The debate on Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan is loaded with security concerns—the Taliban, Durand Line, cross-border attacks. Of course, there is a history to it, one of them being Afghanistan’s descent into conflict for more than thirty years.

One aspect of this bilateral relation that is overlooked is Pakistan’s trade with Afghanistan. As the world or this region moves towards geo-economics, as the oft-stated phrase goes, the volume of one country’s trade with another will be a moot point. We can see what is happening when we come across partially heated debates on the ports being developed in the region, whether Gwadar or Chabahar.

In our region, perhaps no country’s trade dynamics are as worth exploring as those with Afghanistan. After all, it is a landlocked country; if the old mantra of “geography is destiny” has some significance, it has to apply to Afghanistan. Afrasiab Khattak, a politician of a Pashtun nationalist party, argues that Afghanistan was once eminent for being at the heart of the Silk Road, connecting Asia and Europe, but became entangled in power politics after the rise of sea-borne trade. “That is when we see the rise of the Great Game between the British and Russian empires in the nineteenth century, all the way to the Cold War between the US and USSR in the twentieth century, with Afghanistan trapped in the middle,” argued Khattak.

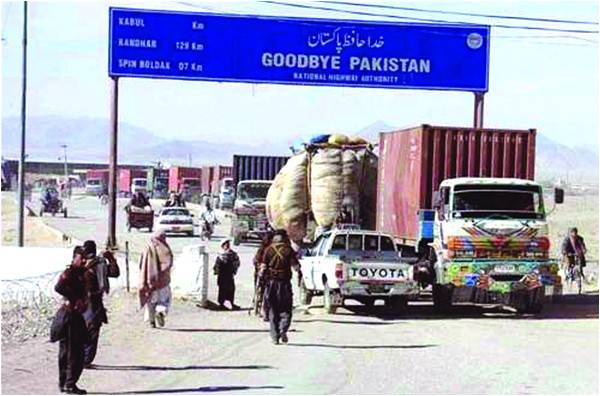

In more recent times, Afghanistan has to rely on one of its neighbours for direct as well as international trade. They include Pakistan and Iran to the south, and Central Asian countries to the north. Of these, lately, Pakistan’s Karachi port has been trusted as the key source of transportation of goods to and from Afghanistan.

Others routes had utility too. When in 1955, Pakistan closed its border with Afghanistan, it (Afghanistan) revisited its transit treaty with the Soviet Union. The exact trade from that side fluctuated, and at times was not even dominant, but the point that the option was there.

There have been limitations to other routes, especially after Afghanistan was plunged into conflict. The year 1979 was a fateful one when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, leading to a guerilla war. Those who fought against the Red Army should not have expected any supply of goods from the north. As for Iran, it had a revolution, gradually being isolated by the international community. Conducting business via Iranian ports would have been possible, but risky for many.

Three decades have passed. China is rising, seeking economic relations with countries in the region, including Afghanistan. In 2013, world powers reached a nuclear agreement with Iran, seeing renewed investment. India, which did not want to offend the western consensus, keenly followed suit by developing Chabahar port. More than once have we heard and read of Iran and India opening that port, which, among other things, will supply goods to Afghanistan. And supplied it has.

Shifting environment and trade

As trade from other avenues pick up, Pakistan’s volume dips in. One source estimated that the number of containers, which help measure commercial transit, has decreased to less than 50,000 from over 70,000 some years ago. More worrisome has been the decline of direct trade with Afghanistan: it stood at $1.2 billion in 2017. Even the peak of $2.7 billion touched in 2015 was less than the potential goal of $5 billion.

Admittedly, these figures are also contested, depending on who you ask. Importantly, one scholar questions the consistency of this decline, saying fluctuation is temporary. Pakistan-Afghanistan trade will always meet a certain threshold, goes the argument, given the shared consumption pattern between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Yet, for all the debates about the exact decline, the consensus is that there is decline here and incline towards Iran and a possibility of other countries joining in the future.

Also, if the past is any prologue, even though Afghanistan can shrug off Pakistan’s worries of trade shifting westwards, reliance on any single route is to be avoided too. If anything, the international community should help open routes for Afghanistan, so as not to make it anyone’s playfield in the future.

This clearly gives more room for the Afghan state to maneuver. Last November, Afghanistan’s chief Abdullah Abdullah shared at an American think-tank that, “Afghanistan used to rely on only one transit through Karachi. [But now there are] Chabahar and what is called the Lapis Lazuli corridor out through Azerbaijan to Europe.” The Lapis Lazuli corridor connects five countries all the way to Turkey via the Caspian Sea. A transit agreement with Uzbekistan was also discussed.

It means that any Afghan trader has multiple options. An Afghan trader, whose sole job is to sell certain goods in some parts of Afghanistan, after importing them, will now have multiple choices, Pakistan, Iran, and potentially northern ones too. Obviously, such a trader will check for the path which is less costly.

Distance alone cannot be taken as the determining factor. There are other payments too any trade has to make when transporting goods, besides the assurance that the goods will reach the destination in time. One should explore why it is that transportation via Karachi seems so prohibitive for traders that some are ready to opt for other routes.

From 2011 to 2013, trade had declined. It was blamed on a new transit trade agreement signed a year earlier, but three Peshawar-based academics disagree, saying other reasons are responsible: financial guarantees, port handling charges, transportation costs besides a lack of proper infrastructure. Authors of the paper blamed worsening relations after Salala for the decline.

Afghan traders suffer with the sudden shutdown of the border and even more so if they have “perishable” items. It is not hard to see which choices they will make. A small-scale trader is not concerned with geo-politics; he is concerned about the goods. If the trader realizes that he is losing money, he will have second thoughts too.

Pakistan has to work on an enabling environment. This may include managing the border to discourage any extra costs.

Impact on people and security

Bilateral and transit trade are linked, as traders or truckers can be the same. A report by the Royal Danish Defence College (RDC), based on a series of bilateral conferences it organized last year, in conjunction with the Regional Peace Institute, a Pakistani think-tank, says that, “by blocking transit trade, Pakistan is also decreasing the bilateral trade between Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

These trade networks contribute to the border economy, and even beyond that. Noreen Naseer of Peshawar University has written that that the primary economic source in the tribal areas of Pakistan (FATA) is agriculture, followed by trade. Even agricultural products have to make way through trade. The RDC report is clear: “Transit trade creates low-skill jobs in Pakistan, benefitting the poorest segments of Pakistani society.”

What is considered smuggling by people in the mainland is treated as business here. Afghanistan’s former deputy minister Mozamil Shinwari is paraphrased by the RDC report as saying: “For many people living in the border areas this unauthorized trade constitutes their primary source of income.”

With the shift of trade away from Pakistan, or a dip in bilateral trade, many people will be rendered jobless. Already, there are reports of businesses in Peshawar losing their clients because of the frequent border closures. Khattak warns of the “bad impact” of the closures.

These bordering areas have been most engulfed by militancy and insurgency. If any economic-militancy link exists here, it is about the lack of opportunities, or choices. Even Khattak, who would not discount the ideological undercurrents of some of the militant movements, warned: “An economic decline will boost Talibanization.”

The case is made more strongly in Afghanistan’s case. Mozammil Shinwari agreed in the RDC conference, saying, “some fight for economic reasons, as they do not have jobs or prospects outside the insurgency.” When it is said that there are some “reconcilable Taliban” who will be looped in, it is hoped the reference is towards those whose non-ideological motivations are stronger enough to be co-opted. And yet while enough time is wasted by trying to bring the “irreconcilable Taliban” around, there is no discussion on the reconcilable ones.

Pakistani border areas merit attention too. Cut off from the rest of the country administratively, FATA is also on the economic margins.

Back to (new) geopolitics?

In Pakistan, much of this potential trade shift is seen only in geo-strategic signs. Commentaries run high on how certain countries are intent on sabotaging us. Why not, for instance, lay the ground for a route that attracts traders to transport through Pakistan? If there is one geo-strategic change that matters, it is about the entry of China. Their argument has been economic uplift and connectivity. Afrasiab Khattak reasons that our policy planner’s approach of viewing everything in the context of zero-sum reek of a Cold War mentality, which is dissimilar to what the Chinese have been saying.

To the Chinese, it is no big deal if Chabahar or any other port is built. It can be complementary to Gwadar, a view reckoned by Iran too. And Islamabad is realizing that too; last year, when the first phase of Chabahar port was being inaugurated, Pakistan’s minister of ports and shipping also participated.

Gwadar port will be managed by the Chinese for some time; the port’s attraction for Afghanistan will be much in their hands too. Pakistan would be better off working towards a friendly trade environment. The opening of Ghulam Khan Pass in North Waziristan is a step in the right direction.

Admittedly, China has security concerns from this part of the world too. But instead of taking a more direct security role for a while, even in Afghanistan, they would like to take an economic initiative, which directly contributes to security.

In late December 2017, the Chinese foreign minister, after a meeting with the Pakistani and Afghan foreign ministers, was reported by China Daily as saying that “one of the first options could be improving livelihoods at border areas.”

The exact implementation is yet awaited, but the statement should not be ignored. One way is to go about integrating that part in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Part of this is already provided in the western corridor. Many contest if it has been accorded priority. It seems to have both domestic and regional significance.

If properly achieved, this could even help with the economic mainstreaming of areas like FATA. Earlier on the Chinese and the Americans had also talked about shaping Reconstruction Opportunity Zones in the area, to create jobs, but nothing came of it. Will the Chinese succeed where the Americans couldn’t?

One aspect of this bilateral relation that is overlooked is Pakistan’s trade with Afghanistan. As the world or this region moves towards geo-economics, as the oft-stated phrase goes, the volume of one country’s trade with another will be a moot point. We can see what is happening when we come across partially heated debates on the ports being developed in the region, whether Gwadar or Chabahar.

In our region, perhaps no country’s trade dynamics are as worth exploring as those with Afghanistan. After all, it is a landlocked country; if the old mantra of “geography is destiny” has some significance, it has to apply to Afghanistan. Afrasiab Khattak, a politician of a Pashtun nationalist party, argues that Afghanistan was once eminent for being at the heart of the Silk Road, connecting Asia and Europe, but became entangled in power politics after the rise of sea-borne trade. “That is when we see the rise of the Great Game between the British and Russian empires in the nineteenth century, all the way to the Cold War between the US and USSR in the twentieth century, with Afghanistan trapped in the middle,” argued Khattak.

Why it is that transportation via Karachi seems so prohibitive for those traders that some of them are ready to opt for other routes

In more recent times, Afghanistan has to rely on one of its neighbours for direct as well as international trade. They include Pakistan and Iran to the south, and Central Asian countries to the north. Of these, lately, Pakistan’s Karachi port has been trusted as the key source of transportation of goods to and from Afghanistan.

Others routes had utility too. When in 1955, Pakistan closed its border with Afghanistan, it (Afghanistan) revisited its transit treaty with the Soviet Union. The exact trade from that side fluctuated, and at times was not even dominant, but the point that the option was there.

There have been limitations to other routes, especially after Afghanistan was plunged into conflict. The year 1979 was a fateful one when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, leading to a guerilla war. Those who fought against the Red Army should not have expected any supply of goods from the north. As for Iran, it had a revolution, gradually being isolated by the international community. Conducting business via Iranian ports would have been possible, but risky for many.

Three decades have passed. China is rising, seeking economic relations with countries in the region, including Afghanistan. In 2013, world powers reached a nuclear agreement with Iran, seeing renewed investment. India, which did not want to offend the western consensus, keenly followed suit by developing Chabahar port. More than once have we heard and read of Iran and India opening that port, which, among other things, will supply goods to Afghanistan. And supplied it has.

Shifting environment and trade

As trade from other avenues pick up, Pakistan’s volume dips in. One source estimated that the number of containers, which help measure commercial transit, has decreased to less than 50,000 from over 70,000 some years ago. More worrisome has been the decline of direct trade with Afghanistan: it stood at $1.2 billion in 2017. Even the peak of $2.7 billion touched in 2015 was less than the potential goal of $5 billion.

Admittedly, these figures are also contested, depending on who you ask. Importantly, one scholar questions the consistency of this decline, saying fluctuation is temporary. Pakistan-Afghanistan trade will always meet a certain threshold, goes the argument, given the shared consumption pattern between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Yet, for all the debates about the exact decline, the consensus is that there is decline here and incline towards Iran and a possibility of other countries joining in the future.

When in 1955, Pakistan closed its border with Afghanistan, it (Afghanistan) revisited

its transit treaty with the Soviet Union

Also, if the past is any prologue, even though Afghanistan can shrug off Pakistan’s worries of trade shifting westwards, reliance on any single route is to be avoided too. If anything, the international community should help open routes for Afghanistan, so as not to make it anyone’s playfield in the future.

This clearly gives more room for the Afghan state to maneuver. Last November, Afghanistan’s chief Abdullah Abdullah shared at an American think-tank that, “Afghanistan used to rely on only one transit through Karachi. [But now there are] Chabahar and what is called the Lapis Lazuli corridor out through Azerbaijan to Europe.” The Lapis Lazuli corridor connects five countries all the way to Turkey via the Caspian Sea. A transit agreement with Uzbekistan was also discussed.

It means that any Afghan trader has multiple options. An Afghan trader, whose sole job is to sell certain goods in some parts of Afghanistan, after importing them, will now have multiple choices, Pakistan, Iran, and potentially northern ones too. Obviously, such a trader will check for the path which is less costly.

Distance alone cannot be taken as the determining factor. There are other payments too any trade has to make when transporting goods, besides the assurance that the goods will reach the destination in time. One should explore why it is that transportation via Karachi seems so prohibitive for traders that some are ready to opt for other routes.

From 2011 to 2013, trade had declined. It was blamed on a new transit trade agreement signed a year earlier, but three Peshawar-based academics disagree, saying other reasons are responsible: financial guarantees, port handling charges, transportation costs besides a lack of proper infrastructure. Authors of the paper blamed worsening relations after Salala for the decline.

Afghan traders suffer with the sudden shutdown of the border and even more so if they have “perishable” items. It is not hard to see which choices they will make. A small-scale trader is not concerned with geo-politics; he is concerned about the goods. If the trader realizes that he is losing money, he will have second thoughts too.

Pakistan has to work on an enabling environment. This may include managing the border to discourage any extra costs.

Impact on people and security

Bilateral and transit trade are linked, as traders or truckers can be the same. A report by the Royal Danish Defence College (RDC), based on a series of bilateral conferences it organized last year, in conjunction with the Regional Peace Institute, a Pakistani think-tank, says that, “by blocking transit trade, Pakistan is also decreasing the bilateral trade between Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

These trade networks contribute to the border economy, and even beyond that. Noreen Naseer of Peshawar University has written that that the primary economic source in the tribal areas of Pakistan (FATA) is agriculture, followed by trade. Even agricultural products have to make way through trade. The RDC report is clear: “Transit trade creates low-skill jobs in Pakistan, benefitting the poorest segments of Pakistani society.”

What is considered smuggling by people in the mainland is treated as business here. Afghanistan’s former deputy minister Mozamil Shinwari is paraphrased by the RDC report as saying: “For many people living in the border areas this unauthorized trade constitutes their primary source of income.”

With the shift of trade away from Pakistan, or a dip in bilateral trade, many people will be rendered jobless. Already, there are reports of businesses in Peshawar losing their clients because of the frequent border closures. Khattak warns of the “bad impact” of the closures.

These bordering areas have been most engulfed by militancy and insurgency. If any economic-militancy link exists here, it is about the lack of opportunities, or choices. Even Khattak, who would not discount the ideological undercurrents of some of the militant movements, warned: “An economic decline will boost Talibanization.”

The case is made more strongly in Afghanistan’s case. Mozammil Shinwari agreed in the RDC conference, saying, “some fight for economic reasons, as they do not have jobs or prospects outside the insurgency.” When it is said that there are some “reconcilable Taliban” who will be looped in, it is hoped the reference is towards those whose non-ideological motivations are stronger enough to be co-opted. And yet while enough time is wasted by trying to bring the “irreconcilable Taliban” around, there is no discussion on the reconcilable ones.

Pakistani border areas merit attention too. Cut off from the rest of the country administratively, FATA is also on the economic margins.

Back to (new) geopolitics?

In Pakistan, much of this potential trade shift is seen only in geo-strategic signs. Commentaries run high on how certain countries are intent on sabotaging us. Why not, for instance, lay the ground for a route that attracts traders to transport through Pakistan? If there is one geo-strategic change that matters, it is about the entry of China. Their argument has been economic uplift and connectivity. Afrasiab Khattak reasons that our policy planner’s approach of viewing everything in the context of zero-sum reek of a Cold War mentality, which is dissimilar to what the Chinese have been saying.

To the Chinese, it is no big deal if Chabahar or any other port is built. It can be complementary to Gwadar, a view reckoned by Iran too. And Islamabad is realizing that too; last year, when the first phase of Chabahar port was being inaugurated, Pakistan’s minister of ports and shipping also participated.

Gwadar port will be managed by the Chinese for some time; the port’s attraction for Afghanistan will be much in their hands too. Pakistan would be better off working towards a friendly trade environment. The opening of Ghulam Khan Pass in North Waziristan is a step in the right direction.

Admittedly, China has security concerns from this part of the world too. But instead of taking a more direct security role for a while, even in Afghanistan, they would like to take an economic initiative, which directly contributes to security.

In late December 2017, the Chinese foreign minister, after a meeting with the Pakistani and Afghan foreign ministers, was reported by China Daily as saying that “one of the first options could be improving livelihoods at border areas.”

The exact implementation is yet awaited, but the statement should not be ignored. One way is to go about integrating that part in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Part of this is already provided in the western corridor. Many contest if it has been accorded priority. It seems to have both domestic and regional significance.

If properly achieved, this could even help with the economic mainstreaming of areas like FATA. Earlier on the Chinese and the Americans had also talked about shaping Reconstruction Opportunity Zones in the area, to create jobs, but nothing came of it. Will the Chinese succeed where the Americans couldn’t?