This August, Chief Justice of Pakistan Qazi Faiz Isa launched a significant initiative for judicial reform. This reform involves the reconstitution of the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Committee and Task Force, aiming to streamline the justice system and address the massive backlog of 2.2 million cases pending in courts nationwide. The ADR system, established under the ADR Act of 2017, is supported by comprehensive provincial frameworks, offering a promising approach to expediting dispute resolution in a cost-effective manner.

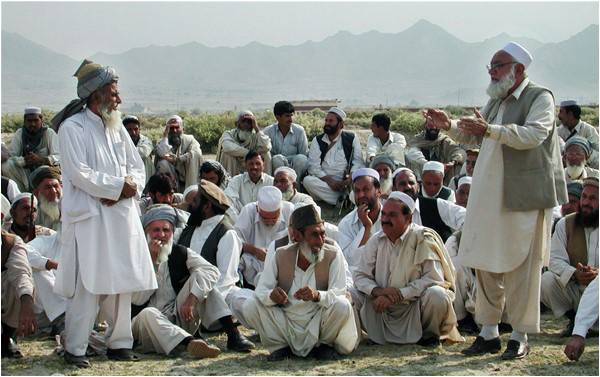

In its fundamental definition, ADR comprises a set of processes designed to resolve disputes outside of formal litigation, utilising methods such as arbitration, mediation, and conciliation. Historically, the concept of resolving disputes without recourse to legal proceedings has a long tradition in the region, predating the establishment of Pakistan. This tradition was embodied in various uncodified systems based on unwritten, community-specific customs, with the jirga being the most prominent example. Originating from the Aryan tribes living in what is known today as Afghanistan and India, the jirga has evolved into a community-centred mechanism for resolving disputes, mediating conflicts, and ensuring justice.

However, despite its historical significance, the jirga system has also been a source of concern. Its patriarchal structure, lack of codified rules, absence of legal precedents, decisions which stood contrary to settled law, potential for human rights violations, particularly against women, and ultimately its evolution into a parallel justice system operating outside the realm of the Constitution and codified laws prompted the Supreme Court of Pakistan to declare it as unlawful.

Nonetheless, jirgas have continued to persist, largely due to their deep cultural roots and the pervasive lack of trust in the state's lengthy and costly formal judicial systems. Moreover, state-run ADR systems remain insufficient as an alternative due to the lack of formalisation and enforcement of their mechanisms and the lack of awareness. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) has presented a sliver of hope in this regard with the creation of the Dispute Resolution Councils (DRCs), established under the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Police Order (Amendment Act) 2015.

To benefit from the popularity and efficiency of the traditional jirga system, the DRC has borrowed its structural and functional framework. Functioning at the district level, and in some tehsils, across the province, they provide restorative justice employing a grassroots approach to maintaining Indigenous cultural practices while addressing modern challenges. DRCs integrate traditional methods with modern legal frameworks, involving community members, including elders from jirgas, to act as jurors under the government's watchful eye.

In contrast to jirgas, which rely on village elders who cannot understand complex issues and are perceived as biased, particularly against minorities and women, DRCs are flexible in their approach

The DRCs' mechanisms and procedures are seen as more dependable, with stakeholders from diverse ethnic and gender backgrounds who are competent and impartial. In an interview with a DRC jury member, she noted that these councils provide equal rights to all individuals, including women, people who are transgender, and minorities. They have even had transgender and female members in leadership roles. This practice provides the forum with a more inclusive, transparent, and reliable outlook compared to traditional Jirgas.

Like jirgas, DRCs are deeply rooted in cultural norms and traditions, enabling them to address the root causes of conflicts with a focus on reconciliation. In contrast to jirgas, which rely on village elders who cannot understand complex issues and are perceived as biased, particularly against minorities and women, DRCs are flexible in their approach.

The DRCs provide a hybrid approach that acknowledges the strengths of both systems while addressing their weaknesses, which could be advantageous. However, the DRC system is not without its flaws. In some cases, the DRCs have perpetuated the same negative qualities as the traditional jirgas they were supposed to replace and improve upon. Reports indicate that under the platform of the DRC, corruption and bribery have been legalised, with the forum allegedly demanding large sums to broker settlements. Additionally, DRCs are often located within police stations, making it difficult for women to access them. Due to cultural barriers, many women feel intimidated or ashamed to approach male-dominated spaces such as police stations, where they fear judgment, harassment, or stigmatisation, further discouraging them from seeking help.

The question remains, whether these modern ADR systems can truly replace traditional jirgas, particularly in rural and tribal areas, where they continue to hold significant influence, especially in criminal matters for which ADR lacks precedence. Their persistence suggests that state-sanctioned ADR mechanisms have yet to fully replace or even coexist seamlessly with traditional systems, let alone phase them out.

Nevertheless, DRCs hold great potential. By fostering a more inclusive, transparent, and accountable ADR framework codified in law such as the DRC, Pakistan can move towards a more just and equitable society, where traditional and modern justice systems complement rather than compete with each other. Reforms undertaken in DRCs should ensure inclusivity, stringent monitoring, and broader public awareness. Moreover, these systems should be expanded to other provinces, such as Balochistan, a deeply troubled area where the jirga system remains prevalent, but ADR laws are weak and ill-enforced.