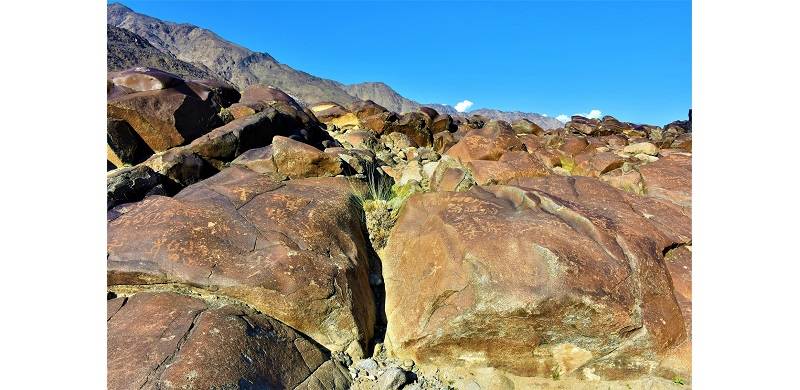

Traveling on the Karakorum Highway (KKH) opens a number of historical vistas for anyone undertaking that journey. On the way from Shatial to Gilgit, one spots many engraved boulders and cliffs. There are many rock art sites located on both banks of the Indus River. Right from Shatial in upper Kohistan district of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province (KP) to Sost in Upper Hunza, the talking rocks tell many stories about the religion and economy of bygone communities. On both the right and left banks of the Indus river are located many rock art sites. Prominent among these are Manro Das, Kino Kor, Bazeri Das, Minar Gah, Thor North, Helor Das, Oshibat, Hodur, Dadam Das, Chilas, Thalpan, Thak, Gichi, Shing, Partab Bridge and Alam Bridge. In Gilgit town, there are also located two main rock art sites including Danyor, Kuno Das and the famous rock relief of Karga Buddha. A majority of these sites have been studied by German and Pakistani scholars.

Not much has been written on the rock carvings and inscriptions of Minar Gah. A catalogue of inscriptions of Minar Gah is published as an appendix to Materialien Zur Archäologie der Nordgebiete Pakistan (MANP) Vol.9 by the Heidelberg Academy for Humanities and Sciences. There are only photographs of inscriptions and nothing is discussed about the rock carvings that are found at Minar Gah. There is only a passing remark on two of the ibex images in the book Between Gandhara and the Silk Roads: Rock Carvings along the Karakorum Highway coauthored by Prof. Dr Karl Jettmar and Dr. V. Thewalt (1987). According to them, two ibex images were made in the 4th century BC or later.

The Minar Gah rock art site is located on the left bank of the Indus River in the Diamer district. It is about 30 km west of Chilas town. Many small boulders are covered with rock carvings and Brahmi inscriptions. Both prehistoric and historic rock carvings are found at Minar Gah. Prehistoric rock carvings are mainly located near the riverbank whereas the historic images are mainly concentrated at the roadside. There are animal, human, geometric and religious motifs that are engraved on the boulders at Minar Gah. Some unidentified carvings are also found at this site.

There are about 89 Brahmi inscriptions at Minar Gah which were written by pilgrims, travellers, traders and others – mainly in the 4th and 5th centuries. The majority of the boulders depict animals, hunters, warriors, stupas, tridents, the sun motif, the linga and dancing scenes.

The dancing scenes are most interesting in the rock art of the Diamer district. Although there are quite a few rock art sites in Diamer where one finds dancing scenes, the topic has not yet attracted scholarly attention for people to separately focus on this theme in rock art.

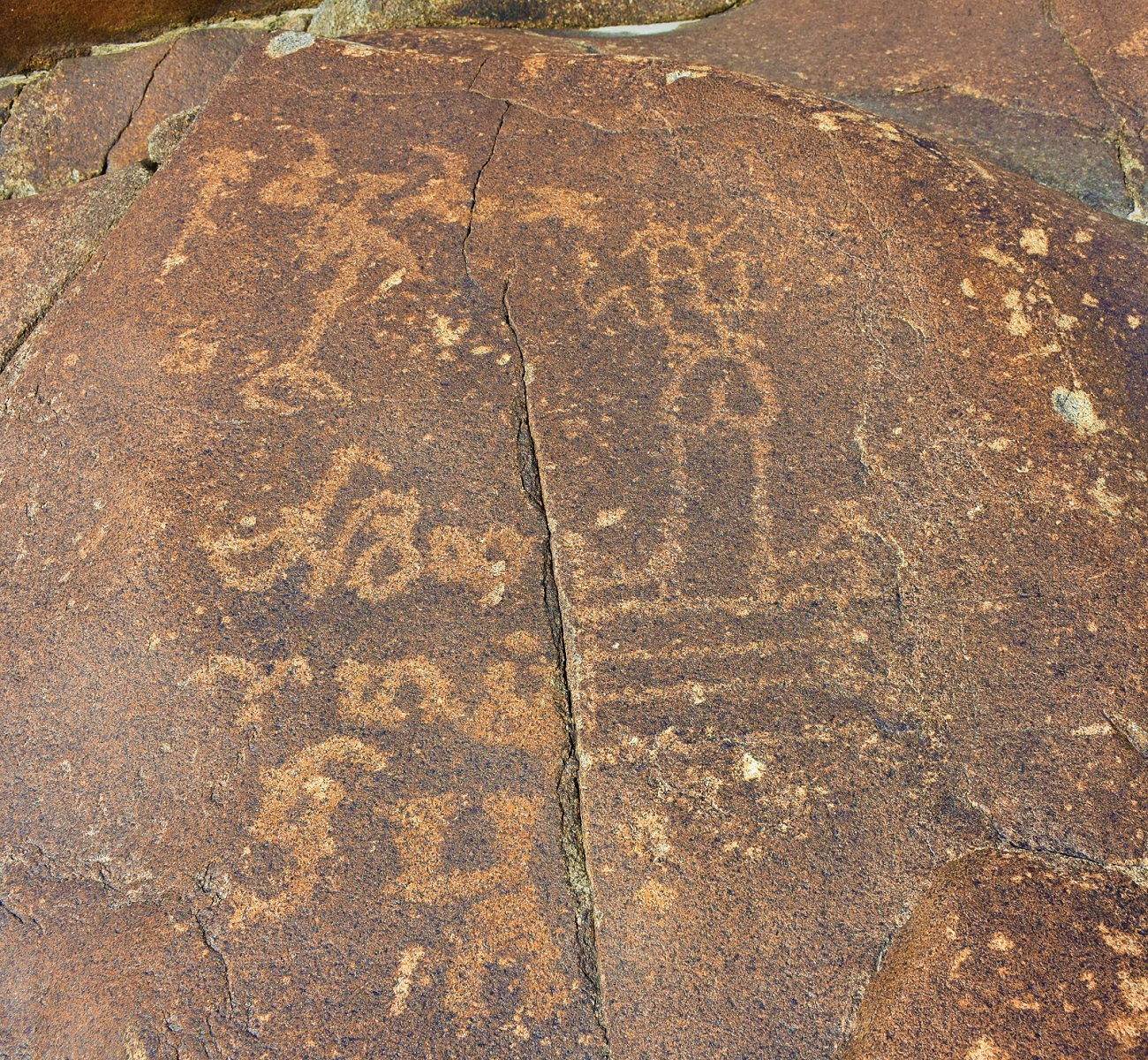

There is a row of dancers at Minar Gah who are shown holding hands with each other. They are depicted dancing before a verandah-like structure. This appears to be a ritual dance. Now ritual dance scenes are a recurrent theme in the rock art of Gaj valley in Sindh. I have also discussed a similar type of ritual dance before a verandah-like structure at Chiti rock art site in Gaj valley in Sindh in my book Symbols in Stone: The Rock Art of Sindh published in 2018 by the Endowment Fund Trust for Preservation of the Heritage of Sindh. I have documented depictions of dancers before a bull at a few rock art sites in Sindh. In fact, I have also seen this theme painted in rock shelters of Pallimas near Wadh in Khuzdar district. At Pallimas, the dancers are shown in a row dancing before the bull – a scene which probably shows the celebration connected to the domestication of the bull.

I have also seen dancing scenes at the rock art site of Thor North, which is not far from the rock art site of Minar Gah. The representation of gift bearers and dancers before a deity – or King Maues as interpreted by Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani – is probably a dancing scene engraved at the Chilas II rock art site. I will discuss this narrative and dancing scene in a separate article. There is a row of seven dancers at the Ziarat rock art site II in Thalpan, which was interpreted by Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani as men carrying a raft. This is actually a ritual dance for a hunt. Before the dancers is depicted a hunter shooting at a markhor.

Human figures are shown hunting, dancing and fighting. Two warriors are engraved on a boulder: both are wielding battle axes and shields. One of the warriors is seated on horseback and the other on foot

Apart from the dancing scene, the most noticeable carving at Minar Gah is of a linga. The linga, an aniconic representation of Hindu god Shiva, is depicted on a stand with two Brahmi inscriptions on its left. It is also interesting to note that there are quite a few linga representations at the rock art sites of the Diamer district. Apart from the Minar Gah linga representation, one can also see an engraving of the linga at the Manro Das rock art site. This Manro Das or Asmidesa rock art site is located opposite Minar Gah on the right bank of the Indus. A linga is also engraved at the Thor North rock art site.

Apart from the Diamer district, linga images are mostly seen at the Shatial rock art site in the upper Kohistan district in KP. This rock art site depicts more of the linga or phallus than any other rock art site in the upper Indus valley. This probably shows the linga cult or phallus worship which was prevalent in the upper Indus valley in ancient times. It is difficult to say when the linga cult began in this region. However, on the linga cult in India Atul K. Sur writes in the article Beginning of Linga Cult in India published in Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute in 1931-32 that according to available data, the date of the cult in India could not be pushed back beyond the Imperial Gupta period. This means that the linga cult in the present Upper Indus valley was probably prevalent between the 3rd to 5th centuries AD. These engravings were likely made during that period. Moreover, later when the linga cult began to wane, new images of linga caricatures appeared on the rocks of Shatial, in which a monkey with the upper part of the body was formed into a phallus. I believe that earlier phallic representations were shown on a stand whereas the later depictions, which appeared probably in the 7th or 8th centuries – or maybe later – were made without a stand or yoni.

The representation of standing Shiva and his bust are also found in rock art sites of Thalpan and Dadam Das respectively. This is good evidence to argue that Shiva worship - both of his image and in his aniconic representation - was prevalent in the upper Indus valley in ancient times.

Besides dancing scenes and linga depictions, there are several representations of animals at Minar Gah. Amongst the animals, the images of ibex are more numerous. One of the boulders shows the most interesting carvings of two ibexes which are depicted approaching water bodies. Representations of water bodies are also carved before both the animals. There are also man and snake depictions on the same boulder.

Human figures are shown hunting, dancing and fighting. Two warriors are engraved on a boulder: both are wielding battle axes and shields. One of the warriors is seated on horseback and the other on foot.

Buddhist symbols are also numerous at this site, which are mainly represented by stupas. Two tridents, representing either the trisula attribute of Shiva or the triratna/mangla of Buddhists are engraved on two separate boulders. There is also a carving of a swastika on one of the boulders at the Minar Gah rock art site. A handprint is also engraved on a boulder at Minar Gah. In fact, handprints are also found in many rock art sites all along the Indus river – right from Shatial to Shing Nala.

The author is an anthropologist. He may be contacted at zulfi04@hotmail.com. Excerpts have been taken from the author’s forthcoming book Cultural Heritage Along the Silk Road in Pakistan. All photos by the author