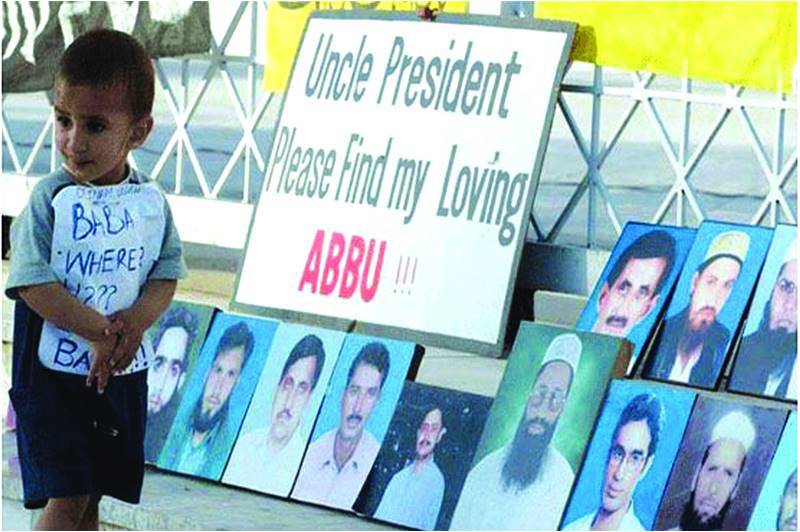

August 30 marks the International Year of the Disappeared. It is an important occasion to reflect on the plight of those who were mysteriously kidnapped from their homes and have remained untraced for years, their families enduring indescribable pain and agony.

The international community defines enforced disappearance as, “the arrest, detention, abduction...by agents of the State or by persons...acting with the...support of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge (it) or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

Involving as it does a serious violation of several fundamental rights - including the right to life, right to be free from torture and degrading treatment, right against arbitrary detention and the right to fair trial - enforced disappearances is a very serious crime. That is why the international community has adopted convention against it and has urged all states to criminalise enforced disappearances and bring to account the perpetrators of the crime, besides providing compensation and rehabilitation of the victims and their families.

The phenomenon of enforced disappearances has been witnessed in Pakistan for over quarter of a century, if not earlier. However, it has stepped up since 9/11 with the increasing militarisation of state and society and the new phenomenon of backseat driving of statecraft by unaccountable elements.

Former military dictator General Pervez Musharraf in his memoirs admitted to handing over hundreds of suspects to the CIA without due process. “We handed over 369 to the United States (and) earned bounties totaling millions of dollars. Those who habitually accuse us of ‘not doing enough’ in the war on terror should simply ask the CIA how much prize money it has paid.” When the confession provoked an angry response, it was deleted from the Urdu edition of the book.

At the international day of enforced disappearances last year, when the present government was barely a few days in office, the minister for human rights declared at D Chowk in Islamabad that draft legislation has been made to criminalise enforced disappearances. There was thunderous applause from the families of the victims. But a few days later, it transpired that instead of legislation, the government refused to even compensate the families as ordered by the Islamabad High Court by appealing against the verdict.

During the last one year, as the miltablishment has been legitimised and political forces delegitimised, one thing has been clear: state agencies indeed are involved in enforced disappearances. This is illustrated by the following.

First, the army spokesperson recently admitted that some missing persons were in the custody of the agencies. “Not all missing persons” were in the custody of the army, he said. He further disclosed that a “special cell on missing persons had been established in the GHQ.” Apart from the anomaly of setting up such a cell in the GHQ, or ISI, no one knows what are the terms of the special cell, how it functions, since when it was set up and what relief, if any, it has provided to the victims let alone holding the perpetrators accountable for the crime.

Second, during the last budget session of the National Assembly Akhtar Mengal, the head of BNP-M, threatened to withdraw support from the government if those missing in Balochistan for years and listed by him from time to time were not recovered. Promptly dozens of the more fortunate ones were recovered a day before the voting.

Third, not long ago the Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances disclosed during a briefing to the Senate Committee on Human Rights late last year that 153 army personnel were found involved in abducting people and that “action had been taken” against them. Relevant extracts from the minutes of the August 28, 2018 meeting at the Parliament House states:

“The Chairman Committee inquired if any action had been initiated against those individuals who were thought to be involved in abducting people and depriving missing persons of their liberty. The Committee was apprised that action had been taken against 153 army personnel.” Although the meeting was open to public, it was not reported by the media which in the words of Imran Khan is “freer than the media in UK.” It should not be difficult to imagine why and who may have urged the media to exercise restraint and self-censorship.

Unfortunately, the human rights ministry failed in using these confessions to take forward the conversation on missing persons.

Some years ago, internment centres were set up in erstwhile tribal areas and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the missing and disappeared were lodged, incommunicado and without trial for years, by state agencies. According to recent press reports, some inmates have disappeared even from these centres when the courts demanded that they be produced before it.

Last week, a PTM activist, Ismail Mehsud, was abducted from the centre of Islamabad in broad daylight, allegedly by plain-clothed personnel of law enforcing agencies. The case of rights activist Gulalai Ismail reveals the state’s contemptuous disregard. While the UN mission in Geneva has been informed that she is police custody, her parents have complained that their house was being repeatedly raided in search of her.

Therefore, on this international day, the state needs to make a declaration: instead of sporadic efforts to recover some missing persons under duress, it will focus on prevention of enforced disappearances and punishing those involved. The confessions made by state functionaries during the last one year will, sooner or later, attract adverse international attention. FATF is enough of a burden, let us not add to it. There is no point in the officials of human rights ministry turning up at some protest demonstrations only to express pious intentions and make vague promises. That time is long past.

The writer is a former member of the Senate Human Rights Committee

The international community defines enforced disappearance as, “the arrest, detention, abduction...by agents of the State or by persons...acting with the...support of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge (it) or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

Involving as it does a serious violation of several fundamental rights - including the right to life, right to be free from torture and degrading treatment, right against arbitrary detention and the right to fair trial - enforced disappearances is a very serious crime. That is why the international community has adopted convention against it and has urged all states to criminalise enforced disappearances and bring to account the perpetrators of the crime, besides providing compensation and rehabilitation of the victims and their families.

The phenomenon of enforced disappearances has been witnessed in Pakistan for over quarter of a century, if not earlier. However, it has stepped up since 9/11 with the increasing militarisation of state and society and the new phenomenon of backseat driving of statecraft by unaccountable elements.

The state needs to make a declaration: instead of sporadic efforts to recover some missing persons under duress, it will focus on prevention of enforced disappearances and punishing those involved

Former military dictator General Pervez Musharraf in his memoirs admitted to handing over hundreds of suspects to the CIA without due process. “We handed over 369 to the United States (and) earned bounties totaling millions of dollars. Those who habitually accuse us of ‘not doing enough’ in the war on terror should simply ask the CIA how much prize money it has paid.” When the confession provoked an angry response, it was deleted from the Urdu edition of the book.

At the international day of enforced disappearances last year, when the present government was barely a few days in office, the minister for human rights declared at D Chowk in Islamabad that draft legislation has been made to criminalise enforced disappearances. There was thunderous applause from the families of the victims. But a few days later, it transpired that instead of legislation, the government refused to even compensate the families as ordered by the Islamabad High Court by appealing against the verdict.

During the last one year, as the miltablishment has been legitimised and political forces delegitimised, one thing has been clear: state agencies indeed are involved in enforced disappearances. This is illustrated by the following.

First, the army spokesperson recently admitted that some missing persons were in the custody of the agencies. “Not all missing persons” were in the custody of the army, he said. He further disclosed that a “special cell on missing persons had been established in the GHQ.” Apart from the anomaly of setting up such a cell in the GHQ, or ISI, no one knows what are the terms of the special cell, how it functions, since when it was set up and what relief, if any, it has provided to the victims let alone holding the perpetrators accountable for the crime.

Second, during the last budget session of the National Assembly Akhtar Mengal, the head of BNP-M, threatened to withdraw support from the government if those missing in Balochistan for years and listed by him from time to time were not recovered. Promptly dozens of the more fortunate ones were recovered a day before the voting.

Third, not long ago the Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances disclosed during a briefing to the Senate Committee on Human Rights late last year that 153 army personnel were found involved in abducting people and that “action had been taken” against them. Relevant extracts from the minutes of the August 28, 2018 meeting at the Parliament House states:

“The Chairman Committee inquired if any action had been initiated against those individuals who were thought to be involved in abducting people and depriving missing persons of their liberty. The Committee was apprised that action had been taken against 153 army personnel.” Although the meeting was open to public, it was not reported by the media which in the words of Imran Khan is “freer than the media in UK.” It should not be difficult to imagine why and who may have urged the media to exercise restraint and self-censorship.

Unfortunately, the human rights ministry failed in using these confessions to take forward the conversation on missing persons.

Some years ago, internment centres were set up in erstwhile tribal areas and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the missing and disappeared were lodged, incommunicado and without trial for years, by state agencies. According to recent press reports, some inmates have disappeared even from these centres when the courts demanded that they be produced before it.

Last week, a PTM activist, Ismail Mehsud, was abducted from the centre of Islamabad in broad daylight, allegedly by plain-clothed personnel of law enforcing agencies. The case of rights activist Gulalai Ismail reveals the state’s contemptuous disregard. While the UN mission in Geneva has been informed that she is police custody, her parents have complained that their house was being repeatedly raided in search of her.

Therefore, on this international day, the state needs to make a declaration: instead of sporadic efforts to recover some missing persons under duress, it will focus on prevention of enforced disappearances and punishing those involved. The confessions made by state functionaries during the last one year will, sooner or later, attract adverse international attention. FATF is enough of a burden, let us not add to it. There is no point in the officials of human rights ministry turning up at some protest demonstrations only to express pious intentions and make vague promises. That time is long past.

The writer is a former member of the Senate Human Rights Committee