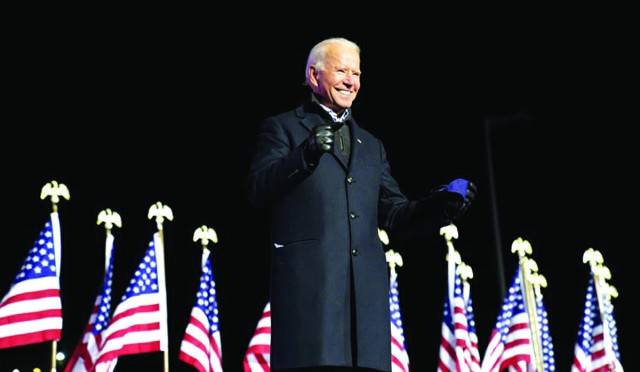

Since the assumption of office by Joe Biden as the 46th president of the United States, Pakistan has tried to reach out to the new administration. In the initial days the question was whether Biden would rewind the clock to 2016 or begin the conversation from 2021. There’s enough evidence now from his first 100 days in office to answer that question.

But before we get down to answering the above question, it is important to first explain the question itself. The eight years of Barack Obama’s two terms, especially from 2011 to 2016, were demonstrably the worst period of US-Pakistan relations in recent history. And while Biden was generally considered to be more sympathetic towards Pakistan, he was, nonetheless, a part of that administration as Obama’s vice president. The overall US policy towards Pakistan was not only transactional with a focus on Afghanistan, but the Obama administration was convinced that its failure in Afghanistan was because of Pakistan’s duplicity.

This refrain was also voiced by most US policymakers and think tankers (as some still do). The narrative was dominated by the US and its allies. The central theme of think tank papers and policy op-eds was US interests in the region and whether Pakistan was doing enough to help the US secure its interests. The narrative conveniently ignored the fact that just like the US, Pakistan had (and has) its own interests and threat perceptions in the region; and, just like the US, Pakistan would do whatever it can to safeguard them.

The real question of whether the US and Pakistani interests could be aligned and in what way was almost never asked. Call it the hubris of a hyperpower, but most US administrations and mainstream US analysts want to reserve the right of speaking out of both sides of the mouth only for the US. Corollary: in any given situation, the US interests are always holier than that of other states.

This should explain Islamabad’s query about whether Biden wants to start the conversation from 2016 or 2021. Now to the answer.

Unfortunately, except for understanding that the US needs Pakistan to get out of Afghanistan after a failed effort, the Biden administration’s approach to Pakistan remains steeped in the Obama years.

Pakistan had hoped that the administration would look towards a reset in relations. There were many signals to that end, including two important ones: Pakistan wants to focus on geoeconomics and it does not want to be thrown into one or another hostile camp. The idea of the reset therefore focused on trade and investments and a relationship that goes beyond the immediate, i.e., Afghanistan. Put another way, Pakistan has signalled that it is prepared for and wants more than a transactional relationship.

Predictably, Pakistan has been disappointed. There will be more disappointment in store unless we appreciate the fact that we do not — and never did — belong in the category of states with which the US wanted or wants a strategic partnership or a relationship that is informed by more than the immediacy of US interests.

There’s a sweet paradox here: while at one end Pakistan earned the unenviable sobriquet of America’s most allied ally and has always undersold itself, strangely enough it has also defied the US in relation to some of its (Pakistan’s) core interests. But even if Pakistan were to completely become a client state, the US would still not consider it a strategic partner. Even with allies, the US treats some allies as more allied than others.

So, what should Pakistan expect from the Biden administration?

First and foremost, let’s drop the hope that the US and Pakistan can be strategic partners or even have a relationship that is more than transactional. Once that is understood, there will be less disappointment on our side. This is not to say that Pakistan cannot have meaningful and mutually beneficial relations with the US. Au contraire, it is the very understanding and appreciation of the limits and limitations of what can be achieved that is essential in getting this done right.

Allied with this is the fact that people in power in Pakistan — on both the civilian and military side — should understand that obsequity is not going to help. There is no need to treat every arriving US official as a VIP who can meet anyone (s)he wants. Protocol is not just important, it is crucial. One can either run a country and safeguard its interests or abase oneself before sundry Americans.

Let me give a specific example: the US is still engaging with Pakistan on Afghanistan. These contacts have been and will be through Zalmay Khalilzad, the US Special Envoy or the US CENTCOM commander or the force commander in Afghanistan or some assistant secretary of state or phone-calls by US Secretary of State and/or Defence. Pakistan must ensure that whoever comes to Pakistan or calls gets to meet or talk to only his/her counterpart. No more, no less. Let’s put behind us the years when the US Secretary of State or US Senators or even ambassadorial-level officials would come here and get an audience with the President and Prime Minister of Pakistan.

One, it’s against protocol; two, a transactional relationship is all about, you guessed it, cut-and-dried, no-nonsense official exchanges.

Much is being made of Biden not having called Prime Minister Khan; also, that despite Pakistan’s efforts to combat climate change, Biden did not invite Khan to his climate change summit. Without going into any details, I will say two things here: first, it just proves what I have written above; second, Pakistan should neither be bothered nor expect the US to treat it as an ally. Since we have determined this to be a transactional relationship, the US has often sanctioned Pakistan, waived some of those sanctions in the interest of US national security and slapped them back again once Pakistan’s use has been expended.

In order for Pakistan to have meaningful relations with the US, it should identify areas where it can interest the latter. There’s potential for increasing exports; there’s a need to diversify economic and trade relations, including in the IT sector. Healthcare, education, agriculture, infrastructure development are other areas where the two sides can have useful cooperation. There’s not much likelihood of US investment coming to Pakistan. But the government could facilitate private innovators and entrepreneurs to interest US businesses to explore the Pakistani market and exploit the talent here. This said, if the US doesn’t show much interest in exploring options for engagement in areas other than where it thinks its interests lie, Pakistan should reciprocate.

In any case, beyond this lies the territory of hardcore realpolitik. The US will remain cautiously opposed to Pakistan’s development of nuclear weapons and (even more so) of long-range missiles and space launch vehicles (both crucial for Pakistan’s security). It will continue to harp on Pakistan’s “support” of non-state actors (it doesn’t matter if the US has done this itself in Syria and Libya). It will keep referring to Kashmir as an India-Pakistan problem, stay mum on Indian atrocities in occupied and illegally-annexed Kashmir, press Pakistan to make peace with India and look at the situation from a crisis-management perspective without addressing the central issue. It will keep harping on Chinese investment and CPEC, keep putting its weight behind India and continue to pressure Pakistan through FATF.

This is structural realism at work. It’s a bind which good intentions can neither break nor address, official statements and op-eds trying to make pigs fly notwithstanding.

Bottomline: expect little. Utilise areas where interests converge. But do not offer any more free or subsidised lunches to the US. After all, a transactional relationship is about interests on both sides, not just one.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider

But before we get down to answering the above question, it is important to first explain the question itself. The eight years of Barack Obama’s two terms, especially from 2011 to 2016, were demonstrably the worst period of US-Pakistan relations in recent history. And while Biden was generally considered to be more sympathetic towards Pakistan, he was, nonetheless, a part of that administration as Obama’s vice president. The overall US policy towards Pakistan was not only transactional with a focus on Afghanistan, but the Obama administration was convinced that its failure in Afghanistan was because of Pakistan’s duplicity.

This refrain was also voiced by most US policymakers and think tankers (as some still do). The narrative was dominated by the US and its allies. The central theme of think tank papers and policy op-eds was US interests in the region and whether Pakistan was doing enough to help the US secure its interests. The narrative conveniently ignored the fact that just like the US, Pakistan had (and has) its own interests and threat perceptions in the region; and, just like the US, Pakistan would do whatever it can to safeguard them.

The real question of whether the US and Pakistani interests could be aligned and in what way was almost never asked. Call it the hubris of a hyperpower, but most US administrations and mainstream US analysts want to reserve the right of speaking out of both sides of the mouth only for the US. Corollary: in any given situation, the US interests are always holier than that of other states.

This should explain Islamabad’s query about whether Biden wants to start the conversation from 2016 or 2021. Now to the answer.

Unfortunately, except for understanding that the US needs Pakistan to get out of Afghanistan after a failed effort, the Biden administration’s approach to Pakistan remains steeped in the Obama years.

Pakistan had hoped that the administration would look towards a reset in relations. There were many signals to that end, including two important ones: Pakistan wants to focus on geoeconomics and it does not want to be thrown into one or another hostile camp. The idea of the reset therefore focused on trade and investments and a relationship that goes beyond the immediate, i.e., Afghanistan. Put another way, Pakistan has signalled that it is prepared for and wants more than a transactional relationship.

Predictably, Pakistan has been disappointed. There will be more disappointment in store unless we appreciate the fact that we do not — and never did — belong in the category of states with which the US wanted or wants a strategic partnership or a relationship that is informed by more than the immediacy of US interests.

There’s a sweet paradox here: while at one end Pakistan earned the unenviable sobriquet of America’s most allied ally and has always undersold itself, strangely enough it has also defied the US in relation to some of its (Pakistan’s) core interests. But even if Pakistan were to completely become a client state, the US would still not consider it a strategic partner. Even with allies, the US treats some allies as more allied than others.

So, what should Pakistan expect from the Biden administration?

First and foremost, let’s drop the hope that the US and Pakistan can be strategic partners or even have a relationship that is more than transactional. Once that is understood, there will be less disappointment on our side. This is not to say that Pakistan cannot have meaningful and mutually beneficial relations with the US. Au contraire, it is the very understanding and appreciation of the limits and limitations of what can be achieved that is essential in getting this done right.

Allied with this is the fact that people in power in Pakistan — on both the civilian and military side — should understand that obsequity is not going to help. There is no need to treat every arriving US official as a VIP who can meet anyone (s)he wants. Protocol is not just important, it is crucial. One can either run a country and safeguard its interests or abase oneself before sundry Americans.

Let me give a specific example: the US is still engaging with Pakistan on Afghanistan. These contacts have been and will be through Zalmay Khalilzad, the US Special Envoy or the US CENTCOM commander or the force commander in Afghanistan or some assistant secretary of state or phone-calls by US Secretary of State and/or Defence. Pakistan must ensure that whoever comes to Pakistan or calls gets to meet or talk to only his/her counterpart. No more, no less. Let’s put behind us the years when the US Secretary of State or US Senators or even ambassadorial-level officials would come here and get an audience with the President and Prime Minister of Pakistan.

One, it’s against protocol; two, a transactional relationship is all about, you guessed it, cut-and-dried, no-nonsense official exchanges.

Much is being made of Biden not having called Prime Minister Khan; also, that despite Pakistan’s efforts to combat climate change, Biden did not invite Khan to his climate change summit. Without going into any details, I will say two things here: first, it just proves what I have written above; second, Pakistan should neither be bothered nor expect the US to treat it as an ally. Since we have determined this to be a transactional relationship, the US has often sanctioned Pakistan, waived some of those sanctions in the interest of US national security and slapped them back again once Pakistan’s use has been expended.

In order for Pakistan to have meaningful relations with the US, it should identify areas where it can interest the latter. There’s potential for increasing exports; there’s a need to diversify economic and trade relations, including in the IT sector. Healthcare, education, agriculture, infrastructure development are other areas where the two sides can have useful cooperation. There’s not much likelihood of US investment coming to Pakistan. But the government could facilitate private innovators and entrepreneurs to interest US businesses to explore the Pakistani market and exploit the talent here. This said, if the US doesn’t show much interest in exploring options for engagement in areas other than where it thinks its interests lie, Pakistan should reciprocate.

In any case, beyond this lies the territory of hardcore realpolitik. The US will remain cautiously opposed to Pakistan’s development of nuclear weapons and (even more so) of long-range missiles and space launch vehicles (both crucial for Pakistan’s security). It will continue to harp on Pakistan’s “support” of non-state actors (it doesn’t matter if the US has done this itself in Syria and Libya). It will keep referring to Kashmir as an India-Pakistan problem, stay mum on Indian atrocities in occupied and illegally-annexed Kashmir, press Pakistan to make peace with India and look at the situation from a crisis-management perspective without addressing the central issue. It will keep harping on Chinese investment and CPEC, keep putting its weight behind India and continue to pressure Pakistan through FATF.

This is structural realism at work. It’s a bind which good intentions can neither break nor address, official statements and op-eds trying to make pigs fly notwithstanding.

Bottomline: expect little. Utilise areas where interests converge. But do not offer any more free or subsidised lunches to the US. After all, a transactional relationship is about interests on both sides, not just one.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider