Sara Suleri Goodyear, nee Sara Suleri, one of four daughters born to Pakistan Times editor and journalist Z. A. Suleri, died last week in her home in the coastal city of Bellingham, US.

While I did not know her well personally, she was an iconic figure in my chosen profession: American academia.

The first Pakistani woman – and feminist – scholar, writer and professor of English to become a tenured member of the prestigious Yale University faculty, Sara was an inspiration to those handful of us like myself who followed in her path and became Pakistani American academics pursuing careers at universities in the USA.

I recall her generosity in letting me sit in on some of her lectures at a class in Third World Literature she was teaching at Yale, when I was struggling with my PhD dissertation-writing phase at Tufts. This was the mid 1980s and I was impressed there was even such a course being offered, and that too at Yale, a bastion of conservatism dedicated to upholding the canon of English Literature. Clearly, Sara was forging new paths leading to the creation of programs of study in postcolonial literature and theory within departments of English in US universities. Like the other students in her class, I too was mesmerised by her intensity of focus and brilliance of mind, that came across to us with resounding clarity in each carefully crafted sentence she uttered.

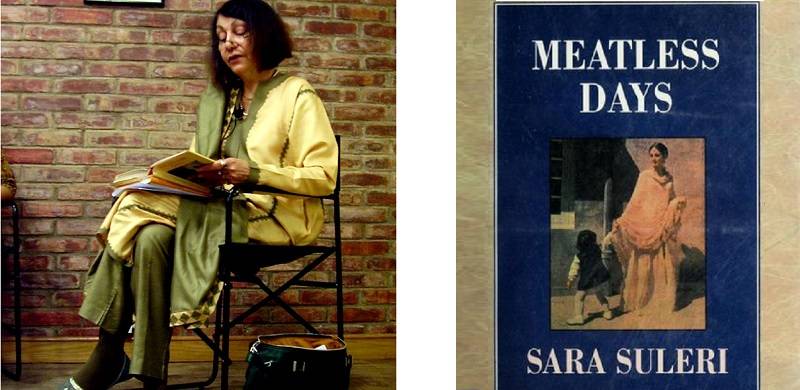

A few years later, after I’d finished my PhD and started my tenure track position at Montclair State University in NJ, Sara published a memoir entitled Meatless Days, set largely in my birth city of Lahore, where she and I both attended Kinnaird College for Women, a half decade apart.

I remember being startled by her choice to publish a memoir instead of a staid scholarly work first, on her path to tenure, and that too at such an elite university. But that was her gift: an unconventional boldness that was part of her originality of vision, which certainly inspired me to challenge academic strictures and structures as well.

Her memoir Meatless Days proved groundbreaking in both style and substance in a genre that was only just beginning to be taken seriously as an object of scholarly study. Sara contributed enormously to that project by instantiating brilliantly and with both humour and pathos, in jewel-like syntax and utterly original turns of the phrase — the feminist insight of the personal as political. In the process, she created a new vocabulary, theorising an emergent interdisciplinary field combining insights and methodologies of literary criticism with those of Women’s Studies, that came to be called postcolonial feminist cultural studies.

A few short years later, her first (and sadly, last) book of scholarly criticism was published, The Rhetoric of English India (1992).

Once again, her book generated intense interest and garnered much praise for the originality of insights and selections of texts it focused on. For those of us who had only major male scholars like Edward Said to guide us on our path to becoming postcolonial critics and scholars, Sara’s book and essays such as the now iconic Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition — helped us push our own thinking further, to examine the gender blind spots in the work of many postcolonial theorists; further, to treat with skepticism what Sara would have called out as a “triumphalism” of categories of identity.

A restless deconstructive spirit animated Sara’s work and persona, urging on those who admired her always original interventions, the need to be constantly self reflexive and skeptical of all manner of pieties.

But despite all the significant achievements and contributions to knowledge production that the world shall rightfully honour her for, to me the memory that shall always stand out is the one that binds us to the unforgettable undergraduate alma mater we shared. I remember how I watched her in dazed admiration on the KC stage as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, in a production of the stage play about the youngest and supposedly only surviving daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, by Marcelle Maurette, directed by the inimitable Perin Cooper. I came to see the play when I was still in school at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, and was instantly smitten by Sara who was so beautifully regal in the role, opposite Rubina Saigol, yet another amazing actor and budding feminist who – unlike Sara and me – stayed on in Pakistan and became one of its fiercest feminist activists and scholars, fighting for women’s rights, especially in the field of education. Rubina also, sadly, passed away not too long ago. And now, with Sara’s departure from our earthly firmament, I am reminded of the necessity —nay urgency – of keeping the memory of these pioneering feminist academics, artists, activists alive.

Sara Suleri was, and remains, as inspirational a figure as the woman she once portrayed on stage: courageous and graceful in the face of life’s manifold challenges.

While I did not know her well personally, she was an iconic figure in my chosen profession: American academia.

The first Pakistani woman – and feminist – scholar, writer and professor of English to become a tenured member of the prestigious Yale University faculty, Sara was an inspiration to those handful of us like myself who followed in her path and became Pakistani American academics pursuing careers at universities in the USA.

I recall her generosity in letting me sit in on some of her lectures at a class in Third World Literature she was teaching at Yale, when I was struggling with my PhD dissertation-writing phase at Tufts. This was the mid 1980s and I was impressed there was even such a course being offered, and that too at Yale, a bastion of conservatism dedicated to upholding the canon of English Literature. Clearly, Sara was forging new paths leading to the creation of programs of study in postcolonial literature and theory within departments of English in US universities. Like the other students in her class, I too was mesmerised by her intensity of focus and brilliance of mind, that came across to us with resounding clarity in each carefully crafted sentence she uttered.

Her memoir Meatless Days proved groundbreaking in both style and substance in a genre that was only just beginning to be taken seriously as an object of scholarly study

A few years later, after I’d finished my PhD and started my tenure track position at Montclair State University in NJ, Sara published a memoir entitled Meatless Days, set largely in my birth city of Lahore, where she and I both attended Kinnaird College for Women, a half decade apart.

I remember being startled by her choice to publish a memoir instead of a staid scholarly work first, on her path to tenure, and that too at such an elite university. But that was her gift: an unconventional boldness that was part of her originality of vision, which certainly inspired me to challenge academic strictures and structures as well.

Her memoir Meatless Days proved groundbreaking in both style and substance in a genre that was only just beginning to be taken seriously as an object of scholarly study. Sara contributed enormously to that project by instantiating brilliantly and with both humour and pathos, in jewel-like syntax and utterly original turns of the phrase — the feminist insight of the personal as political. In the process, she created a new vocabulary, theorising an emergent interdisciplinary field combining insights and methodologies of literary criticism with those of Women’s Studies, that came to be called postcolonial feminist cultural studies.

A few short years later, her first (and sadly, last) book of scholarly criticism was published, The Rhetoric of English India (1992).

Once again, her book generated intense interest and garnered much praise for the originality of insights and selections of texts it focused on. For those of us who had only major male scholars like Edward Said to guide us on our path to becoming postcolonial critics and scholars, Sara’s book and essays such as the now iconic Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition — helped us push our own thinking further, to examine the gender blind spots in the work of many postcolonial theorists; further, to treat with skepticism what Sara would have called out as a “triumphalism” of categories of identity.

A restless deconstructive spirit animated Sara’s work and persona, urging on those who admired her always original interventions, the need to be constantly self reflexive and skeptical of all manner of pieties.

But despite all the significant achievements and contributions to knowledge production that the world shall rightfully honour her for, to me the memory that shall always stand out is the one that binds us to the unforgettable undergraduate alma mater we shared. I remember how I watched her in dazed admiration on the KC stage as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, in a production of the stage play about the youngest and supposedly only surviving daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, by Marcelle Maurette, directed by the inimitable Perin Cooper. I came to see the play when I was still in school at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, and was instantly smitten by Sara who was so beautifully regal in the role, opposite Rubina Saigol, yet another amazing actor and budding feminist who – unlike Sara and me – stayed on in Pakistan and became one of its fiercest feminist activists and scholars, fighting for women’s rights, especially in the field of education. Rubina also, sadly, passed away not too long ago. And now, with Sara’s departure from our earthly firmament, I am reminded of the necessity —nay urgency – of keeping the memory of these pioneering feminist academics, artists, activists alive.

Sara Suleri was, and remains, as inspirational a figure as the woman she once portrayed on stage: courageous and graceful in the face of life’s manifold challenges.