Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for the first part

At some time that term a family friend, a retired senior army officer who was once my father’s students in PMA, told my parents about a Pakistani family in Rome who had a marriageable daughter. The father worked at a high position in the international bureaucracy in Rome and he invited me for the winter holidays. I bought the ticket and after such scares as leaving my passport in the underground and then retrieving it just in the nick of the time and getting scowled at by my first Paki-basher—my first and only encounter with racism (unless, as Fahad tells me, I am too obtuse to notice subtle instances of racism)—I boarded the plane for Rome. Outside the customs the father and the elder brother of the girl stood to welcome me and I went with them to their flat in a posh area of the city. When the door of the flat opened a boy jumped up with rolling eyes and uttering strange sounds. I understood at once that he was mentally challenged. This was Javeed (not his real name), the youngest son of the family. Then I met the mother and away from the grown-ups stood two girls. The eldest was obviously the girl I was sent out to meet because the younger one was only a school girl. I noticed that she was good-looking and stood confidently though without a smile of welcome or encouragement of any kind. I also noticed that her head was covered with a scarf (abaya) as is much commoner now than it was in the 1980s.

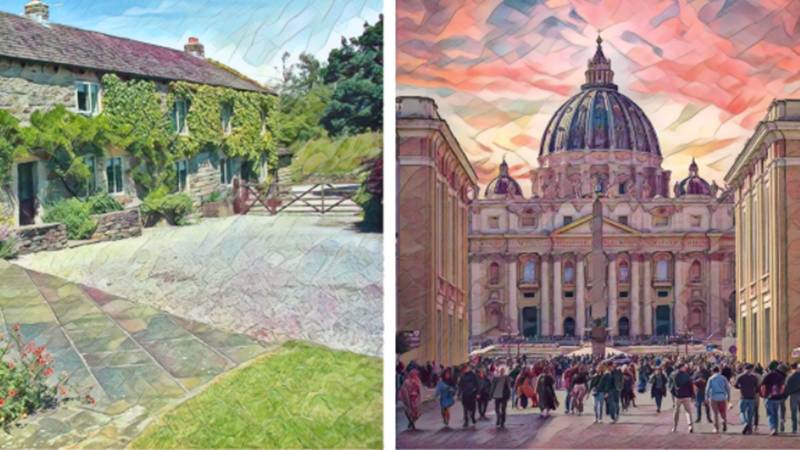

I went to bed confused and bit depressed at the sight of Javeed. I was prone to morbid thoughts those days and this was not the kind of family I expected. I thought that such things as Javeed’s condition could run in the family; in the children too. At breakfast, however, I cheered up because the mother was so warm and natural – like my own mother. The father was also very friendly. Apparently, she herself had been given the duty of showing me the sights of Rome so that morning she took me by bus to St Peter’s Cathedral. Despite her Muslim form of dressing, she studied in the University of Kent at Canterbury where too she wore her headscarf. From this I judged that she was far too strict in her interpretation of religion than I would find congenial. She was also quite aloof and did not talk much to me. But this could be because she felt it inappropriate to put herself out too much and appear forward. She handled Javeed very affectionately saying: “piano, piano, Javeed” when he became too excited. I gave her full marks for such sensitive behaviour.

I loved the city of Rome. It was a city of ancient, majestic buildings, beautiful statues and imposing churches. Above all I loved St Peter’s Cathedral where I gazed with rapture at the painted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. I was much moved by the fact that I was seeing the place where Christianity had established itself. I saw the traditional Swiss guards with huge pikes on the gates of the Vatican Palace where the Pope lived. I even went on Christmas morning to St Peters when the Pope, it is said, blesses the earth in his Urbi et Orbi address. One day she took me to the fountain where one throws a coin in and makes a wish. I threw a coin in and made no wish, which is what I told her when she asked me. She smiled and we talked a bit more than usual that day.

The day she really thawed towards me was when we took Javeed, who had been more than usually difficult, for a ride on the swings. Somehow, we abandoned the childish ones and chose a roller coaster in which Javeed sat with me while she herself waited for us below. As the machine lurched up and came down fast, Javeed, in common with others, shouted but he was really terrified. I pulled him close and comforted him saying “piano, piano Javeed” as his sister did. He was in a desperate condition with the whites of the eyes rolling and his face contorted in terror. But then the roller coaster stopped and he rushed out to his waiting sister who hugged him close. Javeed made a gesture to her indicating that his heart beat fast and that I had saved him from some terrible disaster. It was then that she gave me a very warm smile—a smile which made her face radiant and very friendly-- and murmured “thank you” several times.

However, we said nothing about the reason I had come to Rome. I did not know how to broach the subject as I had decided that we would not be congenial marriage partners. She did not even obliquely refer to this subject which, I rightly concluded, did not become her maidenly dignity. She might have guessed my intentions though. Also, when her father asked me whether I wanted to work for the United Nations, I told him plainly that I wanted to serve in a university. They were a decent family and did not probe me too deeply. I am afraid I did not tell them anything clearly which I really should have. I still feel that I did wrong for trespassing on their hospitality for nearly twenty days and then not even mentioning anything about the marriage.

"I left the dining hall and came on the deck. The sky was dark and a cold wind lashed me in the face. The sea was stormy and I felt it reflected the storm in my mind. I came down feeling worse than before"

However, on the 31st of December 1981 I left Rome by train for Berlin where my childhood friend Hasan Ali Raza (resigned as captain), lived with his wife. He was a squash instructor having been Army No 1 in Pakistan. It was a glorious winter day and we crossed Italy and then the breath-taking Italian Alps. Just as the sun’s last rays gilded the white snow-capped heights, we crossed the border and entered Austria. Then the train went dark and when the winter sun rose again, we were near Berlin. It was on the first of January 1981 that I got off the train in Berlin. It was freezing cold and there was snow on the ground. I rang Ali and he instructed me to get to his apartment. I went by taxi and met Ali, his wife, and two small sons. They welcomed me and were very hospitable to me for the next week or so that I stayed with them. Ali used to teach squash while I used to swim in the sports centre. Ali himself wondered how I could do that since everyone was stark naked in the swimming pool and he had never met any Pakistani or Indian visitor who felt comfortable swimming like that. Indeed, he himself felt so uncomfortable that he eschewed swimming altogether. I said it did not bother me except that one had to keep one’s eyes downcast:

“Why?” asked Ali mockingly. “Because you would be staring with an open mouth as our desi (South Asians) people do at the lovely young girls. And if one does that the Germans would call us barbarians.”

“No Ali,” I replied, “the real problem is not to offend one’s own aesthetic sensibilities because most people are elderly, out of shape and far from easy on the eyes. As for the kind of nubile nymphets you have in your fantasies, they can hardly afford this place and the sauna is especially expensive. Also, those who go to such places, like myself, get sophisticated enough not to ogle them even if they are there.”

“Stop teaching me as if I was born yesterday,” replied Ali in a huff while I guffawed. He then added that it was hardly possible to keep one’s eyes downcast like a shy maiden all the time so I shrugged my shoulders and set off for another swim. Moreover, I went all over West Berlin alone on the excellent subway system. Berlin had excellent restaurants and Ali took me to some of them. He also took me to a place where the hostesses were completely in the nude on the assumption that I would like the experience. Two equine ladies, rather Olympian in proportions, came and sat down next to us. I looked at Ali and he looked at me. We knew we had to get away as soon as possible.

“Did you know we would be entertained by horses? What is stopping us from leaving now?” I whispered to Ali in Urdu.

“I have paid for the horses,” he replied! And a Pathan has to eat what he had paid for. Aren’t you a Pathan by race?” he said.

“Pathan or no Pathan I’m leaving,” I replied.

By now the horses were getting close to us so we got up rather quickly with Ali thanking them in German: “Danke, danke schön.” And we made for the exit.

When this visit ended, I left by train which took me across Europe at night and reached Holland in the morning. That beautiful, flat country with guilders which looked like the fake currency, the kind of money one used in the game called “trade” I used to play, appeared charming in the morning sun. At Rotterdam I caught a ferry and it started on its way across the North Sea to England. In the ferry I again became morbidly introspective which led to the usual state of anxiety and depression I had faced before having embarked for Rome. I left the dining hall and came on the deck. The sky was dark and a cold wind lashed me in the face. The sea was stormy and I felt it reflected the storm in my mind. I came down feeling worse than before and watched the movie Black Beauty. When I got down in blistery England, I was definitely feeling bad. I tried to read PG Wodehouse but got bored. London came and the buildings appeared like Blake’s “satanic mills” to me. Then came the coach ride to Sheffield.

In Sheffield, I, Sheridan and Graham (a South African black youth) had taken a windy little house. I had got the smallest room and told the others I would wash the dishes since I could not cook. But I found myself unable to sleep and I hardly ever got a proper, hot meal to eat. This was nobody’s fault since people ate at all times and nobody set the table or bothered about a hot meal. Very soon I desperately wanted to go back to Marie Loo’s house. I was so desperate that, even though I had paid for the term, I left my money and went. Nobody objected since they could see that my health was deteriorating.

In Marie Loo’s house I got proper meals all right but my health became worse and worse. Soon I started losing sleep and my heart started sinking. I felt so desolate and lonely that I had to go to the doctor. The British health system was free, efficient and caring. But the doctor could not help me much. The sleeping pills he gave me made very little difference. I dreaded the nights; I dreaded the lonely evenings. I felt as if my heart would sink and I felt apprehensive about things which could never happen. I had had brief and mild attacks of anxiety ever since I was fourteen which I have mentioned earlier. But I had always been in the supportive atmosphere of my family or the army so I had never felt lonely. The loneliness in England brought about this crisis. Sometimes my heart palpitated wildly and I imagined I would have a heart attack. This was probably some sort of panic attack but this I did not know then. Every evening, when I lay down in bed, I would listen to Lorna Doone, Dr Jekyl and Mr Hyde and a drama I had bought on tape. This was my major entertainment. The other entertainments were reading books and, of course, meeting friends.

My friends were very helpful indeed. Sometimes one of them would come in the evening to play scrabble with me. Even Billie and Richard took turns at giving me company. Jill used to come also though she never visited males in their rooms on principle. One day, when I was feeling particularly ill, she sat down on my bed and prayed for me. Indeed, Jill worked assiduously to sooth my forehead which throbbed with a headache. And then she did something very unexpected: she bent down and gave me a peck on the forehead. It was a very chaste and caring kiss which only a nun could have given—but I was deeply touched. I patted her thatch of auburn hair and murmured “thank you Jill.” She said she would pray for me and went out though it was late at night. I knew that the serial killer was still at large and normally she never went out so late in the evenings, so I gallantly offered to walk her down to her digs but she resolutely declined my offer. She had never visited my room so late so I was worried but she rang me when she reached safe and sound and I was much relieved.

These visits did not work and one day I decided to leave England. I went to the British Council office and everybody was so helpful, understanding and cooperative that I was surprised and deeply moved. To begin with, Heywood visited me in my room assuring me that I would be given leave. I decided to finish my essays because I was sure I would not be able to send them from Pakistan. At the next seminar Dr Mackerness gave me a warm smile. Dr Bentley made some very consoling remarks and my class fellows assured me I would be back soon. Within a week the British Council representative took me by train to London and even to the house of my cousin, Commander Sultan Ahmad Khan. His wife, however, thought I was staging a drama to go back to Pakistan. This hurt me a lot and I made it clear to her that my ticket would have been paid for even if I had been in perfect health. She then thought that I might have been thrown out of the course.

(to be continued)