In the Bronze Age, societies around the globe were dominated by men. Even today, in much of the world, that tradition holds true. There are a few exceptions in the developed world, notably in Europe and in the Asia-Pacific region, but even in the US a woman has yet to take the helm.

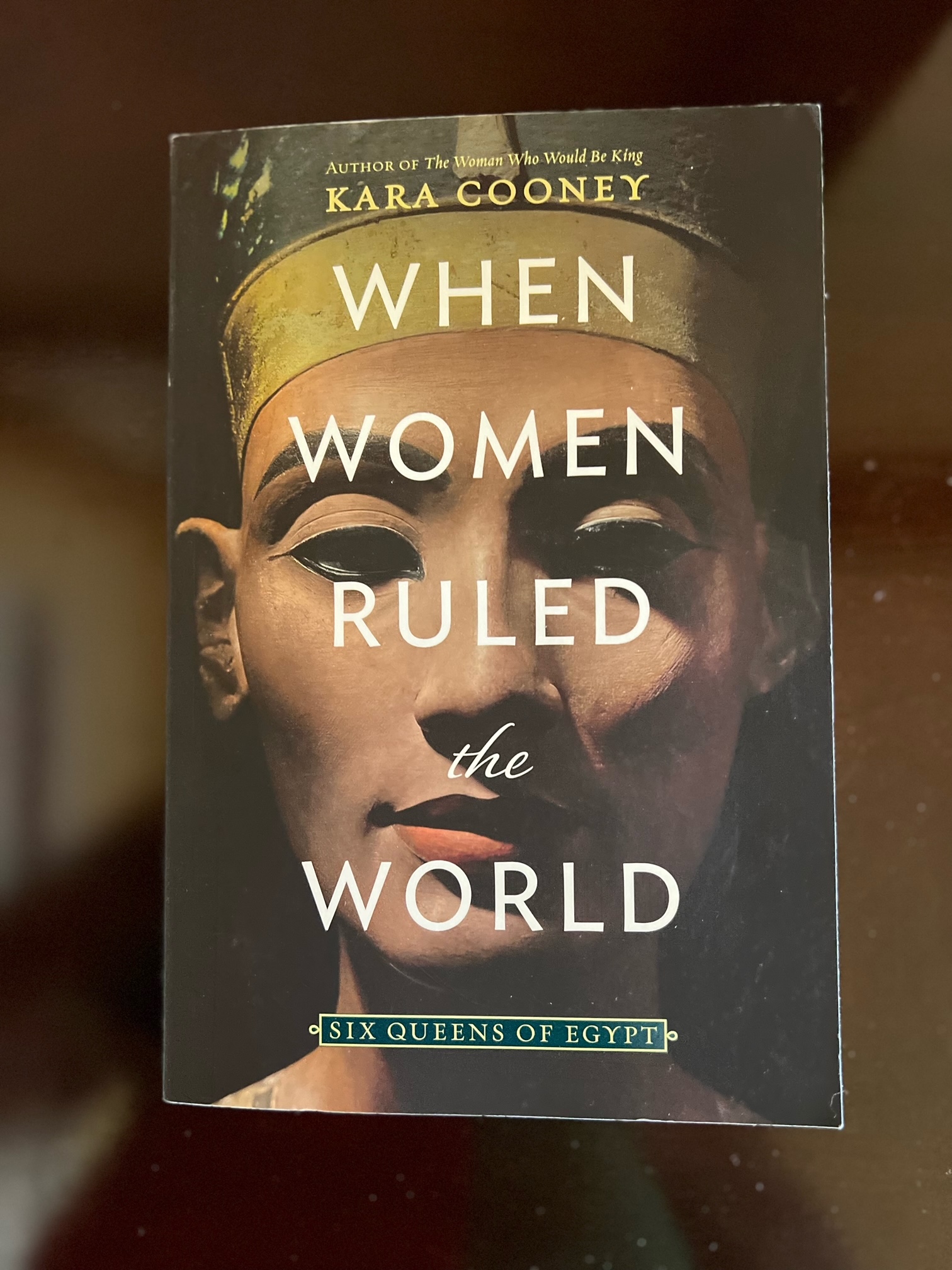

So how is it that women come to rule ancient Egypt, of all places? Professor Kara Cooney of UCLA explores this question in her book, “When Women Ruled the World.” Her narration, thankfully, is accessible to the general reader, unlike many academic tones on the topic. In fact, I found it to be mesmerizing. For those who are interested in digging deeper, she also provides nearly 60 pages of notes and scholarly citations.

The last time a woman governed Egypt was two millennia ago. This was the time of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Cleopatra ruled Egypt. She was brought to life for me by Hollywood in an eponymous film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. I hear that a new biopic about her is in the making. Volumes have been written about Cleopatra, including a fairly recent book by Stacy Schiff.

The first time I heard of Egypt was in grade school in Sukkur. We visited the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro. I learned that it was a civilisation contemporaneous with the Egyptian civilization that had built the Great Pyramids at Giza near Cairo.

My curiosity was piqued. Who were the pharaohs? Once again, Hollywood helped with the film, The Ten Commandments. It brought Ramses II to life. Some said he was the pharaoh who is mentioned in the Muslim scripture.

In the mid-1980s, I had my first contact with a few relics of ancient Egypt at the Rosicrucian Museum in San Jose. They also had several simulated relics, including one of the Rosetta Stone. But there was no evidence that women had governed Egypt.

The opportunity to visit Egypt finally arrived in November 1996. I checked out the Pyramids at Giza and went to Alexandria where I toured the harbor and the Roman ruins. There was no sign of the tomb of Cleopatra. I visited Alexandria a second time in September 2009. Once again, I failed to find any evidence of her tomb. It’s waiting to be discovered.

There is little doubt that she existed. Kara Cooney tells us she was the sixth queen to rule Egypt. The first one was Merneith who ruled Egypt some 5,000 years ago. Given that date, it’s difficult to find much evidence about her reign, other than “a jumble of architectural funerary evidence, punctuated by hieroglyphic inscriptions,” which is often indecipherable because Egyptian writing was in its earliest stages. Other than being a trailblazer for rule by women, she has not left behind much of a legacy.

Centuries later, she was followed by another woman, Neferusobek, who ruled as head of state without any male accompaniment. Her major accomplishment was that “she protected her land in a time of distress.” Her name was preserved by the Egyptians in their list of kings; she “wasn’t considered heretical or undeserving” because of her gender.

Then came the famous Hatshepsut. She ruled for more than two decades, longer than any other female ruler in ancient Egypt. “She had a foundation of ideological, political, economic and priestly support.”

She used a new instrument to endow herself with power: “Political-divine revelation,” an instrument that many others in history would use including Constantine of Rome and the Ayatollah Khomeini of present-day Iran. When she died, she was buried with full respect for her royal status, as evidenced in the archaeological discoveries in the Valley of the Kings.

She used a new instrument to endow herself with power: “Political-divine revelation,” an instrument that many others in history would use including Constantine of Rome and the Ayatollah Khomeini of present-day Iran. When she died, she was buried with full respect for her royal status, as evidenced in the archaeological discoveries in the Valley of the Kings.

Next came Nefertiti. Her limestone bust, housed in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum, has immortalised her beauty. If the bust is an accurate portrayal, says Cooney, she must have been stunning to behold. But there was more to her than her beauty.

Her rule is only beginning to be understood. Egyptologists are locked in a fierce debate about her changing nature, identity and role. Her tomb has yet to be found and Cooney tells us that until that is found, she “will remain known only for beauty in the Berlin bust, not for her reinstatement of traditional Egyptian religion.”

Her husband, Akhenaten, a religious zealot, caused immense harm to Egypt. After his death, Nefertiti began working hard to fix the destructive decisions he had made, which almost reduced Egypt to ruin. She was a consensus builder who embraced multiple perspectives and reached out to Egyptians in a spirit of accommodation. She was not an authoritarian ruler, like so many in history.

The next Egyptian queen was Tawosret, who began her life during the latter part of the 67-year reign of Ramses II, or Ramses the Great. By the time she became queen, Egypt had become globalized, replete with people from the Levant, Syria and other far-off places. She is unique in that she seized power by force, and refused to share it with a male partner. She commissioned statues of herself showing her as having the bust of a woman but wearing masculine kilts like those of Ramses II.

Her reign was too short for her to accomplish anything of substance. She knew she was no Hatshepsut, but she ruled with confidence. After her demise, Egypt would not see another female ruler for another thousand years.

Egypt was under constant attack from the Assyrians, followed by the Babylonians, the Persians, and Alexander the Great. Finally, Egypt fell to the Greeks. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Macedonia ruled over Egypt for three centuries, the longest in all of Egyptian history.

The last ruler of that dynasty was Cleopatra, who Cooney calls the Drama Queen. In her judgment, she stood head and shoulders above the five prior queens.

Her affairs with Caesar and Antony after the former’s assassination are as well documented in history as they are in literature. More for political than emotional reasons, she bore children outside of wedlock with both of the men, hoping to ingratiate herself with the Roman nobility, on which the Egyptians depended for financial survival.

Unfortunately, as much for her as for Egypt, her partnership with Antony came to an end a year after their combined militaries lost to Octavian at the Battle of Actium. She and Antony committed suicide and were apparently buried somewhere near Alexandria, in a tomb that’s waiting to be discovered.

With Cleopatra’s death, an era ended in Egyptian history. No woman would ever rule Egypt again.

So how is it that women come to rule ancient Egypt, of all places? Professor Kara Cooney of UCLA explores this question in her book, “When Women Ruled the World.” Her narration, thankfully, is accessible to the general reader, unlike many academic tones on the topic. In fact, I found it to be mesmerizing. For those who are interested in digging deeper, she also provides nearly 60 pages of notes and scholarly citations.

The last time a woman governed Egypt was two millennia ago. This was the time of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Cleopatra ruled Egypt. She was brought to life for me by Hollywood in an eponymous film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. I hear that a new biopic about her is in the making. Volumes have been written about Cleopatra, including a fairly recent book by Stacy Schiff.

The first time I heard of Egypt was in grade school in Sukkur. We visited the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro. I learned that it was a civilisation contemporaneous with the Egyptian civilization that had built the Great Pyramids at Giza near Cairo.

My curiosity was piqued. Who were the pharaohs? Once again, Hollywood helped with the film, The Ten Commandments. It brought Ramses II to life. Some said he was the pharaoh who is mentioned in the Muslim scripture.

In the mid-1980s, I had my first contact with a few relics of ancient Egypt at the Rosicrucian Museum in San Jose. They also had several simulated relics, including one of the Rosetta Stone. But there was no evidence that women had governed Egypt.

The opportunity to visit Egypt finally arrived in November 1996. I checked out the Pyramids at Giza and went to Alexandria where I toured the harbor and the Roman ruins. There was no sign of the tomb of Cleopatra. I visited Alexandria a second time in September 2009. Once again, I failed to find any evidence of her tomb. It’s waiting to be discovered.

There is little doubt that she existed. Kara Cooney tells us she was the sixth queen to rule Egypt. The first one was Merneith who ruled Egypt some 5,000 years ago. Given that date, it’s difficult to find much evidence about her reign, other than “a jumble of architectural funerary evidence, punctuated by hieroglyphic inscriptions,” which is often indecipherable because Egyptian writing was in its earliest stages. Other than being a trailblazer for rule by women, she has not left behind much of a legacy.

Centuries later, she was followed by another woman, Neferusobek, who ruled as head of state without any male accompaniment. Her major accomplishment was that “she protected her land in a time of distress.” Her name was preserved by the Egyptians in their list of kings; she “wasn’t considered heretical or undeserving” because of her gender.

Then came the famous Hatshepsut. She ruled for more than two decades, longer than any other female ruler in ancient Egypt. “She had a foundation of ideological, political, economic and priestly support.”

She used a new instrument to endow herself with power: “Political-divine revelation,” an instrument that many others in history would use including Constantine of Rome and the Ayatollah Khomeini of present-day Iran. When she died, she was buried with full respect for her royal status, as evidenced in the archaeological discoveries in the Valley of the Kings.

She used a new instrument to endow herself with power: “Political-divine revelation,” an instrument that many others in history would use including Constantine of Rome and the Ayatollah Khomeini of present-day Iran. When she died, she was buried with full respect for her royal status, as evidenced in the archaeological discoveries in the Valley of the Kings.Next came Nefertiti. Her limestone bust, housed in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum, has immortalised her beauty. If the bust is an accurate portrayal, says Cooney, she must have been stunning to behold. But there was more to her than her beauty.

Her rule is only beginning to be understood. Egyptologists are locked in a fierce debate about her changing nature, identity and role. Her tomb has yet to be found and Cooney tells us that until that is found, she “will remain known only for beauty in the Berlin bust, not for her reinstatement of traditional Egyptian religion.”

Her husband, Akhenaten, a religious zealot, caused immense harm to Egypt. After his death, Nefertiti began working hard to fix the destructive decisions he had made, which almost reduced Egypt to ruin. She was a consensus builder who embraced multiple perspectives and reached out to Egyptians in a spirit of accommodation. She was not an authoritarian ruler, like so many in history.

The next Egyptian queen was Tawosret, who began her life during the latter part of the 67-year reign of Ramses II, or Ramses the Great. By the time she became queen, Egypt had become globalized, replete with people from the Levant, Syria and other far-off places. She is unique in that she seized power by force, and refused to share it with a male partner. She commissioned statues of herself showing her as having the bust of a woman but wearing masculine kilts like those of Ramses II.

Her reign was too short for her to accomplish anything of substance. She knew she was no Hatshepsut, but she ruled with confidence. After her demise, Egypt would not see another female ruler for another thousand years.

Egypt was under constant attack from the Assyrians, followed by the Babylonians, the Persians, and Alexander the Great. Finally, Egypt fell to the Greeks. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Macedonia ruled over Egypt for three centuries, the longest in all of Egyptian history.

The last ruler of that dynasty was Cleopatra, who Cooney calls the Drama Queen. In her judgment, she stood head and shoulders above the five prior queens.

Her affairs with Caesar and Antony after the former’s assassination are as well documented in history as they are in literature. More for political than emotional reasons, she bore children outside of wedlock with both of the men, hoping to ingratiate herself with the Roman nobility, on which the Egyptians depended for financial survival.

Unfortunately, as much for her as for Egypt, her partnership with Antony came to an end a year after their combined militaries lost to Octavian at the Battle of Actium. She and Antony committed suicide and were apparently buried somewhere near Alexandria, in a tomb that’s waiting to be discovered.

With Cleopatra’s death, an era ended in Egyptian history. No woman would ever rule Egypt again.