan. Although he continued to write steadily through the years, his spirit of wanderlust kept him constantly on the move. “I couldn’t get away from the feeling that the job I held at that time could be done by just about anybody”. Which is why he gave up promising careers in the External Service and UNESCO that saw him posted in London and Paris, amongst other places, to return home. This he did only to face the disapproval of his father. It was therefore enormously gratifying for Khushwant Singh that his “father lived long enough to see me being wined and dined by ambassadors and statesmen from all over the world”.

[quote]Though the tag of “dirty old man” is still firmly attached to his public persona, Singh suggests a more appropriate euphemism: “I am simply an old man with a dirty mind ... l think l have taken good care not to be revered. The five joke books that I have written get me more royalty than anything serious that I have written so far”[/quote]

Born in a tiny village called Hadali near Khushab, south of the Salt Range, Singh returned to his ancestral village on a visit to Pakistan eight years ago. “I got special permission to visit the place and when I got there the entire village had turned out to welcome me. I was so overcome with emotion that I couldn’t speak. Many old people remembered my family and a man even showed me a postcard my father had sent him”. The hero’s welcome that awaited him in Pakistan was not without reason for Singh continued to nurse a soft spot for his native land even in times of war. “During the Bangladesh war I was in Dacca and had the opportunity to meet some Pakistani POWs. f inquired if there were any from my native village because I knew l a lot of them had joined the army, Six men were brought before me and I talked to them and took down their parents’ names and wrote to them informing them that their sons were safe”.

As for his new book Singh declares that it is “pure fantasy...the ideas of an old man of what he would have liked to have done as a young man but didn’t”. Singh is convinced that the book will come under strenuous attack from his critics. “I arouse a certain amount of envy because I sell so well. Three editions of Delhi were sold out before the book even appeared on the market because of all the hype that surrounded it”. Singh is convinced that his new novel will perpetuate the image of the “dirty old man”. When I asked him how he came to be branded as such, pat came the reply: “It’s envy. It happened after the publication of Delhi which outraged a lot of people who hadn’t even read it”.

He then recounted an incident following the publication of that novel which involved his travelling to Hyderabad at the invitation of a Muslim organisation to deliver a lecture on the Quran to. non-Muslims. “Half the audience turned out to be Muslim, of which twenty or so young men got up and started shouting that I not be allowed to speak for I had portrayed Muslim men in my novel as being vulgar and cruel”, Singh recalls. He asked the protestors if any of them had read the book and it turned out that not a single one had done so. “One of the men critiqued me far using a picture of a naked woman holding out a cup of wine to the Mughal ruler, Shah Jehan: I corrected him saying that the ruler was not Shah Jehan but Nadir Shah and that these incidents appear in his biography”, he said with a chuckle.

Yet another incident of irreverence involved the Nobel prize winner Rabindranath Tagore. “In Shilong I said to somebody that I thought Tagore was vastly over-rated. By the time I got to Calcutta a huge crowd had gathered there and the Bengal Assembly as well as the Rajya Sabha passed a resolution against me. They said how dare I criticise a man they worshiped. I told them that instead of worshipping him they should read him!” When I asked Singh if he had ever wished to be revered in the same way as Tagore, Singh replied with a hearty laugh, “I think I have taken good care not to be revered. The five joke books that I have written get me more royalty than anything serious that I have written so far.”

Getting away with just about anything has become Khushwant Singh’s hallmark. Despite being a proclaimed agnostic, in April of this year he was awarded the Nishan-e-Khalsa, the highest honour to be given by the Sikh community. “I was awarded a doctorate by the Guru Nanak University despite the fact that the chancellor expressed his disagreement with my views”. And the fact remains that Khushwant Singh’s contribution to literature and history is unparalleled. He has written what is probably the best known account of Sikh history called the History of the Sikhs, a publication that spans four volumes and which took him as many years to complete.

“I always went out of my way to efface the impression regarding the inveterate hatred between Sikhs and Muslims which is why I routed the hook through the Aligarh Muslim University”, says Singh. “A fact not known to many is that the chief hymn singers at the Golden Temple in Amritsar were Muslim right up to Partition”. So committed was he to producing the definitive work on Sikh history that the book ends with the Latin phrase Opus Exegii - “my life’s work is done”. This was followed by a biography of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and another book that documents the Call of the Sikh kingdom.

But Khushwant Singh’s work seems far from over. When he isn’t poking fun at Indian politicians, he has been quoted as saying “We’ve had so many donkeys as PM” he is receiving a constant stream of visitors at his apartment. For the best-selling author of over 80 books and two weekly columns syndicated in over 40 English publications as well as the translator of such Urdu masterpieces as Um-rao Jan and Iqbal’s Shikwa and Jawaab-e-Shikwa, it’s not for nothing that Khushwant Singh is regarded as Delhi’s best known living monument.

Khushwant Singh’s irreverence is amply displayed in his writings, be it in his vast, erotic magnum opus on iris home city titled Delhi or in his syndicated columns that regularly make their appearance in the Indian and international press. I had the opportunity to sample the octogenarian’s wicked humour when I met him at his Sujan Singh Park apartment in New Delhi. “Look at this”, he said as he thrust a piece a paper at me. A newspaper clipping informed me that Singh had been adjudged “honest man of the year” by an Indian organisation for his sincerity of opinion and courage to stick to the truth. “What is even more hilarious is that they want to present me with a cheque for Rs 10 lakh and a gold watch”, chuckled Singh. “When the BBC people called me for comment I said that in a country of the blind the one-eyed is king!”. In saying this, the sardar was translating a famous Punjabi proverb, which is widely used both sides of the Indo-Pakistan border.

It therefore came as no surprise to me that this man of many talents, who has been a lawyer, bureaucrat, editor, academic, scholar and a member of the Rajya Sabha, hails from Lahore. “I studied at Government College, Lahore,from 1932-34 and then returned in’39 to practice law and stayed there till August 47’’, recalls Singh. His wedding in 1939 was attended by none other than Mr Jinnah whose Delhi residence sat across the road from the 1 Janpath house that belonged to Singh’s father. “Jinnah was mobbed by his admirers while myself and Kaval (his wife) were relegated to the sidelines”, he remembers. Even in 1947 when Singh had to leave Lahore due to the Partition riots he never thought that he was leaving for good. “I left my house in the keeping of my good friend, Manzur Qadir, convinced that this was a temporary move”. But for Singh, as well as countless others, Partition ended up dividing forever the soul of a nation. “Manzur would be more embarrassed than myself when greeting me at my Lawrence Road house whenever I used to visit Lahore”.

The bloodshed that Singh witnessed on both sides of the border together with personal accounts from other sources formed the basis of his tour de force Train to Pakistan, his moll successful novel to date, currently in its thirteenth reprint. ‘No work of fiction no matter which side it comes from has been written without tears of blood. You have Sadat Hassan Manto and Ghulam Abbas in Pakistan who wrote so movingly about Partition white in India countless writers acknowledged the pain of Partition and the deep scars it left”.

For Singh the attachment to Lahore is fast fading. “Most of my old friends have passed away and each time I return to Lahore it gets less and less recognisable”. Still old loves die hard which is precisely the reason why Singh dedicated his first collection of short stories, published in England in the 50s, to his friends Asghari and Manzur Qadir and “to my beloved city of Lahore”. It was in Lahore that Singh began writing as part of a literary circle that used to meet once a week at his house. “We would each of us read out a poem or a short story written by ourselves But it so happened that only my work was picked up by the publishers”.

Singh received rave reviews for his short stories and by the 50s was being talked of in the same company of distinguished Indian writers as R K Narayan. Although he continued to write steadily through the years, his spirit of wanderlust kept him constantly on the move. “I couldn’t get away from the feeling that the job I held at that time could be done by just about anybody”. Which is why he gave up promising careers in the External Service and UNESCO that saw him posted in London and Paris, amongst other places, to return home. This he did only to face the disapproval of his father. It was therefore enormously gratifying for Khushwant Singh that his “father lived long enough to see me being wined and dined by ambassadors and statesmen from all over the world”.

[quote]Though the tag of “dirty old man” is still firmly attached to his public persona, Singh suggests a more appropriate euphemism: “I am simply an old man with a dirty mind ... l think l have taken good care not to be revered. The five joke books that I have written get me more royalty than anything serious that I have written so far”[/quote]

Born in a tiny village called Hadali near Khushab, south of the Salt Range, Singh returned to his ancestral village on a visit to Pakistan eight years ago. “I got special permission to visit the place and when I got there the entire village had turned out to welcome me. I was so overcome with emotion that I couldn’t speak. Many old people remembered my family and a man even showed me a postcard my father had sent him”. The hero’s welcome that awaited him in Pakistan was not without reason for Singh continued to nurse a soft spot for his native land even in times of war. “During the Bangladesh war I was in Dacca and had the opportunity to meet some Pakistani POWs. f inquired if there were any from my native village because I knew l a lot of them had joined the army, Six men were brought before me and I talked to them and took down their parents’ names and wrote to them informing them that their sons were safe”.

As for his new book Singh declares that it is “pure fantasy...the ideas of an old man of what he would have liked to have done as a young man but didn’t”. Singh is convinced that the book will come under strenuous attack from his critics. “I arouse a certain amount of envy because I sell so well. Three editions of Delhi were sold out before the book even appeared on the market because of all the hype that surrounded it”. Singh is convinced that his new novel will perpetuate the image of the “dirty old man”. When I asked him how he came to be branded as such, pat came the reply: “It’s envy. It happened after the publication of Delhi which outraged a lot of people who hadn’t even read it”.

He then recounted an incident following the publication of that novel which involved his travelling to Hyderabad at the invitation of a Muslim organisation to deliver a lecture on the Quran to. non-Muslims. “Half the audience turned out to be Muslim, of which twenty or so young men got up and started shouting that I not be allowed to speak for I had portrayed Muslim men in my novel as being vulgar and cruel”, Singh recalls. He asked the protestors if any of them had read the book and it turned out that not a single one had done so. “One of the men critiqued me far using a picture of a naked woman holding out a cup of wine to the Mughal ruler, Shah Jehan: I corrected him saying that the ruler was not Shah Jehan but Nadir Shah and that these incidents appear in his biography”, he said with a chuckle.

Yet another incident of irreverence involved the Nobel prize winner Rabindranath Tagore. “In Shilong I said to somebody that I thought Tagore was vastly over-rated. By the time I got to Calcutta a huge crowd had gathered there and the Bengal Assembly as well as the Rajya Sabha passed a resolution against me. They said how dare I criticise a man they worshiped. I told them that instead of worshipping him they should read him!” When I asked Singh if he had ever wished to be revered in the same way as Tagore, Singh replied with a hearty laugh, “I think I have taken good care not to be revered. The five joke books that I have written get me more royalty than anything serious that I have written so far.”

Getting away with just about anything has become Khushwant Singh’s hallmark. Despite being a proclaimed agnostic, in April of this year he was awarded the Nishan-e-Khalsa, the highest honour to be given by the Sikh community. “I was awarded a doctorate by the Guru Nanak University despite the fact that the chancellor expressed his disagreement with my views”. And the fact remains that Khushwant Singh’s contribution to literature and history is unparalleled. He has written what is probably the best known account of Sikh history called the History of the Sikhs, a publication that spans four volumes and which took him as many years to complete.

“I always went out of my way to efface the impression regarding the inveterate hatred between Sikhs and Muslims which is why I routed the hook through the Aligarh Muslim University”, says Singh. “A fact not known to many is that the chief hymn singers at the Golden Temple in Amritsar were Muslim right up to Partition”. So committed was he to producing the definitive work on Sikh history that the book ends with the Latin phrase Opus Exegii - “my life’s work is done”. This was followed by a biography of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and another book that documents the Call of the Sikh kingdom.

But Khushwant Singh’s work seems far from over. When he isn’t poking fun at Indian politicians, he has been quoted as saying “We’ve had so many donkeys as PM” he is receiving a constant stream of visitors at his apartment. For the best-selling author of over 80 books and two weekly columns syndicated in over 40 English publications as well as the translator of such Urdu masterpieces as Um-rao Jan and Iqbal’s Shikwa and Jawaab-e-Shikwa, it’s not for nothing that Khushwant Singh is regarded as Delhi’s best known living monument.