Just 11 years after the massacre at Amritsar, British troops would kill unarmed civilians again. This time the massacre would occur at the gates of the historic city of Peshawar next to Khyber Pass, where as many as 400 people were murdered in cold blood. The official British death toll was 30 people.

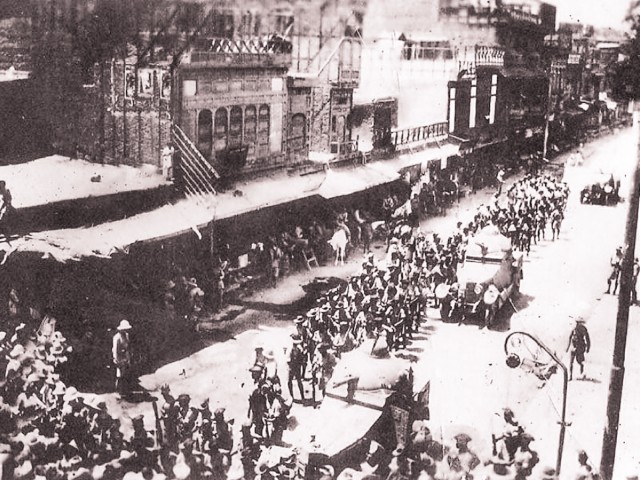

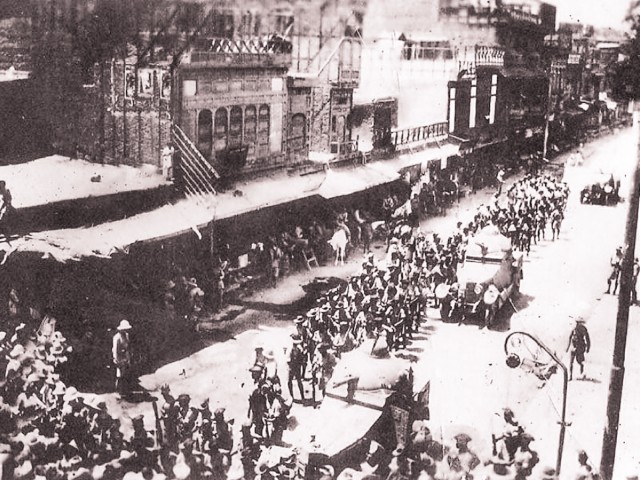

Arrests of prominent politicians in Peshawar, Ghulam Rabani and Abdur Rehman Atish while they were addressing a crowd of supporters on the morning of April 23, 1930, led to demonstrations in the Qissa Khwani Bazaar.

Deputy Commissioner of Peshawar, Metcalfe, overreacted since he feared the demonstrators. He wanted armored cars “to make reconnaissance in a position of the situation.” The sudden arrival of armored cars infuriated people, particularly since these cars drove over at least six men. At least two people were crushed and killed under these vehicles.

The cars stopped near Edwardes Gate and the crowd retaliated: they hurled bricks at the cars, symbols of an unwanted foreign military. One of the armored cars was set on fire by the protesters. District judge Saadullah Khan who observed the scene said, “I was against the armored cars and against the troops, and I was under the impression that the local police would be quite sufficient and I felt that if we did not interfere with them, they would go away.”

But it appears that the presence of armored cars fueled passions for independence and this led to the subsequent massacre of 400 people.

The crowds were shouting “inqilab zindabad” and “Allah o Akbar” and calling for the destruction of the British empire. The sloganeering was led by a young Sikh boy.

Contrary to the expectations of District Commissioner Metcalfe, the crowd was unfazed by the armored vehicles. One British witness reported that, “A member of the crowd rushed forward and seized the hand of an officer of an armored car who had an automatic pistol in his hand and tried to snatch it away. He was a very powerful man and the officer shouted for help. Several of us went to his assistance and we succeeded eventually retaining it.”

According to District Judge Saadullah Khan, the first round of shooting occurred and lasted about 10 to 15 minutes when a British officer opened fire on the crowd, followed by machine gun fire from the armored cars. Half an hour later, a second round of shooting commenced again.

The second round of shooting occurred when the 18th Royal Garwhal Rifles, facing the demonstrators, were struck by wooden sticks. One demonstrator tried to grab a rifle from one of the troops and was shot dead. However, the Royal Garwhal Rifles retreated in the face of the advancing crowd which was armed with sticks and bricks. The men of the King’s own Yorkshire Light Infantry under Major T.E.F Penny opened fire on the crowd of demonstrators.

Two armored vehicles joined in the attack with their machine guns. The shooting was so indiscriminate that even a police constable’s horse was killed. As the crowd scattered, the Yorkshire troops advanced into the bazaar of the storytellers, gunning down people mercilessly as they advanced.

Scenes of horror met the eyes of spectators. Abdul Hamid, a resident of Peshawar city said, “A young man who was probably wounded and wanted to run away after taking up his turban (which fell on the floor) was again fired at by a British soldier and killed. A man who had a baby in his arms was shot. He fell down and one of the British soldiers took the child and threw it aside. I was standing on the balcony of my brother’s office, thinking that I was safe there. A man named Elahi Baksh was standing near me. Suddenly he called out to me to get back. He told me that a British soldier levelled his gun towards me to fire, and that rounds had been fired towards another balcony. We closed the doors and hid inside.”

Ghulam Ahmad, a stretcher bearer, reported that, “There was a wounded person in Jehangirpura who was trying to get up but he could not. We attempted to rescue him but a British soldier shot him.”

Balwant Singh, 12, was taking his brother’s lunch to the shop where he worked when the massacre took place. He said, “As I reached the entrance to Dhakki Nalbandi from the Qissa Khwani side, a machine gun opened fire. People began to run up Dhakki Nalbandi. I also ran back. People around me began to fall in large numbers. I had gone a distance of about 50 yards when near the shop of Dr Behari Lal, I was hit in the left thigh. I fell down and tried to stagger to one side of the street when two Muslims came and took me up and brought me to the Lady Reading Hospital.”

Ramzan was on his way to apply for his father’s sick leave at his workplace. He entered the Kabuli Gate at around 12.30pm. “As soon as I entered from the gate, a soldier shot me...I ran back and fell by the tanners’ serai which is near the cinema. The soldier was at a distance of 20-25 paces from me. I was hit in the right shin.”

Abdul Raoof, a lawyer from Peshawar, recalled, “When I reached Edwards High School near the Kohati Gate, I met many scared people who told me that bullets had been fired in Qissa Khwani Bazaar. When I reached Egerton Hospital, people persuaded me to leave my tonga and not to go any further into the bazaar because it was too risky.” The shooting continued for two hours and was indiscriminate.

Another witness said, “Everyone who appeared in the balconies or rooftops were shot at. We closed the doors and the windows, as did the others. They were firing at the buildings to buy time to secretly remove the dead bodies. A large number of bodies were taken in closed lorries and disposed of in some unknown place. I was peeping through a hole and heard the lorries and I saw the dead bodies being packed there. I saw three such lorries. There are different rumors about their disposal.”

As many as 17 men of the Royal Garwhal rifles were imprisoned for failing to shoot the protesters. Their sentences ranged from life in exile for the most senior ranking military man, Havildar/Sergeant, Chander Singh, to imprisonment with hard labour of between three to ten years. Very few troops could afford legal representation. An MP at the time described these sentences in Parliament as being vindictive and called for a review.

On April 24, the Royal Garwhal Rifles refused to patrol Peshawar city. The Garwhal Rifles were ordered by their British officer Captain Tucker to return their rifles but they refused to comply. When asked the reason for this trouble, a non-commissioned officer named Harak S Dhapela replied, “The Indian Army is meant to protect India from external invasions and not to function inside.”

During the inquiry that followed, Justice Suleiman and Justice were perplexed by the affection of British officials for the local Pakhtun people. “Since the inquiry began, we have had statistics before us of crimes of violence which are extremely high. I think I have noticed here that although there is a large number of violent crimes, the officials seem to be positively enthusiastic about the people. What is the reason that these apparently troublesome people seem to be successful in winning the affection of the officials?”

Metcalfe responded, “With the rural population…relations have been extremely pleasant and friendly, partly because the Pathan (Pakhtun) takes a great interest in sports such as hunting, shooting and so on, and officers have an opportunity of meeting them. You will find them most friendly, very pleasant and at the same time most hospitable. That is the point which makes one like them. They extend their hospitality in a most generous measure to officers.”

This perceived bond of friendship between the British and Pakhtuns did not prevent the massacre of April 23, 1930.

But the British were not yet satisfied and the following month the scene was repeated in the old city of Peshawar, though on a slightly smaller scale. On May 31, 1930 in front of the entrance to Gor Khatri, at least six people were killed and eight wounded from a funeral procession which had been fired upon by soldiers from the Essex Regiment. The funeral procession was for Sikh children who had been murdered that very day by British troops in Peshawar. Our histories have been written by the likes of Olaf Caroe, who was a participant in this bloodstained story, and his book reflects his amnesia regarding the crimes committed by the British military. It is indeed tragic that his writings continue to be regarded by many Pakhtuns in Pakistan as being representative of our history.

Today there may no longer be storytellers in the bazaar but the crimes committed on April 23, 1930 were rendered immortal by the classic Pashto story of Habib Nur.

Nur heard about the massacre from his uncle and he was newly married, he resolved to take revenge. Nur decided to kill the British Assistant Commissioner in Charsadda. Armed with a locally produced revolver, he entered the British official’s office and pointed the revolver at the forehead of his intended victim, only to find the indigenous revolver betrayed him and jammed. Nur was detained by the police and hanged the very next day without trial.

The death of storytelling in our times does not mean that the massacre of those slaughtered by foreign troops is forgotten or forgiven. While the massacre at Amritsar has led to British expressions of contrition, no Pakistani official has asked for an apology for the slaughter in Peshawar in 1930.

The writer is the author of Afghanistan in the Age of Empires

Arrests of prominent politicians in Peshawar, Ghulam Rabani and Abdur Rehman Atish while they were addressing a crowd of supporters on the morning of April 23, 1930, led to demonstrations in the Qissa Khwani Bazaar.

Deputy Commissioner of Peshawar, Metcalfe, overreacted since he feared the demonstrators. He wanted armored cars “to make reconnaissance in a position of the situation.” The sudden arrival of armored cars infuriated people, particularly since these cars drove over at least six men. At least two people were crushed and killed under these vehicles.

The cars stopped near Edwardes Gate and the crowd retaliated: they hurled bricks at the cars, symbols of an unwanted foreign military. One of the armored cars was set on fire by the protesters. District judge Saadullah Khan who observed the scene said, “I was against the armored cars and against the troops, and I was under the impression that the local police would be quite sufficient and I felt that if we did not interfere with them, they would go away.”

But it appears that the presence of armored cars fueled passions for independence and this led to the subsequent massacre of 400 people.

The crowds were shouting “inqilab zindabad” and “Allah o Akbar” and calling for the destruction of the British empire. The sloganeering was led by a young Sikh boy.

Contrary to the expectations of District Commissioner Metcalfe, the crowd was unfazed by the armored vehicles. One British witness reported that, “A member of the crowd rushed forward and seized the hand of an officer of an armored car who had an automatic pistol in his hand and tried to snatch it away. He was a very powerful man and the officer shouted for help. Several of us went to his assistance and we succeeded eventually retaining it.”

According to District Judge Saadullah Khan, the first round of shooting occurred and lasted about 10 to 15 minutes when a British officer opened fire on the crowd, followed by machine gun fire from the armored cars. Half an hour later, a second round of shooting commenced again.

The second round of shooting occurred when the 18th Royal Garwhal Rifles, facing the demonstrators, were struck by wooden sticks. One demonstrator tried to grab a rifle from one of the troops and was shot dead. However, the Royal Garwhal Rifles retreated in the face of the advancing crowd which was armed with sticks and bricks. The men of the King’s own Yorkshire Light Infantry under Major T.E.F Penny opened fire on the crowd of demonstrators.

The death of storytelling in our times does not mean that the massacre of those slaughtered by foreign troops is forgotten or forgiven

Two armored vehicles joined in the attack with their machine guns. The shooting was so indiscriminate that even a police constable’s horse was killed. As the crowd scattered, the Yorkshire troops advanced into the bazaar of the storytellers, gunning down people mercilessly as they advanced.

Scenes of horror met the eyes of spectators. Abdul Hamid, a resident of Peshawar city said, “A young man who was probably wounded and wanted to run away after taking up his turban (which fell on the floor) was again fired at by a British soldier and killed. A man who had a baby in his arms was shot. He fell down and one of the British soldiers took the child and threw it aside. I was standing on the balcony of my brother’s office, thinking that I was safe there. A man named Elahi Baksh was standing near me. Suddenly he called out to me to get back. He told me that a British soldier levelled his gun towards me to fire, and that rounds had been fired towards another balcony. We closed the doors and hid inside.”

Ghulam Ahmad, a stretcher bearer, reported that, “There was a wounded person in Jehangirpura who was trying to get up but he could not. We attempted to rescue him but a British soldier shot him.”

Balwant Singh, 12, was taking his brother’s lunch to the shop where he worked when the massacre took place. He said, “As I reached the entrance to Dhakki Nalbandi from the Qissa Khwani side, a machine gun opened fire. People began to run up Dhakki Nalbandi. I also ran back. People around me began to fall in large numbers. I had gone a distance of about 50 yards when near the shop of Dr Behari Lal, I was hit in the left thigh. I fell down and tried to stagger to one side of the street when two Muslims came and took me up and brought me to the Lady Reading Hospital.”

Ramzan was on his way to apply for his father’s sick leave at his workplace. He entered the Kabuli Gate at around 12.30pm. “As soon as I entered from the gate, a soldier shot me...I ran back and fell by the tanners’ serai which is near the cinema. The soldier was at a distance of 20-25 paces from me. I was hit in the right shin.”

Abdul Raoof, a lawyer from Peshawar, recalled, “When I reached Edwards High School near the Kohati Gate, I met many scared people who told me that bullets had been fired in Qissa Khwani Bazaar. When I reached Egerton Hospital, people persuaded me to leave my tonga and not to go any further into the bazaar because it was too risky.” The shooting continued for two hours and was indiscriminate.

Another witness said, “Everyone who appeared in the balconies or rooftops were shot at. We closed the doors and the windows, as did the others. They were firing at the buildings to buy time to secretly remove the dead bodies. A large number of bodies were taken in closed lorries and disposed of in some unknown place. I was peeping through a hole and heard the lorries and I saw the dead bodies being packed there. I saw three such lorries. There are different rumors about their disposal.”

As many as 17 men of the Royal Garwhal rifles were imprisoned for failing to shoot the protesters. Their sentences ranged from life in exile for the most senior ranking military man, Havildar/Sergeant, Chander Singh, to imprisonment with hard labour of between three to ten years. Very few troops could afford legal representation. An MP at the time described these sentences in Parliament as being vindictive and called for a review.

On April 24, the Royal Garwhal Rifles refused to patrol Peshawar city. The Garwhal Rifles were ordered by their British officer Captain Tucker to return their rifles but they refused to comply. When asked the reason for this trouble, a non-commissioned officer named Harak S Dhapela replied, “The Indian Army is meant to protect India from external invasions and not to function inside.”

During the inquiry that followed, Justice Suleiman and Justice were perplexed by the affection of British officials for the local Pakhtun people. “Since the inquiry began, we have had statistics before us of crimes of violence which are extremely high. I think I have noticed here that although there is a large number of violent crimes, the officials seem to be positively enthusiastic about the people. What is the reason that these apparently troublesome people seem to be successful in winning the affection of the officials?”

Metcalfe responded, “With the rural population…relations have been extremely pleasant and friendly, partly because the Pathan (Pakhtun) takes a great interest in sports such as hunting, shooting and so on, and officers have an opportunity of meeting them. You will find them most friendly, very pleasant and at the same time most hospitable. That is the point which makes one like them. They extend their hospitality in a most generous measure to officers.”

This perceived bond of friendship between the British and Pakhtuns did not prevent the massacre of April 23, 1930.

But the British were not yet satisfied and the following month the scene was repeated in the old city of Peshawar, though on a slightly smaller scale. On May 31, 1930 in front of the entrance to Gor Khatri, at least six people were killed and eight wounded from a funeral procession which had been fired upon by soldiers from the Essex Regiment. The funeral procession was for Sikh children who had been murdered that very day by British troops in Peshawar. Our histories have been written by the likes of Olaf Caroe, who was a participant in this bloodstained story, and his book reflects his amnesia regarding the crimes committed by the British military. It is indeed tragic that his writings continue to be regarded by many Pakhtuns in Pakistan as being representative of our history.

Today there may no longer be storytellers in the bazaar but the crimes committed on April 23, 1930 were rendered immortal by the classic Pashto story of Habib Nur.

Nur heard about the massacre from his uncle and he was newly married, he resolved to take revenge. Nur decided to kill the British Assistant Commissioner in Charsadda. Armed with a locally produced revolver, he entered the British official’s office and pointed the revolver at the forehead of his intended victim, only to find the indigenous revolver betrayed him and jammed. Nur was detained by the police and hanged the very next day without trial.

The death of storytelling in our times does not mean that the massacre of those slaughtered by foreign troops is forgotten or forgiven. While the massacre at Amritsar has led to British expressions of contrition, no Pakistani official has asked for an apology for the slaughter in Peshawar in 1930.

The writer is the author of Afghanistan in the Age of Empires