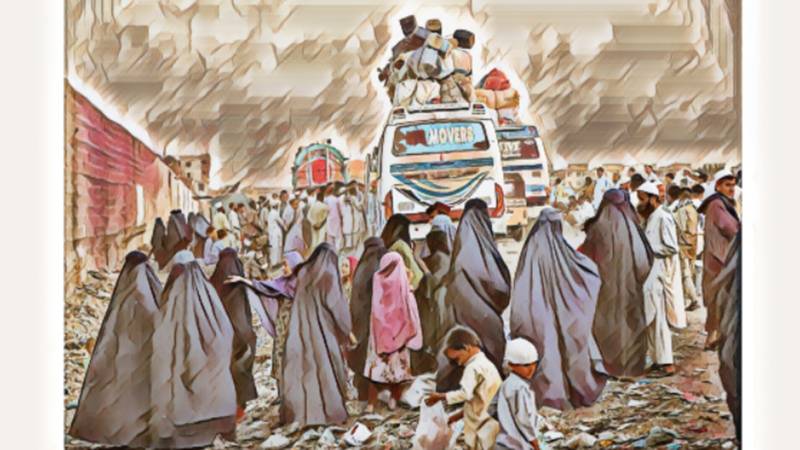

Afghan Hazaras are grappling with the enduring impact of war, conflict, and loss. They are apprehensive about a potential worsening of their lives in a religiously ruled Afghanistan where patriarchy and tribal conflicts compound the exploitation, suppression, and violence they face.

In Quetta, Afghan Hazaras, particularly the Shia Muslim minority, confront trauma. Their religious beliefs mark them out as vulnerable, alongside tribal feuds and patriarchy, rendering them at risk if they return to Afghanistan. Economic vulnerability, stemming from a lack of justice, land, and housing, combines with the fear of terrorist attacks in their homeland. Millions of Afghans sought refuge in neighboring Pakistan and Iran since the Soviet-backed Saur revolution, and there has been another wave of refugees after the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan.

Seema Gull, a Hazara Shia Muslim, fled to Pakistan in 2021, registering her case with UNHCR in Quetta. With her community facing the threat of the terror group Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP), her plight includes tribal feuds over agricultural land, leaving her wounded and traumatised.

Her narrative reflects the constant threat faced by her community in Kabul under the Taliban regime, known for its strict interpretation of Sharia that bars women from jobs and halts girls' education. Fleeing the turmoil, Seema sought refuge in Quetta. And she is now concerned about the Pakistani government's policy to repatriate 1.7 million registered and unregistered Afghan refugees.

Living in a private school building as a class-IV employee in exchange for shelter, Seema reveals her head injury and mental health struggles, as well as her treatment by a psychiatrist. Despite lacking formal education, she resisted the feudal norms in her home district, highlighting the impossibility of justice through Afghanistan's state structure, where those in power align with the wealthy.

Seema recounts her traumatic experience: "My husband is economically weaker, considered prey by the powerful. His cousin sought to seize our ancestral land, but I resisted; he hit my head with a shovel." In patriarchal systems, female defense of family land is deemed abnormal, a sentiment evident in Seema's struggle. Her plea for justice echoes the systemic failures: "Governments offer no justice; under the Taliban, we fear terrorist attacks, yet the Pakistani government forces us to return."

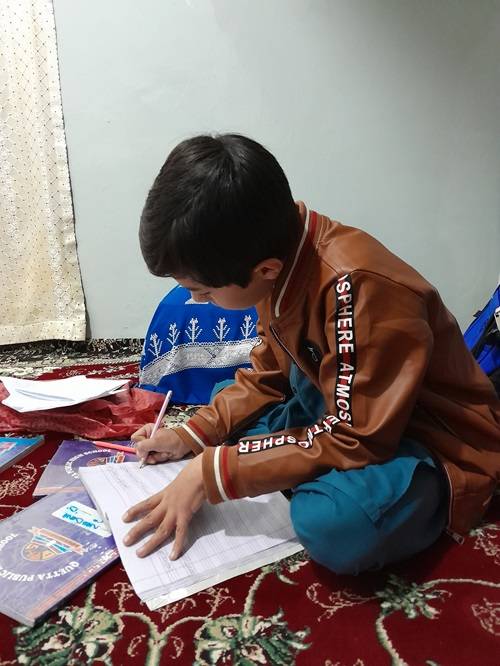

Millions of refugee children born in Pakistan face an uncertain future. Manzoor, a first-grade student born in Quetta, is afraid to go for his tuition classes in Mariabad, as his parents are in hiding like so many others due to the Pakistani government rounding up thousands like them. When approached by a reporter, Manzoor was adorned in a mock Pakistan Army uniform, emphatically asserting his Pakistani identity: “I am a Pakistani, look, I have a flag on my chest and the uniform.” Despite this, Manzoor cannot possibly begin to understand the views of citizenship, laws, and state policy that pose a risk to his family in their adopted country.

Manzoor's mother, Shehnaz, hails from Afghanistan, having arrived in Pakistan at the age of 8. In a telephone interview, she lamented her lack of prospects, acknowledging that her current life in Pakistan is suboptimal but markedly superior to the conditions in Afghanistan. She expressed concern for her children's future, fearing the denial of education for her four offspring and the absence of employment opportunities for her husband. Reflecting on her own predicament, Shehnaz remarked, "I have attended Afghan schools in Pakistan, my four children were born here, and I fear for them. However, what deeply troubles me is the outlook for my children's education in Afghanistan, where girls are barred from receiving education, and the economic crisis prevents even our male children from attending schools."

Pakistan has the capacity to reassess the forcible repatriation of Afghan refugees facing danger in their homeland, with a particular emphasis on women, journalists, and former employees of INGOs. Those associated with the former Afghan Republic constantly contend with threats. The de-facto Taliban government remains unrecognised, and a media blackout has heightened apprehensions, especially among those with religious beliefs conflicting with the Taliban's interpretation of Sharia.

"Violence against women and girls existed during the days of the Afghan Republic as well because third-world countries harbour patriarchal cultures. Now, with women barred from jobs and education under the Taliban, the situation has become even more perilous for minorities. The Government of Pakistan should reconsider its policy regarding the persecution of women and religious minority groups in their homeland," asserts Dr. Shahida Habib Alizai, Assistant Professor at the Department of Gender Development Studies at the University of Balochistan.

Human rights activist Jalila Hazara believes that the majority of Afghans live in a society where job opportunities are minimal, and they are perpetually under the control of minority elites and religious leaders. These power structures subject people to patriarchy and exploitation, and Hazaras face these issues internally as well.

"These Afghan people were brought into camps by both Pakistan and Iran to bolster the anti-Soviet war. Even Hazara warlords joined the war in Afghanistan. Hazaras live in tribes, facing religious extremism externally, yet they themselves grapple with tribal divisions. The forced repatriation of impoverished Hazaras who have lived in Pakistan would undoubtedly lead to a humanitarian catastrophe, subjecting women and girls to patriarchy," warns Jalila.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees expresses concern about the forced repatriation of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, urging Pakistani authorities for voluntary, safe, and dignified repatriation while safeguarding those requiring international protection.

"The ongoing pressure to return has caused severe distress within communities, despite assurances from the Government of Pakistan," states Philippa Candler, UNHCR Representative in Pakistan, during a press briefing. "We reiterate our call for voluntary, safe, and dignified returns, irrespective of legal status in Pakistan. We urge the Government of Pakistan to implement a screening mechanism to identify individuals in need of international protection. UNHCR is offering support to Pakistan to establish a system addressing both the legitimate concerns of the government and the safety of Afghans seeking refuge on its territory."

Seema, clutching her medical report and UNHCR case documents due to fear of persecution in Afghanistan, turns pale and says, "We are human; we deserve a life. Forced repatriation would mean being thrown into death and deprivation forever in a country where ISKP, the de-facto Taliban government, and our tribal rivals pose continuous threats."