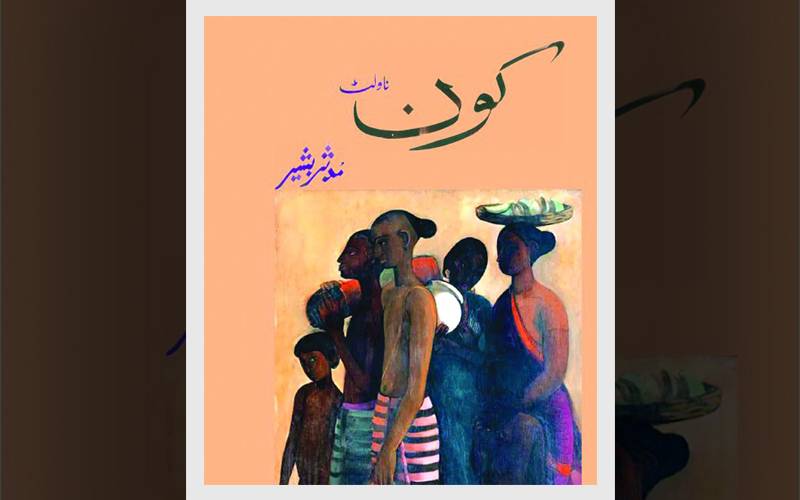

The Vancouver-based annual Dhahan Prize for Punjabi literature recently announced three winners, with the first prize going to Jatinder Singh Haans from Aloona Tola in Indian Punjab, while the finalist award went to two authors: Gurdev Singh from Rupana, India, and Lahore-based Punjabi historian and writer, Mudassar Bashir, for his 2018 novelette titled Kon (Who).

Bashir’s earlier work has focused heavily on history, a concern that dominates his literary imagination in Kon as well. The novelette is structured around the earnest, frenzied efforts of its protagonist, Sarmad, to realise his dream to become a “hero,” as he ploughs through script after script in the studio’s old archive, in search of the ultimate character, the defining role that will kickstart his career. Sarmad confines himself to a rehearsal room, with glimmering lights whose shadows dance on the mirrored walls, transporting him through a jumble of hallucinatory journeys into the past, across space and contexts. His sole companion is what he refers to as “the best director any actor could ask for” – a mirror. The novel’s realism blurs into the magical as the mirror becomes a powerful character in the novel, Sarmad’s key interlocutor as he navigates the cultural and social landscape of historical South Asia. The Mirror instructs, mocks, encourages and seduces Sarmad in equal measure, and the interplay between the two functions as the canvas on which the author grafts his reading of our colonial and postcolonial history.

Several themes that have preoccupied progressive writing in Punjabi are foregrounded through the cast of characters that the budding actor Sarmad resurrects from the dusts of time. The first character from the yellowing screenplays he is drawn to is that of “Ditta Saini,” who is identified as a mazdoor (worker). The Mirror mediates Sarmad’s exploration of the character, his material conditions and sense of political identity, exhorting the budding thespian to bring thundering conviction to his rendition of Saini by adopting a deep baritone reverberating off the surfaces of Sarmad’s cramped rehearsal room. “I am Ditta Saini!” booms the erstwhile timid Sarmad, emerging shaken and somewhat dishevelled from his foray into this very demanding character. He gathers himself and moves on to the next script, exclaiming how this character is “too difficult” for him. The mirror’s sneering laughter in response sounds its symbolic function in the novel. The mirror is a reflection of both self and society, and in the role of “director” raises critical questions regarding the relationship between art, society and politics – Can art transform the Self? Does a character’s consciousness shape an actor’s subjectivity? Sarmad’s discomfort with the character of Ditta Saini circles around these questions, pointing to the tension between the protagonist’s privileged class position and the destitution of the working class character he wishes to embody. A discussion of the radical theatrical methods of Augusto Boal and Bertolt Brecht between Sarmad and Joseph precedes this episode, setting the stage for Bashir’s exploration of the complex interplay between art and politics.

The appearance of Ditta Saini, along with the character of the humble clerk that follows, also creates an opening for exploring the entwined history of progressivism and film in South Asia. The anti-colonial, Left-wing politics of the All India Progressive Writers’ Movement (AIPWA) and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) decisively shaped aesthetic choices in the decades leading up to and succeeding the decolonisation of the subcontinent in 1947. AIPWA and IPTA provided the budding film industries of both Pakistan and India with many noted artists, ushering in the forms of Socialist Realism into popular culture with iconic films such as Jago Hua Sawera (1959) and Zarqa (1969). The character of Ditta Saini is a vestige of this progressive past, a reminder of both the power of the worker as political subject, and of South Asian cinema’s origins in a cultural politics that foregrounded the lives, experiences and desires of the exploited class. In a sense, Sarmad’s discomfort with portraying the character, and his inability to identify with Ditta Saini signals the distance that divides art and progressive politics today, allowing the author to make a critical comment on the current, degenerative state of mainstream film and popular culture in Pakistan.

However, Kon’s reflection on contemporary art is rooted in the historical context of colonialism, in particular focusing on its crippling impact on regional languages and literary cultures. The privileging of Urdu and English in the formation of a middle-class dominated national culture is critiqued through the characters of Khan Sahab and Deputy Nazir Ahmed, and the identity crisis that plagues the postcolonial is represented in the stark visual of two marble statues that flank the entrance to Sarmad’s rehearsal studio, one of William Shakespeare and the other, of Agha Hashar Kashmiri. Shakespeare’s monumental presence frames the continuing dominance of colonial culture, reinforced by the immortalised depiction of an Indian writer most celebrated for his vernacular adaptations of Shakespeare. As the novel progresses, and Sarmad encounters more and more characters in his scripts, we are confronted with the dissident Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, and the sacred duo of Sikhism, Guru Nanak Dev and Bhai Mardana, whose emergence signals a direct contrast with Shakespeare and Agha Hashar Kashmiri, prompting the reader to reflect on these marginalised cultural strands in postcolonial Pakistan.

However, what is striking is the dearth of female characters, an oversight that unfortunately dominates the male-centric vision of much literature produced by contemporary Punjabi writing in Pakistan. While caste and class divides inform the thematic palette of the novel, the important role of gendered histories and women’s agency in art and folk culture could have been explored through female characters drawn from the Punjabi literary formation. Further, the question of genre also arises. Kon reads much more like a play, with long passages of dialogue between characters. While this structure cleverly mirrors the motif of theatre and acting being explored in the text, the choice of the novelette form is somewhat unclear, as the narrative thrust and rich description typical of the form is missing in certain parts. Nevertheless, Bashir’s Kon makes for an enjoyable read, offering a lively exploration of North India’s cultural history, highlighting the complex interplay of language politics, subalternised tradition and the colonial encounter with its an array of fantastical characters drawn from the past.

Bashir’s earlier work has focused heavily on history, a concern that dominates his literary imagination in Kon as well. The novelette is structured around the earnest, frenzied efforts of its protagonist, Sarmad, to realise his dream to become a “hero,” as he ploughs through script after script in the studio’s old archive, in search of the ultimate character, the defining role that will kickstart his career. Sarmad confines himself to a rehearsal room, with glimmering lights whose shadows dance on the mirrored walls, transporting him through a jumble of hallucinatory journeys into the past, across space and contexts. His sole companion is what he refers to as “the best director any actor could ask for” – a mirror. The novel’s realism blurs into the magical as the mirror becomes a powerful character in the novel, Sarmad’s key interlocutor as he navigates the cultural and social landscape of historical South Asia. The Mirror instructs, mocks, encourages and seduces Sarmad in equal measure, and the interplay between the two functions as the canvas on which the author grafts his reading of our colonial and postcolonial history.

Several themes that have preoccupied progressive writing in Punjabi are foregrounded through the cast of characters that the budding actor Sarmad resurrects from the dusts of time. The first character from the yellowing screenplays he is drawn to is that of “Ditta Saini,” who is identified as a mazdoor (worker). The Mirror mediates Sarmad’s exploration of the character, his material conditions and sense of political identity, exhorting the budding thespian to bring thundering conviction to his rendition of Saini by adopting a deep baritone reverberating off the surfaces of Sarmad’s cramped rehearsal room. “I am Ditta Saini!” booms the erstwhile timid Sarmad, emerging shaken and somewhat dishevelled from his foray into this very demanding character. He gathers himself and moves on to the next script, exclaiming how this character is “too difficult” for him. The mirror’s sneering laughter in response sounds its symbolic function in the novel. The mirror is a reflection of both self and society, and in the role of “director” raises critical questions regarding the relationship between art, society and politics – Can art transform the Self? Does a character’s consciousness shape an actor’s subjectivity? Sarmad’s discomfort with the character of Ditta Saini circles around these questions, pointing to the tension between the protagonist’s privileged class position and the destitution of the working class character he wishes to embody. A discussion of the radical theatrical methods of Augusto Boal and Bertolt Brecht between Sarmad and Joseph precedes this episode, setting the stage for Bashir’s exploration of the complex interplay between art and politics.

The appearance of Ditta Saini, along with the character of the humble clerk that follows, also creates an opening for exploring the entwined history of progressivism and film in South Asia. The anti-colonial, Left-wing politics of the All India Progressive Writers’ Movement (AIPWA) and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) decisively shaped aesthetic choices in the decades leading up to and succeeding the decolonisation of the subcontinent in 1947. AIPWA and IPTA provided the budding film industries of both Pakistan and India with many noted artists, ushering in the forms of Socialist Realism into popular culture with iconic films such as Jago Hua Sawera (1959) and Zarqa (1969). The character of Ditta Saini is a vestige of this progressive past, a reminder of both the power of the worker as political subject, and of South Asian cinema’s origins in a cultural politics that foregrounded the lives, experiences and desires of the exploited class. In a sense, Sarmad’s discomfort with portraying the character, and his inability to identify with Ditta Saini signals the distance that divides art and progressive politics today, allowing the author to make a critical comment on the current, degenerative state of mainstream film and popular culture in Pakistan.

However, Kon’s reflection on contemporary art is rooted in the historical context of colonialism, in particular focusing on its crippling impact on regional languages and literary cultures. The privileging of Urdu and English in the formation of a middle-class dominated national culture is critiqued through the characters of Khan Sahab and Deputy Nazir Ahmed, and the identity crisis that plagues the postcolonial is represented in the stark visual of two marble statues that flank the entrance to Sarmad’s rehearsal studio, one of William Shakespeare and the other, of Agha Hashar Kashmiri. Shakespeare’s monumental presence frames the continuing dominance of colonial culture, reinforced by the immortalised depiction of an Indian writer most celebrated for his vernacular adaptations of Shakespeare. As the novel progresses, and Sarmad encounters more and more characters in his scripts, we are confronted with the dissident Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, and the sacred duo of Sikhism, Guru Nanak Dev and Bhai Mardana, whose emergence signals a direct contrast with Shakespeare and Agha Hashar Kashmiri, prompting the reader to reflect on these marginalised cultural strands in postcolonial Pakistan.

However, what is striking is the dearth of female characters, an oversight that unfortunately dominates the male-centric vision of much literature produced by contemporary Punjabi writing in Pakistan. While caste and class divides inform the thematic palette of the novel, the important role of gendered histories and women’s agency in art and folk culture could have been explored through female characters drawn from the Punjabi literary formation. Further, the question of genre also arises. Kon reads much more like a play, with long passages of dialogue between characters. While this structure cleverly mirrors the motif of theatre and acting being explored in the text, the choice of the novelette form is somewhat unclear, as the narrative thrust and rich description typical of the form is missing in certain parts. Nevertheless, Bashir’s Kon makes for an enjoyable read, offering a lively exploration of North India’s cultural history, highlighting the complex interplay of language politics, subalternised tradition and the colonial encounter with its an array of fantastical characters drawn from the past.