‘Allowing public servants (the judiciary) to act with impunity cannot be tolerated in a society that professes to be committed to upholding the rule of law’.

The resignation of judges either during the pendency of proceedings against them before the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) or before such proceedings can be brought against an errant judge on allegations of misconduct and breach of the code of ethics of judges, he retires, has always been a problem due to the inherent defect in Article 209 of the Constitution. In either eventuality, the matter ends without resolution either way and the reference premised on allegations of misconduct abates. This creates a perception that judges operate with impunity, hinders access to justice and affects the independence of the judiciary.

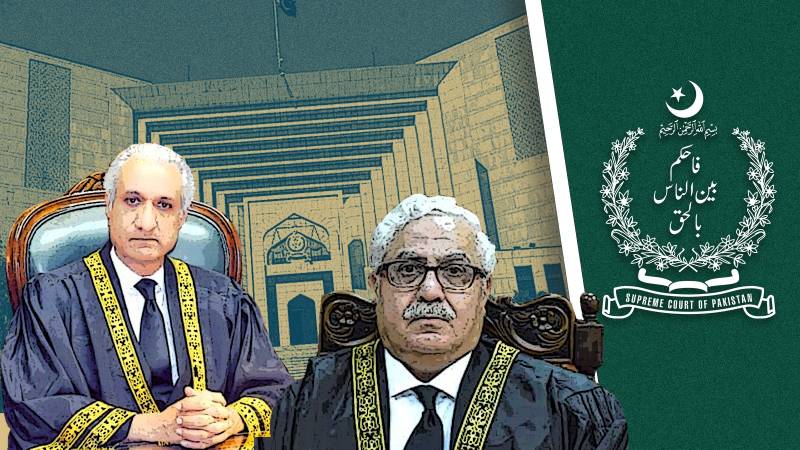

Take for instance the 2018 reference filed by Afiya Shehrbano Zia and 97 other people against the former Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP), namely, Mian Saqib Nisar. The SJC dismissed the reference vide Order dated March 8, 2019, not because the allegations were unfounded or lack of evidence, but rather due to the former CJP retiring on 17.01.2019 before any decision could be reached. This order was assailed by invoking the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) of the Constitution (known as the ‘Afiya Shehrbano case’). The fate of the Afiya Shehrbano case was dismissal of the constitutional petition, which the federal government has now appealed in an intra-court appeal under Section 5 of the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Act of 2023.

Although the reasoning given by the Supreme Court in the Afiya Shehrbano case was legally sound, the dismissal of the reference gave the public a wrong perception that errant judges, despite their misconduct or violation of their oath, judges are above the law. If proceedings are brought against them, either no action will be taken till said errant judge has retired or the errant judge can simply resign from his post while collecting the benefits for retired judges. It is equally wrong for the judge alleged against because despite their innocence, the noose of mere frivolous allegations would inadvertently still hang around their reputation, without there being any means for redressal of such grievance. Take for instance the case of Justice Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqbi. No one knows for certain if he was in fact guilty of misconduct or if the allegations were vexatious.

The issue is that even a perception of the involvement of a judge in misconduct extends the infringement to the cardinal rights of the public at large, namely, the sacrosanct right of access to justice under Article 4 read with Article 9 of the Constitution. This right is equally found in the doctrine of due process of law. In Sharaf Faridi, a 7-member-bench of the High Court of Sindh held that access to justice and due process include that ‘the tribunal or court before which his rights are adjudicated is so constituted as to give reasonable assurance of his honesty and impartiality’.

Any such perception, though it may ultimately be established to be wrong, obviously sends a message to the masses that in their quest for justice, they'll get none due to dishonesty and misconduct on the part of the bench. This fear or threat definitely has devastating consequences for society, and its citizens as people refrain from bringing forth their grievances before the Court designed to give them justice. Nothing impedes access to justice more than the fear or perception that the judiciary, instead of protecting fundamental rights and giving justice, is involved or complacent in misconduct and that too with complete impunity. Removing such a perception becomes a duty of the State.

The State ought to have abided by its duty to remove such perception by amending Article 209 of the Constitution, instead of appealing the decision and that too after the lapse of the limitation duration.

It goes without saying that there is no cavil to the notion that once proceedings are instituted against an alleged errant judge, they should be brought to a logical conclusion. However, the current framework of the Constitution does not allow for that to happen. Article 209, in its current form, under clause (6) provides for one course for the protection of the integrity and independence of the judiciary, in addition to protecting the fundamental right of access to justice, namely, the removal of a Judge. The sole intent of Article 209, evident from the perusal of its clause (7), is the removal of an errant judge.

One way of interpreting Article 209, as the State has done while laying a challenge to the Afiya Shehrbano case, is that once SJC proceedings have been initiated, they should be brought to a logical conclusion, even if a judge resigns. The problem with this approach is that redundancy cannot be attributed to any provision or clause thereunder of the Constitution, which leads to judicial law-making, thereby violating the sacred principle of Separation of Powers.

Redundancy will attributed to Article 209 in two ways (both may be over/underlapping): the first is that by interpreting Article 209 beyond its original intent (removal of a judge), by reading words into the text of the Constitution, which is not permissible, the Supreme Court would effectively nullify clause (6) of Article 209; the other is, by allowing a different outcome as opposed to the outcome envisaged therein, every time the new option or outcome created by the Supreme Court would be used, Article 209 would be sidestepped, therefore, made redundant. This leads to the issue of judicial law-making. The very notion is nauseating. Judges should confine themselves to interpreting the law and Constitution, not violate the doctrine of Separation of Powers and overstep into the realm of Parliament.

This issue should be resolved through a Constitutional Amendment in Article 209 by Elected Representatives of the Public, not unelected public servants, for a Constitutional Amendment is the need of the hour.